Kate Rothko Prizel is a strong-looking woman with a disarming smile that she switches on and off like a flashlight. You sit opposite her, trying not to be distracted by the subliminal hum of the canvases on the walls - three early Rothkos to the right of me, and one to the left - and you wonder: how did she do it? How did she survive? Not that she even seems to know herself. 'I always tell people that 19 was the worst year of my life,' she says, with steady understatement. 'And everything has gone uphill from there.'

The smile is duly turned on, and we gaze at one another for a moment. I can't make up my mind whether she is warning me off, or welcoming me in. Kate Rothko turned 19 almost four decades ago, in 1970; in some ways, the events we are about to discuss must feel as though they happened to another person, the facts both gilded and blurred by the weight of years. Then again, they are so starkly awful, it feels almost murderous to bring them up. What defences might I end up knocking down? It's hardly surprising that when she was younger and at medical school, Rothko would find herself categorically denying her relationship to that Rothko, or that later, when she married, she cloaked herself in her married name, Prizel, the better to be invisible.

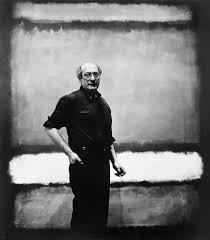

In 1970, on the cold morning of 25 February, the body of her father, the painter,Mark Rothko, was found in his cavernous Manhattan studio. He had overdosed on barbiturates,  and cut an artery in his right arm with a razor blade. He was found in a pool of blood six by eight feet wide, wearing long johns and thick black socks. He left no note. He was 66.

and cut an artery in his right arm with a razor blade. He was found in a pool of blood six by eight feet wide, wearing long johns and thick black socks. He left no note. He was 66.

Six months later, on 26 August, Kate suffered another bereavement, less public, but just as bitter: at the age of 48, her mother, Mell, a book illustrator and Rothko's second wife, had dropped down dead as Kate's brother, Christopher, watched cartoons in the next room.

Or was it? It was the difference between the two funerals of her parents that revealed to Kate, even in the depths of her grief, that this might not, after all, be so. Perhaps the art world was not the bohemian extended family of her imagination.  The two services took place in the same Manhattan funeral parlour, but they could not have been more different. After Mark's funeral, one art world viper is reputed to have remarked that it was 'the best vernissage of the season', and it is certainly true that it was well attended by the great and the good. Among the mourners were Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Philip Guston and Lee Krasner Pollock, not to mention the rows of critics, curators, and collectors. 'At my father's funeral, people were pouring out of the woodwork,' says Kate. 'But I would have to question why they were there, because only about 10 people came to my mother's. She'd known these people for 25 years, and now it was like she was... ' A footnote? 'Yes. It was disillusioning for me to see the superficiality of the art world, and that has never gone away, I must admit. It will never be that idyllic place for me again.'

The two services took place in the same Manhattan funeral parlour, but they could not have been more different. After Mark's funeral, one art world viper is reputed to have remarked that it was 'the best vernissage of the season', and it is certainly true that it was well attended by the great and the good. Among the mourners were Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Philip Guston and Lee Krasner Pollock, not to mention the rows of critics, curators, and collectors. 'At my father's funeral, people were pouring out of the woodwork,' says Kate. 'But I would have to question why they were there, because only about 10 people came to my mother's. She'd known these people for 25 years, and now it was like she was... ' A footnote? 'Yes. It was disillusioning for me to see the superficiality of the art world, and that has never gone away, I must admit. It will never be that idyllic place for me again.'

Within two years, Kate and her brother were fighting a legal battle of Bleak House proportions that few thought they could win - and her parents' 'friends', by now, were even thinner on the ground. 'They were waiting to see which way it was going to go. People were hesitant to talk to me. Only a few were willing to stick their necks out. Lee Krasner , for one, gave multiple interviews in which she said how unwise I was to be fighting the case.'

, for one, gave multiple interviews in which she said how unwise I was to be fighting the case.'

Kate and Christopher sued the executors of their father's estate - his accountant, Bernard Reis, the painter Theodoros Stamos, and a professor of anthropology called Morton Levine (Levine was also, until Kate took steps to remedy the situation, Christopher's guardian) - and his gallery, the Marlborough, claiming that the former had conspired with the latter to 'waste the assets' of Rothko's estate and defraud them of their proper share. The assets were 798 paintings (then estimated to be worth at least $32m). They contended that the three trustees had conspired to sell these Rothkos to the Marlborough at less than their true market value; the gallery had, for instance, got its delighted hands on one group of 100 paintings for just $1.8m, a sum it would pay over 12 years and with no interest, with a down-payment of only $200,000.

The case was to rumble on for more than four years, during which Kate was mostly living in a $90-a-week apartment in Brooklyn, watching what little money she had drain out of her bank account. It was to be seven long years before she had a Rothko of her own; if she wanted to see work by her father, her only option was to visit a gallery. How did she keep going? 'I don't know whether it was that I didn't allow myself to think of the possibility of losing, or whether it simply didn't cross my mind. I only know that I was convinced from a moral standpoint, and that I had a conviction that this was what I had to do, because I knew how upset my father would have been by what was going on.'

To everyone's amazement, Kate and Christopher Rothko won, and the court issued a crushing verdict. The executors were thrown out for 'improvidence and waste verging on gross negligence'. Reis and Stamos, long-time friends of Mark Rothko, were found to have been in conflict of interest; as executors, they could not negotiate with the Marlborough because the company had both of them on its payroll. All contracts between the Marlborough and the Rothko estate were declared void, and the judge awarded damages of more than $9m against Frank Lloyd, the founder of Marlborough Fine Art, who had laundered art through myriad Liechtenstein holding companies, and the executors.

Lee Krasner, swiftly eating her words, removed the estate of her husband, Jackson Pollock, from Marlborough's grasp, and others followed (though Marlborough Fine Art survives, even today). It was, Kate concedes, a magnificent victory - though Reis and Lloyd were, in spite of her best efforts, never punished in a criminal court for their actions. 'No, that's true. One had to make do with the satisfaction of seeing the paintings come back. The judge sat down with me several times [during the litigation] and asked me if I would make a settlement for money. But I always said no, because it wasn't about money.' Nor was it about ownership, or not in the private sense. Kate simply wanted to make sure that her father's wishes became a reality.

Rothko may have been depressed at the end of his life, he may not have been as clear as he should have been when it came to writing a will; but with regard to his work, and where it might end up, he had long held strong views. While selling to private individuals from his studio, he would scrutinise their reactions to paintings; they had to pass a test they did not know they were taking. If they failed, they went home empty-handed, irrespective of the size of their wallets. Lighting, on which wall of a gallery a painting might hang; these things obsessed him.

It was Marlborough's job to sell his work outside America, but so far as his legacy went, it was his wish that it should be seen by the public, and that groups of his paintings should stay together, like siblings. This was why, in the months before he died, he fell upon the idea of a Mark Rothko Foundation; this body, led by Reis, Stamos and Levine, would distribute his work to public galleries. The idea that individual works would disappear into the homes of millionaires was anathema to him.Unfortunately, the court did not rule on paintings that the Marlborough Gallery had already sold. 'We won, but so many didn't come back,' says Kate. 'We were too busy defending the judgment on appeal to go back and appeal for a better judgment. What I've found hardest over the years is looking at what didn't come back. It has been very... distressing. The most painful example I can give you is Homage to Matisse from 1954. It's the one painting I would really like to have; I grew up with it. I gather that it went into a vault somewhere for a number of years and then it came up for auction.'

In 2005, the painting was sold by Christie's New York for $22.4m, a sum that was then a record for a postwar work. 'If something was offered to us in a non-auction situation, I suppose we might make a trade. But at auction, at these prices... no. It's impossible. I finally found out who owns it, and it's another collector, one who will probably never let it out of his private home.'

Do collectors ever invite her to come and see the paintings in their homes? 'Rarely.' Nor are they inclined to make loans. 'I have written for loans on behalf of institutions, to give an extra nudge, but they are invariably refused. Ostensibly, it's because they love the painting so much. But one has to wonder: does price come into it? They are scared of damage, which is always a possibility. I can only say that when the first major retrospective took place in 1978, it was no problem to get loans; now it is increasingly difficult. I find it horrible that art is just another investment.' She laughs. 'No, I don't get invited into too many homes, and perhaps it's just as well because I would probably be very unhappy with the vase on the table in front of the painting.'

Kate Rothko Prizel M D (she is a research pathologist) lives with her husband, an academic, and her youngest daughter in a big (but not vast) Colonial-style house in Washington. I'm sure, given what hangs on her walls, she has a good security system, but if so, it is unobtrusive; I've seen tiny terraces more fortified, and most of those probably contain only the odd David Hockney poster. What you notice immediately are not just the paintings, but the gaps: work, she tells me half-apologetically, is often on loan and, sometimes, when it comes back, the business of rehanging such large and fragile canvases gets put off - and off.

I ask her how many paintings are still in the family. 'It's hard to put a number on things,' she says. 'We had to sell some things to pay legal fees. I can't say what we will have for ever. Christopher and I each have three children. It's clear to me that they care about the paintings, and would rather have them than cash. But there will be estate taxes one day, and here, giving to a museum does not credit towards your estate tax.'

In the 1970s, it was Kate who was 'the point person' when galleries were putting together shows of her father's work, but these days that task falls mostly to Christopher, a psychologist who now works almost exclusively in the interests of the Rothko estate. Even so, Kate will be coming to London for the opening of Tate Modern's Rothko show, the first significant exhibition of his work to be held in Britain for more than 20 years. She is thrilled by the idea of this exhibition in particular because it is not a retrospective, but a unique gathering of Rothko's late work, including the Seagram Murals, originally commissioned to hang in the dining room of the Four Seasons Restaurant in New York, and several other series, including the very last he ever painted, known as Black on Grey.

'Seeing these paintings standing alone may have a very different effect on the audience,' she says. 'This time, there will be no side-by-side comparisons with the bright works of the 1950s, and [thus] the audience will not have a tendency to see the darkening colours as representing a change in his mood. With retrospectives, there is often a feeling [as you approach the monochromatic late works] that this was the ultimate walk towards his suicide. But look at them in isolation, and instead you simply feel something opening up before him. I do not connect any feeling of frustration in him at this time with a frustration over where his work was going. I see these paintings as a new beginning for him rather than a reflection of his mood.

When Rothko committed suicide, many of his friends thought it out of character. As the painter Hedda Sterne put it: 'Who was this man, Rothko, who killed my friend?' Was Kate surprised? 'I guess it was a shock. In one sense, it fit. I knew how depressed he was. But it still seemed so out of character - and then, he did not leave a note, which seemed even more out of character. He was a communicator, on paper and verbally. That seemed extremely strange. He'd been very ill [in 1968, Rothko had suffered an aneurysm, a result of his chronic high blood pressure]. When my mother told me what had happened on the phone, she did not tell me he had killed himself, and I presumed his death was due to one of the illnesses. So I was shocked.''No one would deny that my father was very depressed towards the end of his life. I used to be very engrossed with that idea, too. There was a terrible tendency for me to see the paintings darkening, becoming less accessible emotionally, more hard-edged. I had a hard time separating them from his depression. But then I saw an exhibition at the Menil Collection in Houston, work that followed his completion of the paintings for the Rothko Chapel [commissioned by Dominique and Jean de Menil in the mid-1960s]. I hadn't been familiar with those works. It was a period when I wasn't in the studio a lot, and my father didn't have any at home. It was fascinating to see how those works had grown out of the chapel, and then how they led to the black and greys. That was the beginning of a whole new way of seeing for me.'

What was her father like? 'Oh, this is always a difficult one! He was a very social person, very outgoing.' In biographies, Rothko, who was born in Dvinsk, in what is now Latvia, and who arrived on Ellis Island, New York, in 1913, is always portrayed as a determined socialist. That is why he disapproved of the Four Seasons restaurant, and why he eventually decided to keep the paintings he made for its walls and later to give them to the Tate.

He also liked to make jokes about his peasant background. 'Well, part of that was just his humour. He liked to tell stories about his past. He was anything but a peasant. Education in the family went back three generations. He did remain close to his background. His family was never particularly supportive of his career, and didn't understand it, but there was always a weekly phonecall. He was pretty representative of immigrants of the time, in that he didn't retain his own language - I didn't even learn how to say yes or no in either Yiddish or Russian - but he would always go to the atlas and show me Latvia. He was a great storyteller. He used to tell me that he ice-skated to school. Knowing his athletic abilities, I suspect that was one thing he did not do.'

Kate was interested in his work from early on. Her parents had received membership of the Museum of Modern Art as a baby-shower gift and, on Sundays - after Mell insisted that Rothko leave his studio for the day - the family would go there. Later, Kate remembers visiting Peggy Guggenheim, the great patron and collector, in Venice. 'She took us to Torcello in her motorboat. But the story I always tell is about how, when I was 16, I went cross-country with my father by train. His family lived on the West Coast, and my mother would fly with my brother because he was so young. What is so frustrating, looking back, is that I had three days with my father and, had I been three years older, I would have taken the opportunity to talk to him about his philosophy. But, of course, we both sat there, and for three days, neither one of us really knew what to say to the other. It was an awkward age for me, and I think he felt that awkwardness. I look back and I think: what wasted time!'

Rothko's philosophy was, of course, complicated. He belonged to a generation of artists - his contemporaries included Pollock, Barnett Newman and Clyfford Still - who spent long periods in obscurity and poverty before they were discovered by the critics, at which point their prices rose - and rose. Perhaps this was why, post-1960, he found it so hard to accept his wealth. He paid cash for everything and, according to Robert Motherwell, if he had to go to the bank for any reason, he would slip into 'a depression as intense and prolonged as Kafka writing The Castle'.But it was also that he worried that money would distract from the work itself; he distrusted material success. He was, as Robert Hughes has written, 'one of the last artists in America to believe, with his entire being, that painting could carry the load of major meanings and possess the same comprehensive seriousness as the art of fresco in the 16th century or the novel in 19th-century Russia... his painting accumulated resonance by appealing to myth; but myths were in decline....'

He was determined to think of himself as an outsider even as the riches and the praise - contemporary critics adored Rothko to the point of daffiness - heaped up at his studio door. Did these tensions - the sense you get from his work of a man waiting too long for an epiphany - contribute to his final depression, or was it also, as Lee Seldes suggests in her gripping book about the Rothko trial, that the artist knew that he had signed over too much to the Marlborough? His suicide took place on the same day that a representative from the gallery was due to visit Rothko's warehouse, to choose from the artist's hoard of paintings, something no one had ever done before (he liked to choose paintings for sale himself, and saw this visit, which he felt powerless to resist, as an invasion of privacy).

Kate is in two minds. 'I felt it had never quite sunk in how famous he had become,' she says. 'But then, when Pop art and Op art came so hard on their heels [of the Abstract Expressionists], he felt that he had had only a tiny window of fame, and then what? I think he would have been shocked by what happened after he died because he was absolutely convinced the executors were his friends, and that they'd act in the best interests of the estate. Whether he knew what was going on with the gallery is less clear. He knew he was not... free. I suspect things were planned for a while before he died. It seemed like everything was in place. I can't say if those pressures contributed to his mood, but they would certainly seem to have helped.'

Whatever lay behind her father's final destructive act, Kate hopes that Tate Modern's show will go some way to separating the work from the man, the paint from the biography. She would like people to see the late work as just that - late work - and to relish it for its own sake, the way we might the distinctive late bloom of any other artist, rather than regard it as a symptom of the dark clouds overhead. 'Even I have to step back from the biography at times,' she says. 'From my father as I knew him. Because, sometimes, that leads to misinterpretation.'

For me, the late paintings stand, as much as anything, as a corrective to the earlier work, with its warming yellows and pinks. They remind you that what Rothko most feared and disdained - the idea that his work was regarded as decorative - is too narrow, or at least too easy, a way of seeing him. They are the apotheosis of the existential struggle that lies at the heart of all his work.

And does his daughter still miss the man who gave us the paintings it has been her privilege to fight for, and to protect? I guess, thanks to his work, that her father lives on in a way that most people's parents do not. 'Yes. He does live on in that way. But the paintings are only one part of my father, and not the purely dad part. At family events, I still find myself thinking: I wish he could be here - though not, 38 years on, with the same tearfulness that I felt for... well, the first 20 years.'

· Rothko is at Tate Modern 26 Sep-1 Feb 2009. tate.org.uk/tickets

Rothko's life in brief

1903 Marcus Rothkowitz is born in Latvia. Fearing their sons will be conscripted, the family emigrates to New York in 1913.

1935 Rothko joins with nine other artists to form the 'The Ten', with a mission 'to protest against the reputed equivalence of American painting and literal painting'.

1945 Marries Mary Alice Beistle, his second wife. Five years later Kathy Lynn is born; Christopher follows in 1963.

1959 Has his first one-man show in New York at the Museum of Modern Art.

1969 His Seagram mural paintings for the Four Seasons restaurant in New York are donated to the Tate.

1970 Commits suicide at the age of 66.

He says: 'I am not interested in the relationship between form and colour. The only thing I care about is the expression of man's basic emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, destiny.'

No comments:

Post a Comment