I confess that when I first encountered Edward Burra’s vibrant paintings of African-Americans languidly hanging out on the streets and in the the jazz clubs of Prohibition New York I assumed that Burra was black – a member of the Harlem Renaissance, perhaps.

I couldn’t have been more wrong, as I later discovered. Burra was a white Englishman, the son of a rich lawyer who never needed to earn his living. Born in 1905, he had a dull, comfortable upbringing in Rye, and led a particularly closeted life since he had been crippled by a rare form of arthritis from an early age. The family lived in a handsome and substantial mansion with eight servants and 11 acres of garden.

and led a particularly closeted life since he had been crippled by a rare form of arthritis from an early age. The family lived in a handsome and substantial mansion with eight servants and 11 acres of garden.

Back in October on BBC 4, Andrew Graham-Dixon presented an excellent film on Edward Burra – ‘the most intriguing 20th century artist you might never have heard of’ in his words. The film coincided with the first major retrospective of Burra’s work for 25 years at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. Since I’m unlikely to get to Chichester before the exhibition closes, this post is by way of an appreciation of an artist whose work I have loved since I first encountered his paintings of Harlem night life. Andrew Graham-Dixon’s film revealed to me aspects of Burra’s work of which I was unaware – most especially, the beautiful watercolours of English landscapes which he produced in the post-war years.

The unpromising elements of his early life were probably the key to Burra’s artistic trajectory – in the sense that he became determined to overcome the constraints of his class and physical condition through art, travel, music and the night life. By the age of 15 Burra was off to art school in London. From there, over the next few decades, he travelled incessantly: to art hotspots such as Paris in the 1920s, Harlem in the 1930s and Spain during the Spanish Civil War.

There’s an early painting, In The Tea Shop (1929), in which Burra pokes fun at his home town. In it, the prim local matrons are served by nubile waitresses, naked except for a tiny pinafore. The waitress in the foreground appears to be pouring coffee on the cloche hat of a lady customer, pop-eyed with shock. Men in bowler hats look on in astonishment or hide behind their newspapers. Marriage a la modepainted a year earlier, as well as being a homage to Hogarth, is reminiscent of Stanley Spencer in its modelling and the intermingling of the earthly and the divine – and also seems to suggest a satirical slant on local mores.

Another early painting inspired by a metropolitan rather than provincial setting isThe Snack Bar (1930). It’s an odd affair: a woman whose thoughts are elsewhere is frozen in the act of placing a sandwich between her brightly-painted lips, while the man behind the counter suggestively slices an enlarged salami while glancing in her direction.

Burra’s biographer Jane Stevenson has written of this painting:

Two of his friends, in interview, pinpointed both the subject and the place: “Soho tarts were mostly French around 1930 and dressed and made up just like that.” The venue is the Continental Snack Bar in Shaftesbury Avenue, which “was very handy for ladies on the game to have a sit down and a cup of tea in their rest periods”. This image of a working girl stuffing food into her mouth is an extremely unusual approach to the representation of the female body in its time. Women, particularly prostitutes, were persistently eroticised, reified or abstracted in the art and imagery of the period. Burra enjoyed the rhetoric of “sin flaunting with a painted grin”, but that is not what he represents in this picture. Eliot’s typist could be slumped on the next stool, slurping tea and bolting a quick snack before returning to her afternoon’s stint in the office. Though he seems never to have been sexually attracted to women, Burra was more aware of them as people than most artists of his time, and less scared of them, for the simple reason that he shared his home life with his mother, two sisters and a nanny, all of whom he liked and understood.

In early paintings like this Burra comes across as a caricaturist and satirist in the style of Otto Dix or George Grosz, capturing and exaggerating every telling detail of the eccentric, bustling crowds in the cafés and nightclubs he frequented with the close friends he hade made at art school. The 1920s were, Burra observed, a time of great frivolity and fun – ‘we spent much of our time going to the cinema and reading Vogue magazine’.

That Burra relished travel and city nightlife is remarkable given that, as a result of his disability, he was subject to regular collapses (eventually diagnosed as being the result of a disease of the red blood cells) which meant that invariably ‘his basic state of being was akin to a machine operating on a nearly flat battery’ (Jane Stevenson). His lifelong struggle with rheumatoid arthritis and the debilitating blood disease meant that he was never able to use an easel in the conventional way. Instead he opted to sit, working mostly in unfashionable watercolour on thick paper laid flat on a table. But he created watercolours like no others: idiosyncratic images teeming with the men and women who fascinated him: bohemians, sailors, prostitutes, lowlifes – those who live by night. George Melly, a close friend, once expressed his wonder at the way that Burra’s crippled hand became ‘an unlikely instrument of so much precise beauty’.

Andrew Graham-Dixon’s film traced Burra’s life, from his native town of Rye to the jazz clubs of Prohibition New York, then to the battered landscapes of the Spanish Civil War and back to England during the Blitz. Graham-Dixon argued that Burra’s work deepened and matured as he experienced at first hand some of the most tragic events of the 20th century. He painted a fascinating portrait of Burra – a master of the camp, throwaway phrase, who preferred to create art rather than talk about it, and who responded to most queries about his work with an ‘Oh Dearie, I never tell anyone anything…’ (thereby providing the title for the film).

Simon Martin, the curator of the Pallant House exhibition, writes that although born into a solidly middle-class family,

Burra was always attracted to the less salubrious side of society. While some artists spend their careers trying to achieve a respectable social position, it seems that he spent years trying to escape from his. It is typical of Burra that when given money by his mother to treat his enlarged spleen he spent it instead on getting a tattoo of a fearsome Chinese mask on his left shoulder. Despite suffering from crippling arthritis throughout his life, he had a tenacious will, and often went on cosmopolitan excursions; his experience led him to produce some of the most remarkable watercolours by any British artist in the 2oth century.

The cinema remained a great love – and source of inspiration – throughout his life. As Graham-Dixon pointed out, Burra’s sense of composition – with extreme close-ups, plunging, vertiginous perspectives, close cropping and heavily made-up faces with exaggerated expressions – was derived from the old silent movies. Burra’s biographer, Jane Stevenson, suggests that rather like the novelist Christopher Isherwood, Burra was a ‘camera’ – a spectator with an extraordinary memory for vivid detail.

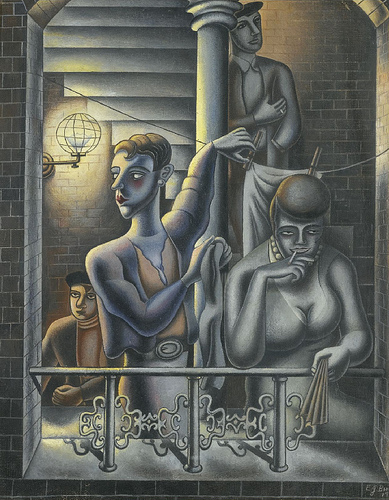

Burra was fascinated by modern urban life, whether dockside bars in Toulon or Marseille, or jazz dives and nightclubs in Harlem or Boston. He was British, yet, except for some Second World war paintings the evocative English landscapes of the post-war period, much of his work did not deal with Britain at all. Burra was fascinated by the cheap glamour of dancers and prostitutes, in Mediterranean seaports or the boulevards of Montparnasse. Though it seems certain that Burra’s sensibility was gay, he never took a lover according to biographer Jane Stevenson, and it’s unlikely that he had any first-hand experience of brothels. Scenes such as the prostitutes depicted in The Common Stair (1929) hanging up their garments to dry on a communal staircase were a combination of his memories of life on the streets of Toulon or Marseilles and elements drawn from the movies that he watched avidly: ‘ the picture is unmistakably Burra – a fusion of his ability to draw together disparate influences into his own distinctive world view’.

Burra embraced the unrespectable: scantily-clad nightclub performers, transvestites, sailors in search of a pick-up, tarts in a snack bar. Simon Martin writes:

He expressed a ‘gay’ sensibility at a time when such personal honesty and an overtly camp aesthetic were by no means widely acceptable. Decades before Grayson Perry explored transvestism in his art, Burra depicted men in drag and in his hilarious letters adopted the alter egos of ‘Lady Bureaux’ and ‘Madame Mata-Hari’. He was not interested in what other people thought of him, but he was interested in people, in their foibles and eccentricities, and in the dark side of humanity.

Crowded urban scenes first began to appear in Burra’s paintings in the late 192os, partly reflecting his love of cinema and his admiration for contemporary French poets such as Jules Romains, whose imagery was drawn from the streets and dance halls. Market Day (1926) is a busy port scene with two black sailors on shore leave carrying their ditty bags and being accosted by hip-jutting prostitutes. Burra’s attention to detail ranges from the tonally matching jacket and tie worn by the sailor on the left, to the bowl of fruit carried on a woman’s head like a still life at the centre of the composition.

Simon Martin continues:

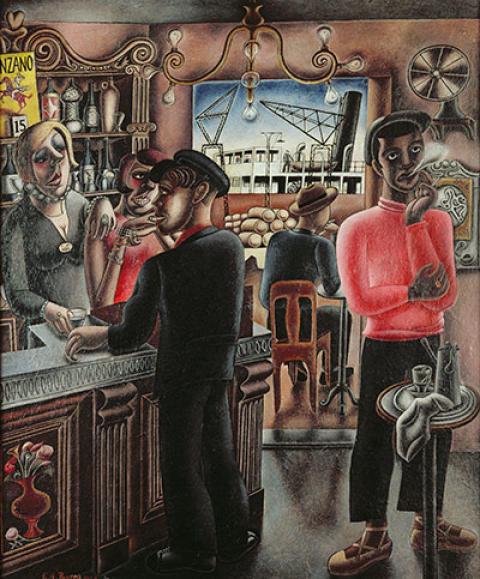

Burra’s Dockside Cafe Marseilles (1929) is a study in the coded language of sexual ambiguity, employing high camp and innuendo. Although the cinematic view of cranes and the upper deck of a boat confirm the waterfront location, the characters within are not the macho sailors or dockworkers one might expect. Instead young man with his cap at a rakish angle, bejewelled ring and seemingly plucked eyebrows stands at the bar. The two barmaids have the exaggerated appearance of men in drag, while the body language of the black youth in a pink sweater, cropped trousers and ballet shoes who stands smoking to the right of the image suggests that this is a covert place for gay men to meet.

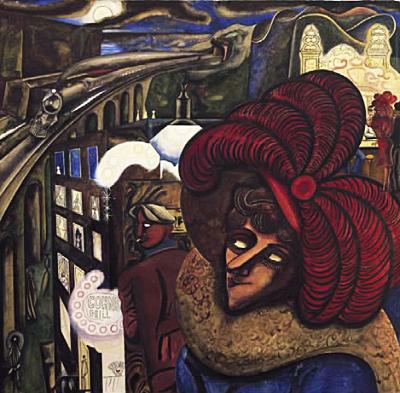

Izzy Orts depicts a popular bar and dance-hall once located at the docks in Boston. On visits to the city to stay with his friend, the writer Conrad Aiken, Burra was a frequent visitor to the bar, perhaps attracted by its lively and diverse clientele. Burra visited America several times and this picture is believed to have been painted during his second visit in 1937. The vibrant scene contains a number of strange characters, such as the disquieting blank-eyed sailor who faces the viewer. The sailor in the foreground on the left is a self-portrait of the artist.

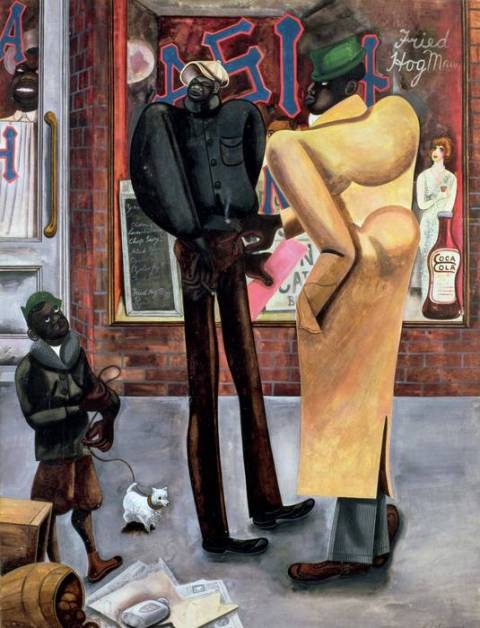

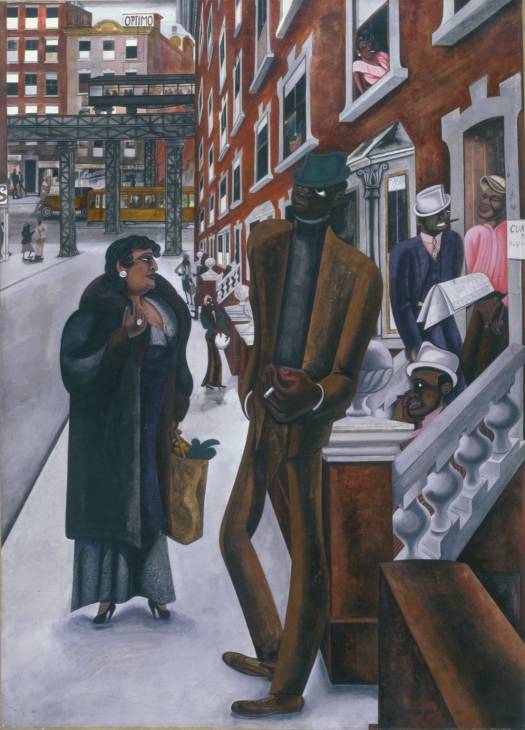

Edward Burra’s paintings of Harlem fall into two groups – street scenes and scenes of night-time entertainment. This painting, Harlem, depicts the area’s daytime street life. Several men and women are shown in front of a row of brownstone tenements, with New York’s elevated railway visible in the background. The street is shown as a place of social interaction: people linger on their doorsteps to smoke, talk and read newspapers. In contrast to the glamour and exuberance of Harlem nightlife, this painting presents a more downbeat scene of uncertain, possibly illicit, employment.

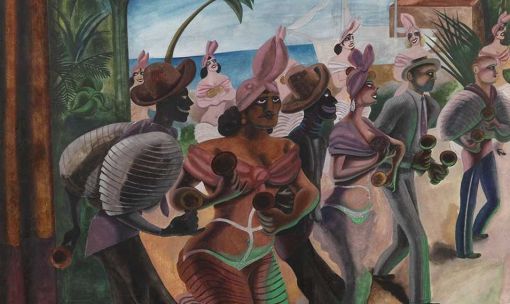

Burra adored the glittering spectacles of dancing revues at the Folies-Bergere, in particular the African-American dancer and jazz singer Josephine Baker. But whilst many modern artists conflated Baker and the Revue negre with the ‘primitivism’ of African tribal sculpture, Simon Martin argues that Burra’s appreciation seems to have been rooted in a genuine love of modern black jazz music and visual culture, with no suggestion of any ‘primitivising’ tendency in his work. Indeed, Burra depicted a multi cultural society that has few parallels in the work of other artists. Martin continues:

At a time of widespread racist imagery in the media, his pictures were conspicuous for their lack of prejudice and genuine warmth towards black people. The series of paintings inspired by street life in Harlem that he did following visits to New York in 1933 and 1934 stands out as a major contribution to the history of black visual representation and deserves to be seen in the context of the African-American cultural movement known as the Harlem Renaissance. With apparent warmth, they capture a sense of nonchalance: women smoking out of the window of apartment blocks, groups lingering on the steps, and men idling on street corners with their prohibition liquor in paper bags. These, and later images of Boston nightlife such asSilver Dollar Bar (1953),led the poet Conrad Aiken to describe Burra as ‘the best painter of the American scene’.

In 1937, during his second visit to the USA to stay with Conrad Aiken, Burra joined him on a trip to Mexico. They took the train through the American South and on to Mexico City before travelling on to Cuernavaca to stay with Malcolm Lowry – then beginning to write Under the Volcano. Burra suffered from the heat and humidity and after two weeks, with dysentery and rheumatic feet, he returned to Boston alone in a state of collapse and needed to recuperate there for a month before returning to England.

Back in England Burra painted Mexican Church, its composition based on two postcards of churches he’d visited. Burra had been influenced particularly by the Mexican muralists and the prints of Jose Guadalupe Posada with their depictions of lively skeletons. The Day of the Dead theme, central to Under the Volcano is echoed in Skeleton Party, completed nearly 20 years after the trip. The pyramid shapes on the horizon have been identified as slag heaps in an industrial landscape, rather than the twin peaks of Lowry’s Mexican volcanoes.

Although Burra will probably always be best known for his early images of city life, his painting continued to develop throughout his career. Affected by the civil war in Spain, which he had witnessed first-hand, and then the outbreak of world war, he painted scenes of the cruelty of war in the manner of Goya, whom he greatly admired. Key pictures from this period are War in the Sun (1938) painted at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, Soldier’s Backs (1942-3) and the remarkableBeelzebub (1937). In the Second World War he created powerful images of monsters to represent the terror of the war, such as Blue Baby, Blitz over Britain(1941).

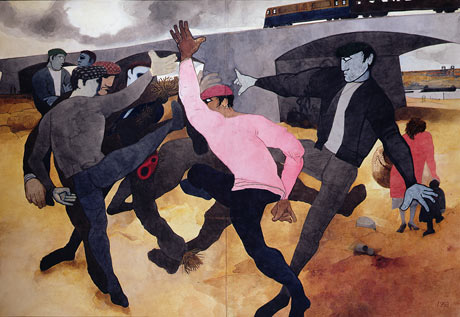

Reviewing the Pallant House exhibition in The Observer, Rachel Cooke suggested that to understand Burra a good place to start is with later painting, The Straw Man (1963), a painting that Pallant House has on long-term loan. It’s a wonderful, dynamic composition, all intersecting diagonals.

The Straw Man is purest essence of Burra: mysterious, antic, wild. Five flat-capped men – or is it six? – appear at first to be dancing, their calves bulging and stockinged, as if they had come from the ballet. Then you understand: these high steps are not celebratory. They are kicking some kind of mannequin. In the right-hand corner of the painting (right-hand corners are important with Burra; the novelist Anthony Powell recalled that this was where the artist began a painting, sweeping diagonally leftwards), a mother pushes a small boy away from the scene, her gesture confirmation, if it were needed, that this is a tale of violence, not joy.

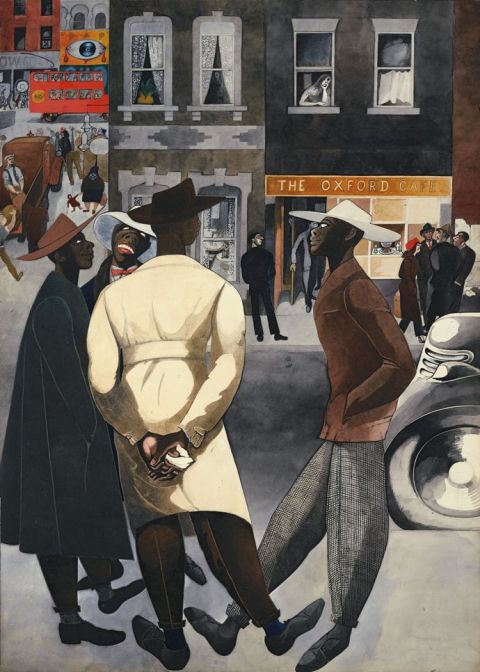

For Simon Martin, Burra is ‘one of the most elusive British artists of the twentieth century’ – long overlooked and underrated.  But recently his reputation has grown dramatically: a record price for one of his works was paid at auction when Zoot Suits sold for £1.8m. That painting, made in 1948, records a London street scene after the arrival of the first Jamaican immigrants to Britain on the SS Windrush.

But recently his reputation has grown dramatically: a record price for one of his works was paid at auction when Zoot Suits sold for £1.8m. That painting, made in 1948, records a London street scene after the arrival of the first Jamaican immigrants to Britain on the SS Windrush.

But recently his reputation has grown dramatically: a record price for one of his works was paid at auction when Zoot Suits sold for £1.8m. That painting, made in 1948, records a London street scene after the arrival of the first Jamaican immigrants to Britain on the SS Windrush.

But recently his reputation has grown dramatically: a record price for one of his works was paid at auction when Zoot Suits sold for £1.8m. That painting, made in 1948, records a London street scene after the arrival of the first Jamaican immigrants to Britain on the SS Windrush.

From the 1950s Burra began to concentrate on painting the English landscape, and from 1959 to his death in 1976 landscape became his main subject matter. At first glance these later landscape paintings can seem quite different from his other work. Whereas much of his earlier work is cluttered and full of detail, there is a great deal of space in the late landscapes. While the earlier paintings are full of eccentric characters and situations, the late landscapes often have few or no people in them.

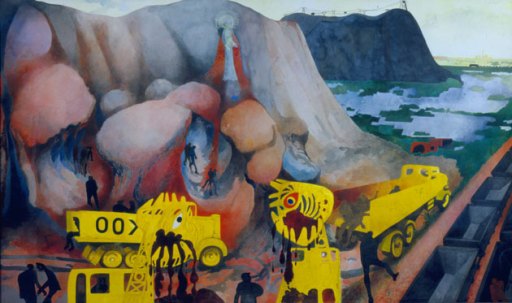

These landscapes are not conventional, picturesque views and there is sometimes a sinister edge to them, with dark brooding colours or unlikely choice of subject matter, such as a menacing petrol tanker or bulldozer. Burra’s late landscapes seem to reflect a return to his roots, but also a concern with the despoilation of the English countryside taking place around him. There are powerful paintings in which diggers, lorries and tractors appear as monsters ripping hungrily through the landscape. Commenting on the late landscapes, Jane Stevenson writes:

In the 1950s, he turned away from the human form to concentrate on landscapes of luminous serenity and weirdly powerful flower pieces. In the 1960s and 70s, he was one of the first artists to protest about the ravaging of the English countryside that went along with the creation of the new motorways, to perceive the real costs of you’ve-never-had-it-so-good. His interest in ecology as well as in the built landscape can be charted in letters and paintings from the end of the war onwards. He produced, for instance, a series of pictures in which the vast diggers and dumpers of the construction industry have morphed into carnivorous dinosaurs, snapping at each other and at the landscape with hostility and greed.

It is his landscapes, though, that for me are the best paintings in this show: transcendent and wonderfully modern – you see Hockney here, and Michael Andrews – even as he nods to the masters. In his last years, Burra toured Britain, chauffeured by his sister, Anne. He went to wild places – to Cornwall, the Peak District, the Yorkshire Moors – and he gawped and gawped. “It fascinated me to watch Edward when the car halted,” said his friend, Billy Chappell. “He might, I thought, have been staring at a blank wall, until I saw the intensity of his gaze.” Only when he got back home did he settle to work, reproducing the heather and the screes, but with curious dashes of his own: a road as blue as a river, a field as brightly coloured as an orange. And often, too, an invader or three: a crawling lorry, a demonic motorbike, a rapacious tractor, even an aeroplane, tiny in the sky, but indelibly black. Black Mountain (1968),English Countryside (1965-7) and An English Scene No 2 (1970) are unforgettable paintings: giant postcards from a man who could not ignore what was happening to England, even if it is sometimes hard to tell if her changing landscape was more a source of regret or delight. Oh, you must see this show. It is fascinating and beautiful – and we will not, perhaps, see its like again: the majority of these works are in private collections. Feast your eyes while you can.

Ultimately Burra’s late landscapes are the most elegiac of his works and arguably his finest. The soft, pleasure-seeking crowds of the 1920s and early 1930s gave way to sombre but more finely crafted pieces informed by the dark middle decades of the twentieth century while the landscapes from the 1960s and 1970s might perhaps best be described as resigned. The eye is still strong but more readily strips away ephemera and the increasing absence of real people from Burra’s paintings reflects his own questioning answer to a question posed by one of his oldest friends, the dancer Billy Chappell. Chappell asked why Burra had been painting transparent people in some of his works: ‘Don’t you find as you get older, you start seeing through everything?’

Of these later landscapes, my outright favourites are Near Whitby, Yorkshire andValley and River, Northumberland (which is in the Tate collection). Both were painted in 1972.

It looks increasingly likely that Edward Burra will be accepted as one of the greatest British artists of the 2oth century. He is a unique figure who should be celebrated for the extraordinary vitality and individuality of his paintings. Burra hated all the talk around pictures and once, in a TV interview, got annoyed at the question, ‘So what does it all mean then?’ Burra, with a twinkle in his eye, responded, ‘Nothing’. He died in 1976 at the age of 72 having lived far longer than anyone could possibly have predicted, and leaving a far greater legacy than he was given credit for at the time.