As soon as the trial was over Lindy more or less left the country in haste, was there something strange about that? In 1935, after enduring a three-year ordeal involving the kidnapping and murder of their first born son and the trial of the man accused of committing the crime, Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh chose to flee the country that had made them national icons. Charles, whose battles with the media over issues of privacy were long-standing, confided to a friend that, "We Americans are a primitive people. ...Americans seem to have little respect for the law or the rights of others.".Why would someone do that?

chose to flee the country that had made them national icons. Charles, whose battles with the media over issues of privacy were long-standing, confided to a friend that, "We Americans are a primitive people. ...Americans seem to have little respect for the law or the rights of others.".Why would someone do that?

The Lindberghs found sanctuary in the English countryside. Long Barn, located in the village of Sevenoaks Weald, Kent, is a Grade II listed property and the former home of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson,Nicolson and his wife practiced what today would be called an open marriage. They each had a number of same-sex affairs, and once Harold had to follow Vita to France, where she had "eloped" with Violet Trefusis

Weald, Kent, is a Grade II listed property and the former home of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson,Nicolson and his wife practiced what today would be called an open marriage. They each had a number of same-sex affairs, and once Harold had to follow Vita to France, where she had "eloped" with Violet Trefusis , to try to win her back. However, they remained happy together – in fact, they were famously devoted to each other, writing almost every day when they were separated, for example, because of long diplomatic postings abroad. Eventually, he gave up diplomacy, partly so they could live together in England. They had two sons,Nigel, also a politician and writer, and Benedict, an art historian.

, to try to win her back. However, they remained happy together – in fact, they were famously devoted to each other, writing almost every day when they were separated, for example, because of long diplomatic postings abroad. Eventually, he gave up diplomacy, partly so they could live together in England. They had two sons,Nigel, also a politician and writer, and Benedict, an art historian. . The house is also notable for having famous residents like Douglas Fairbanks

. The house is also notable for having famous residents like Douglas Fairbanks and of course Charles Lindbergh at various times. best known as Vita Sackville-West, she was an English author, poet and gardener. She won the Hawthornden Prize in 1927 and 1933. She was famous for her exuberant aristocratic life, her strong marriage (although she and her husband Harold Nicolson were both gay but had hetro affairs and sex sometimes), her passionate affair with novelist Virginia Woolf,

and of course Charles Lindbergh at various times. best known as Vita Sackville-West, she was an English author, poet and gardener. She won the Hawthornden Prize in 1927 and 1933. She was famous for her exuberant aristocratic life, her strong marriage (although she and her husband Harold Nicolson were both gay but had hetro affairs and sex sometimes), her passionate affair with novelist Virginia Woolf, and Sissinghurst Castle Garden, which she and Nicolson created at Sissinghurst.

and Sissinghurst Castle Garden, which she and Nicolson created at Sissinghurst.

Sissinghurst's garden was created in the 1930s by Vita Sackville-West, poet and gardening writer, and her husband Harold Nicolson, author and diplomat. Sackville-West was a writer on the fringes of the Bloomsbury Group who found her greatest popularity in the weekly columns she contributed as gardening correspondent of The Observer, which incidentally—for she never touted it—made her own garden famous. Sissinghurst's garden is one of the best-loved in the whole of the United Kingdom, drawing visitors from all over the world. The garden itself is designed as a series of "rooms", each with a different character of colour and/or theme, the walls being high clipped hedges and many pink brick walls. The rooms and "doors" are so arranged that, as one enjoys the beauty in a given room, one suddenly discovers a new vista into another part of the garden, making a walk a series of discoveries that keeps leading one into yet another area of the garden. Nicolson spent his efforts coming up with interesting new interconnections, while Sackville-West focused on making the flowers in the interior of each room exciting. Sissinghurst is a small village in the county of Kent in England. Originally called Milkhouse Street (also referred to as Mylkehouse), Sissinghurst changed its name in the 1850s, possibly to avoid association with the smuggling and cockfighting activities of theHawkhurst Gang

Sissinghurst is a small village in the county of Kent in England. Originally called Milkhouse Street (also referred to as Mylkehouse), Sissinghurst changed its name in the 1850s, possibly to avoid association with the smuggling and cockfighting activities of theHawkhurst Gang Two years later, they moved again, this time to a tiny island off the northwest coast of France. One reason for their choice of locales was so Charles could work more closely with Dr. Alexis Carrel, a Nobel-prize-winning French scientist.

Two years later, they moved again, this time to a tiny island off the northwest coast of France. One reason for their choice of locales was so Charles could work more closely with Dr. Alexis Carrel, a Nobel-prize-winning French scientist.

Alexis Carrel above (June 28, 1873 – November 5, 1944) was a French surgeon and biologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1912 for pioneering vascular suturing techniques. He invented the first perfusion pump with Charles A. Lindbergh opening the way to organ transplantation. He is also known for making famous a miraculous healing at Lourdes by witnessing the event. Like many intellectuals before World War II he promoted eugenics. He was a regent for the French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems during the Nazi occupation of Vichy France which implemented the eugenics policies there; his association with the Foundation led to allegations of collaborating with the Nazis

Carrel was regarded as a brilliant medical pioneer for his work in suturing small blood vessels during surgery and in transplanting organs. Lindbergh was eager to discuss with him the potential for successfully operating on a defective human heart. Anne's sister, Elisabeth, had recently suffered a heart attack that permanently damaged her heart's valves. Lindbergh, ever the mechanical wizard, came up with an idea for a heart pump that he revealed to Carrel. Carrel was impressed. The two men collaborated on research and published a book together in 1938, "The Culture of Organs."

In addition to being an innovator in the field of medicine, Carrel held some quite controversial views on the nature of man. A 1935 interview quoted him as saying, "There is no escaping the fact that men were definitely not created equal..." Carrel was in favor of eliminating from society criminals, the insane, and any others who, in his view, weakened civilization's foundation. Lindbergh was taken with Carrel's ideas and thought he had "the most stimulating mind I have ever met." Such notions concerning the superiority of one race over another, and the metering out of society's "weaker" members sounded to some too closely related to the ideas being promoted by Adolf Hitler's Nazi party in Germany.

The Lindberghs had seen the effect of Nazism on a revitalized Germany in 1936. That year, Charles was asked by the American military attaché in Berlin to report on the state of Germany's military aviation program. While in Germany, Charles and Anne attended the Summer Olympic games as the special guests of Field Marshal Hermann Goering, the head of the German military air force, theLuftwaffe. Lindbergh toured German factories, took the controls of state-of-the-art bombers, and noted the multiplying airfields. He visited Germany twice during the next two years. With each visit, he became more impressed with the German military and the German people. He was soon convinced that no other power in Europe could stand up to

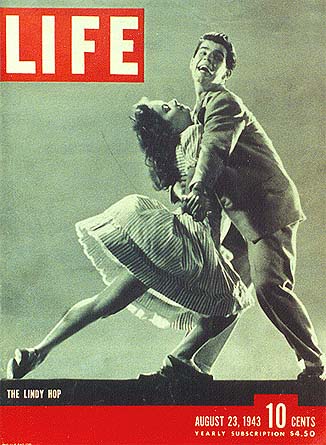

Lindy Hop was associated with Charles Lindbergh's transatlantic airplane flight, completed in 1927. "Lindy" was the aviator's nickname. The reporter interviewing Snowden apparently tied the name to Charles Lindbergh to gain publicity and further his story. While Lindbergh's trans-Atlantic flight may or may not have inspired the name "Lindy Hop", the association between the aviator, George Snowden and the dance continues in Lindy Hop folklore. Germany in the event of war. "

The organized vitality of Germany was what most impressed me: the unceasing activity of the people, and the convinced dictatorial direction to create the new factories, airfields, and research laboratories...," Lindbergh recalled in "Autobiography of Values." His wife drew similar conclusions. "...I have never in my life been so conscious of such a directed force. It is thrilling when seen manifested in the energy, pride, and morale of the people--especially the young people," she wrote in "The Flower and the Nettle." By 1938, the Lindberghs were making plans to move to Berlin.

In October 1938, Lindbergh was presented by Goering, on behalf of the Fuehrer, the Service Cross of the German Eagle for his contributions to aviation. News of Nazi persecution of Jews had been filtering out of Germany for some time, and many people were repulsed by the sight of an American hero wearing a Nazi decoration. Lindbergh, by all appearances, considered the medal to be just another commendation. No different than all the others. Many considered this attitude to be naive, at best. Others saw it as an outright acceptance of Nazi policies. Less than a month after the presenting of the medal, the Nazis orchestrated a brutal assault on Jews that came to be known as Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass. Nazis and their sympathizers smashed the windows of Jewish businesses, burned homes and synagogues, and left scores dead. Between 20,000 and 30,000 Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps. The Lindberghs decided to cancel their plans to move to Germany. below vichy

In October 1938, Lindbergh was presented by Goering, on behalf of the Fuehrer, the Service Cross of the German Eagle for his contributions to aviation. News of Nazi persecution of Jews had been filtering out of Germany for some time, and many people were repulsed by the sight of an American hero wearing a Nazi decoration. Lindbergh, by all appearances, considered the medal to be just another commendation. No different than all the others. Many considered this attitude to be naive, at best. Others saw it as an outright acceptance of Nazi policies. Less than a month after the presenting of the medal, the Nazis orchestrated a brutal assault on Jews that came to be known as Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass. Nazis and their sympathizers smashed the windows of Jewish businesses, burned homes and synagogues, and left scores dead. Between 20,000 and 30,000 Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps. The Lindberghs decided to cancel their plans to move to Germany. below vichy

Having returned to America in April 1939, Lindbergh turned his attention toward keeping his country out of a war in Europe. At the time, most Americans shared his isolationist views. Germany invaded Poland five months later, drawing Britain and France into the war. Two weeks later, Lindbergh delivered his first nationwide radio address in which he urged America to remain neutral. In the speech he criticized President Roosevelt, who believed the Nazis must be stopped in their conquest of Europe. Lindbergh saw Nazi victory as certain and thought America's attention should be placed elsewhere. "These wars in Europe are not wars in which our civilization is defending itself against some Asiatic intruder... This is not a question of banding together to defend the white race against foreign invasion." Building on his belief that "racial strength is vital," Lindbergh published an article in Reader's Digest stating, "That our civilization depends on a Western wall of race and arms which can hold back... the infiltration of inferior blood."

"That our civilization depends on a Western wall of race and arms which can hold back... the infiltration of inferior blood."

As Germany pushed on into France and began its Blitzkreigbombardment of England, Americans began to alter their isolationist views. One group, however, had no such change of heart. The America First Committee was the most powerful isolationist group in the country. Its 850,000 members came from all professions and backgrounds. The AFC was headed by Robert E. Wood, head of Sears Roebuck. Impressed by what they had heard from Charles Lindbergh, the AFC invited him to join their executive committee.

Its 850,000 members came from all professions and backgrounds. The AFC was headed by Robert E. Wood, head of Sears Roebuck. Impressed by what they had heard from Charles Lindbergh, the AFC invited him to join their executive committee.  Lindbergh accepted the invitation, but insisted on drawing no salary. He also insisted on writing his own speeches and would not submit them for approval. One such speech was given in Des Moines, Iowa, on September 11, 1941.

Lindbergh accepted the invitation, but insisted on drawing no salary. He also insisted on writing his own speeches and would not submit them for approval. One such speech was given in Des Moines, Iowa, on September 11, 1941.

With his hero status already greatly tarnished by his philosophical and political beliefs, Lindbergh delivered a speech in Des Moines that fully knocked him off his pedestal.

With his hero status already greatly tarnished by his philosophical and political beliefs, Lindbergh delivered a speech in Des Moines that fully knocked him off his pedestal. Announcing that it was time to "name names," Lindbergh decided to identify what he saw as the pressure groups pushing the U.S. into war against Germany. "The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt Administration." Of the Jews, he went on to say, "Instead of agitating for war,

Announcing that it was time to "name names," Lindbergh decided to identify what he saw as the pressure groups pushing the U.S. into war against Germany. "The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt Administration." Of the Jews, he went on to say, "Instead of agitating for war, Jews in this country should be opposing it in every way, for they will be the first to feel its consequences. Their greatest danger to this country

Jews in this country should be opposing it in every way, for they will be the first to feel its consequences. Their greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government." The speech was met with outrage from numerous quarters. Lindbergh was denounced as an anti-Semite.

lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government." The speech was met with outrage from numerous quarters. Lindbergh was denounced as an anti-Semite.

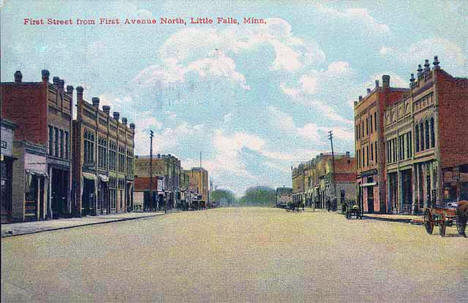

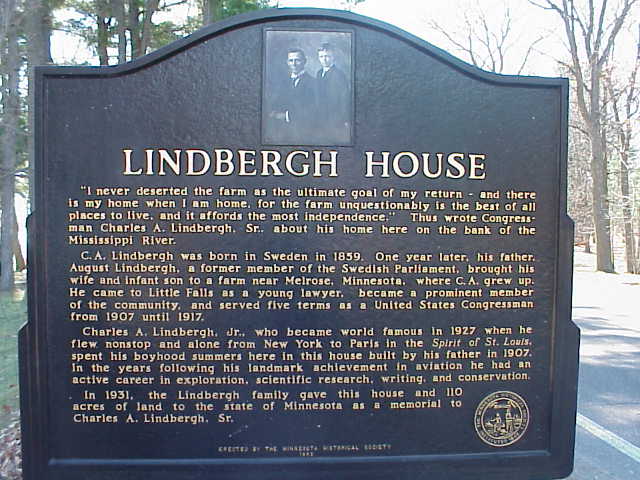

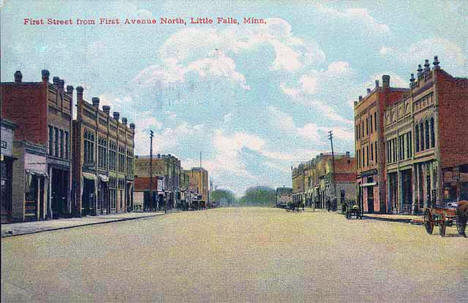

His mother-in-law and sister-in-law publicly opposed his views. Civic and corporate organizations cut all ties and affiliations with him. His name was even removed from the water tower in his hometown of Little Falls, Minnesota.

All debate surrounding U.S. war policy came to an end on December 8, 1941, the day after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. The United States was now at war on two fronts: in Europe and in the Pacific. Despite having resigned his military commission in 1939, Lindbergh was eager to fight for his country.

The United States was now at war on two fronts: in Europe and in the Pacific. Despite having resigned his military commission in 1939, Lindbergh was eager to fight for his country. FDR wouldn't hear of it. "You can't have an officer leading men who thinks we're licked before we start...,"said the President. Rejected by Roosevelt, Lindbergh worked as a private consultant to Henry Ford (a man who'd drawn fire for his own anti-Semitic views. Ford was manufacturing B-24 bombers in a Michigan plant. In 1943, Lindbergh convinced United Aircraft to send him to the Pacific as an observer. His work there involved a good deal more than observation though. Lindbergh flew more than 50 combat missions, including one in which he brought down an enemy fighter.

FDR wouldn't hear of it. "You can't have an officer leading men who thinks we're licked before we start...,"said the President. Rejected by Roosevelt, Lindbergh worked as a private consultant to Henry Ford (a man who'd drawn fire for his own anti-Semitic views. Ford was manufacturing B-24 bombers in a Michigan plant. In 1943, Lindbergh convinced United Aircraft to send him to the Pacific as an observer. His work there involved a good deal more than observation though. Lindbergh flew more than 50 combat missions, including one in which he brought down an enemy fighter. The 42-year-old Lindbergh often bested men half his age in feats demanding intense physical ability. Drawing on his extraordinary piloting skills, Lindbergh instructed others on how to conserve fuel and extend their flying range by up to 500 miles.

The 42-year-old Lindbergh often bested men half his age in feats demanding intense physical ability. Drawing on his extraordinary piloting skills, Lindbergh instructed others on how to conserve fuel and extend their flying range by up to 500 miles.

By August 1945, both Japan and Germany had been soundly defeated. Evidence of Nazi atrocities against Jews shocked the world. Still, Lindbergh refused to admit he was wrong in his assessment of the Nazis. He did indicate, however, that his real hope during the war had been that Hitler and Russian leader, Joseph Stalin, would destroy each other and leave the world safe for the "preservers of Western civilization." He began to speak of the misuse of power as the greatest threat facing mankind.

Still, Lindbergh refused to admit he was wrong in his assessment of the Nazis. He did indicate, however, that his real hope during the war had been that Hitler and Russian leader, Joseph Stalin, would destroy each other and leave the world safe for the "preservers of Western civilization." He began to speak of the misuse of power as the greatest threat facing mankind. In a 1945 speech he said, "History is full of its misuse. There is no better example than Nazi Germany. Power without moral force to guide it invariably ends in the destruction of the people who wield it. Power...must be backed by morality...". With this he may have shown he was a liar and therefore lied on the hauptmann case. Hauptmann was born in Kamenz in the German Empire,

In a 1945 speech he said, "History is full of its misuse. There is no better example than Nazi Germany. Power without moral force to guide it invariably ends in the destruction of the people who wield it. Power...must be backed by morality...". With this he may have shown he was a liar and therefore lied on the hauptmann case. Hauptmann was born in Kamenz in the German Empire, the youngest of five children. He had three brothers and a sister. At age 11, he joined the Boy Scouts (Pfadfinderbund)

the youngest of five children. He had three brothers and a sister. At age 11, he joined the Boy Scouts (Pfadfinderbund) .Hauptmann attended public school (Realschule), but quit at the age of 14. He then worked during the day while attending trade school (Gewerbeschule) at night, studying carpentry for the first year, then switching to machine building (Maschinenschlosser) for the next two years.

.Hauptmann attended public school (Realschule), but quit at the age of 14. He then worked during the day while attending trade school (Gewerbeschule) at night, studying carpentry for the first year, then switching to machine building (Maschinenschlosser) for the next two years.

The kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr. occurred on the evening of March 1, 1932. A man was believed to have climbed up a ladder that was placed under the bedroom window of the child's room and quietly snatched the infant by wrapping him in a blanket.

The kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr. occurred on the evening of March 1, 1932. A man was believed to have climbed up a ladder that was placed under the bedroom window of the child's room and quietly snatched the infant by wrapping him in a blanket. A note demanding a ransom of $50,000 was left on the radiator that formed a windowsill for the room. The ransom was delivered, but the infant was not returned. A corpse identified as the boy's was found on May 12, 1932, in the woods 4 miles (6.4 km) from the Lindbergh home.

A note demanding a ransom of $50,000 was left on the radiator that formed a windowsill for the room. The ransom was delivered, but the infant was not returned. A corpse identified as the boy's was found on May 12, 1932, in the woods 4 miles (6.4 km) from the Lindbergh home. The cause of death was listed as a blow to the head. It has never been determined whether the head injury was accidental or deliberate; some have theorized that the fatal injury occurred accidentally during the abduction. During the opening to the jury in the trial, New Jersey Attorney General David Wilentz

The cause of death was listed as a blow to the head. It has never been determined whether the head injury was accidental or deliberate; some have theorized that the fatal injury occurred accidentally during the abduction. During the opening to the jury in the trial, New Jersey Attorney General David Wilentz  claimed the child died by a fall from the ladder. However during the state's summation, Wilentz would claim the child was killed in the nursery after having been hit in the head with the chisel found at the scene. This material variance in theory as to both the location and cause of death by the state was one of the major points included in Hauptmann's appeal process.

claimed the child died by a fall from the ladder. However during the state's summation, Wilentz would claim the child was killed in the nursery after having been hit in the head with the chisel found at the scene. This material variance in theory as to both the location and cause of death by the state was one of the major points included in Hauptmann's appeal process.

For more than fifty years, Hauptmann's widow fought with the New Jersey courts to have the case re-opened without success. In 1982, the 82-year-old Anna Hauptmann sued the State of New Jersey, various former police officers,

For more than fifty years, Hauptmann's widow fought with the New Jersey courts to have the case re-opened without success. In 1982, the 82-year-old Anna Hauptmann sued the State of New Jersey, various former police officers,  the Hearst newspapers which had published pre-trial articles insisting on Hauptmann's guilt, and former prosecutor David T. Wilentz (then 86 years old), for over $100 million in wrongful-death damages. She claimed that the newly-discovered documents proved misconduct by the prosecution and manufacture of evidence by government agents, all of whom were biased against Hauptmann because he happened to be of German ethnicity. In 1983, the U.S. Supreme Court refused her request that the federal judge considering the case be disqualified because of judicial bias, and in 1984 the judge dismissed her claims.

the Hearst newspapers which had published pre-trial articles insisting on Hauptmann's guilt, and former prosecutor David T. Wilentz (then 86 years old), for over $100 million in wrongful-death damages. She claimed that the newly-discovered documents proved misconduct by the prosecution and manufacture of evidence by government agents, all of whom were biased against Hauptmann because he happened to be of German ethnicity. In 1983, the U.S. Supreme Court refused her request that the federal judge considering the case be disqualified because of judicial bias, and in 1984 the judge dismissed her claims.

"Recently I noticed a statement in a newspaper that the rewards for conviction of the Lindbergh baby kidnap murderer will be given out to claimants before the end of the year. I never put in a formal claim for any of the reward because I did not know that that was necessary, however I shall do so now. I claim to be entitled to a substantial part of the reward for the following major reasons:

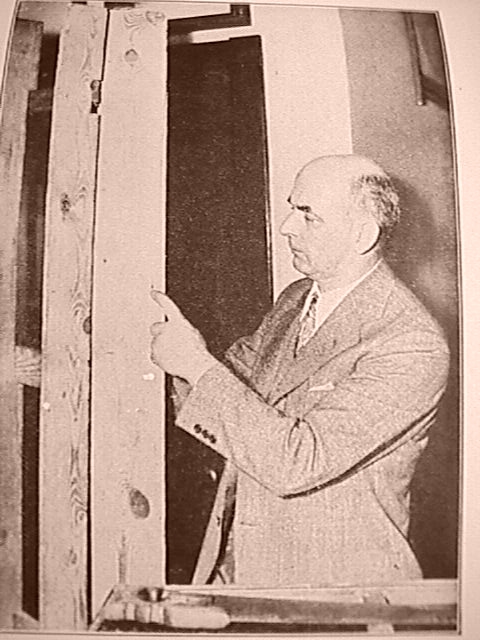

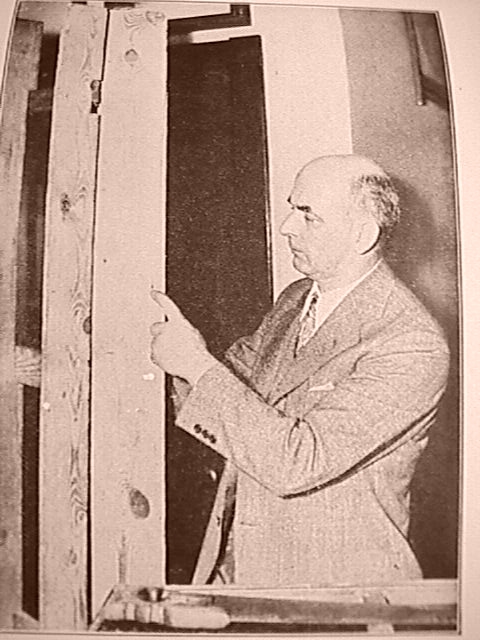

"1. In 1933 I traced two of the upright pieces, or rails, of the ladder to the mill in South Carolina where the lumber from which they were made was manufactured, and from there to the National Lumber and Millwork Company in the Bronx (where Hauptmann had been employed up to the time of the kidnaping and from where he obtained some lumber in December prior to the kidnaping). That was evidence that the kidnaper lived in the Bronx or vicinity since it would not be likely that anyone from a distance would haul such cheap lumber which could be obtained in many places a long way to make the ladder. That information in itself would have been sufficient to lead to Hauptmann's arrest if the police had been more rapid in the investigation of employees of that lumber company upon which they were engaged when the case broke through the passage of some of the ransom money by Hauptmann.

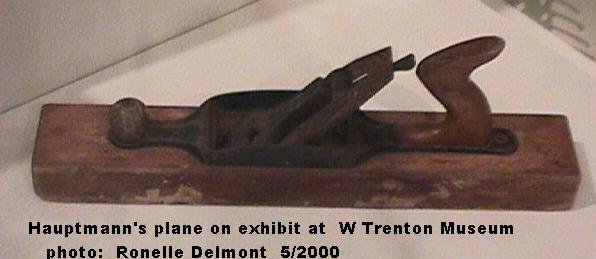

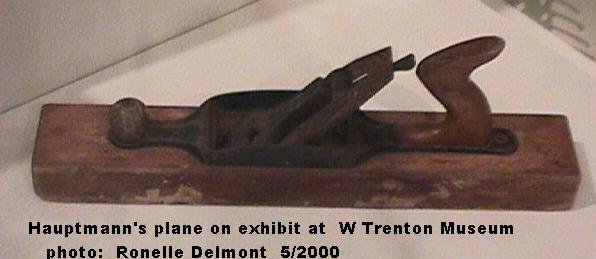

"2. In March, 1933, when I carefully examined the ladder at the request of the New Jersey State Police, I discovered that one of the North Carolina Pine rails and ten of the ponderosa pine rungs were planed on the edges by the same hand plane, which left numerous identifiable ridges due to nicks in the bit of the plane. The fact that two kinds and sizes of pine lumber in the ladder were planed by the same plane indicated that the plane was used when the ladder was made. I told the New Jersey State Police that hand planes in the possession of any suspect should be seized for examination. I found that one of the planes in Hauptmann's possession at the time of his arrest made marks identical with those on the ladder.

I found that one of the planes in Hauptmann's possession at the time of his arrest made marks identical with those on the ladder.

"3. In March, 1933, I also noticed that the rail referred to was planed by hand on BOTH edges and still was as wide as the other 1x4-inch rails. From this I concluded that the piece had been a wider tongue-and-grooved or ship-lapped board and in order to cut it down to a square-edged board of the same size as the other five rails, which were standard 1x4-inch stock, it was necessary to rip and plane BOTH edges. I also noticed that the board had four cut-nail holes in it which indicated previous usage, and that the lumber had not been exposed to the weather for any length of time. I told the New Jersey State Police that if they had any suspect in mind to search his premises or the premises he frequented for some place where a low-grade tongued-and-grooved or ship-lapped board had been nailed down with cut nails "in the interior of a crude building, possibly an attic, shop, warehouse, or barn". After Hauptmann's arrest a New Jersey State Police detective acting on this information noticed that part of a tongued-and-grooved 1x6-inch flooring board was missing from Hauptmann's attic. I determined that the four nail holes in the ladder rail matched four nail holes in the joists in the attic from which the board had been removed. I also determined that the grain of the wood in the ladder rail in question and the board in Hauptmann's attic floor from which part had been removed, as well as the planer marks on the two, matched beyond any reasonable doubt.

"4. I also determined that the 3/4-inch chisel found in Colonel Lindbergh's premises on the night of the kidnaping was of the same make and pattern, with the handle made of the same kind of wood and turned to the same pattern as a 1/4-inch chisel in Hauptmann's possession at the time of his arrest.

"I, therefore, claim that I gave the New Jersey State Police sufficient information to have led to Bruno Richard Hauptmann's arrest, and supplied substantial additional evidence that Hauptmann made the ladder, without which evidence he would not have been convicted. The above facts can be verified by reference to my testimony at Hauptmann's trial.

"Very sincerely yours,

(signed)

"ARTHUR KOEHLER

"Forest Products Laboratory

Madison, Wisconsin"

chose to flee the country that had made them national icons. Charles, whose battles with the media over issues of privacy were long-standing, confided to a friend that, "We Americans are a primitive people. ...Americans seem to have little respect for the law or the rights of others.".Why would someone do that?

chose to flee the country that had made them national icons. Charles, whose battles with the media over issues of privacy were long-standing, confided to a friend that, "We Americans are a primitive people. ...Americans seem to have little respect for the law or the rights of others.".Why would someone do that?

The Lindberghs found sanctuary in the English countryside. Long Barn, located in the village of Sevenoaks

Weald, Kent, is a Grade II listed property and the former home of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson,Nicolson and his wife practiced what today would be called an open marriage. They each had a number of same-sex affairs, and once Harold had to follow Vita to France, where she had "eloped" with Violet Trefusis

Weald, Kent, is a Grade II listed property and the former home of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson,Nicolson and his wife practiced what today would be called an open marriage. They each had a number of same-sex affairs, and once Harold had to follow Vita to France, where she had "eloped" with Violet Trefusis , to try to win her back. However, they remained happy together – in fact, they were famously devoted to each other, writing almost every day when they were separated, for example, because of long diplomatic postings abroad. Eventually, he gave up diplomacy, partly so they could live together in England. They had two sons,Nigel, also a politician and writer, and Benedict, an art historian.

, to try to win her back. However, they remained happy together – in fact, they were famously devoted to each other, writing almost every day when they were separated, for example, because of long diplomatic postings abroad. Eventually, he gave up diplomacy, partly so they could live together in England. They had two sons,Nigel, also a politician and writer, and Benedict, an art historian. . The house is also notable for having famous residents like Douglas Fairbanks

. The house is also notable for having famous residents like Douglas Fairbanks and of course Charles Lindbergh at various times. best known as Vita Sackville-West, she was an English author, poet and gardener. She won the Hawthornden Prize in 1927 and 1933. She was famous for her exuberant aristocratic life, her strong marriage (although she and her husband Harold Nicolson were both gay but had hetro affairs and sex sometimes), her passionate affair with novelist Virginia Woolf,

and of course Charles Lindbergh at various times. best known as Vita Sackville-West, she was an English author, poet and gardener. She won the Hawthornden Prize in 1927 and 1933. She was famous for her exuberant aristocratic life, her strong marriage (although she and her husband Harold Nicolson were both gay but had hetro affairs and sex sometimes), her passionate affair with novelist Virginia Woolf, and Sissinghurst Castle Garden, which she and Nicolson created at Sissinghurst.

and Sissinghurst Castle Garden, which she and Nicolson created at Sissinghurst.

Sissinghurst's garden was created in the 1930s by Vita Sackville-West, poet and gardening writer, and her husband Harold Nicolson, author and diplomat. Sackville-West was a writer on the fringes of the Bloomsbury Group who found her greatest popularity in the weekly columns she contributed as gardening correspondent of The Observer, which incidentally—for she never touted it—made her own garden famous. Sissinghurst's garden is one of the best-loved in the whole of the United Kingdom, drawing visitors from all over the world. The garden itself is designed as a series of "rooms", each with a different character of colour and/or theme, the walls being high clipped hedges and many pink brick walls. The rooms and "doors" are so arranged that, as one enjoys the beauty in a given room, one suddenly discovers a new vista into another part of the garden, making a walk a series of discoveries that keeps leading one into yet another area of the garden. Nicolson spent his efforts coming up with interesting new interconnections, while Sackville-West focused on making the flowers in the interior of each room exciting.

Sissinghurst is a small village in the county of Kent in England. Originally called Milkhouse Street (also referred to as Mylkehouse), Sissinghurst changed its name in the 1850s, possibly to avoid association with the smuggling and cockfighting activities of theHawkhurst Gang

Sissinghurst is a small village in the county of Kent in England. Originally called Milkhouse Street (also referred to as Mylkehouse), Sissinghurst changed its name in the 1850s, possibly to avoid association with the smuggling and cockfighting activities of theHawkhurst Gang Two years later, they moved again, this time to a tiny island off the northwest coast of France. One reason for their choice of locales was so Charles could work more closely with Dr. Alexis Carrel, a Nobel-prize-winning French scientist.

Two years later, they moved again, this time to a tiny island off the northwest coast of France. One reason for their choice of locales was so Charles could work more closely with Dr. Alexis Carrel, a Nobel-prize-winning French scientist.

Alexis Carrel above (June 28, 1873 – November 5, 1944) was a French surgeon and biologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1912 for pioneering vascular suturing techniques. He invented the first perfusion pump with Charles A. Lindbergh opening the way to organ transplantation. He is also known for making famous a miraculous healing at Lourdes by witnessing the event. Like many intellectuals before World War II he promoted eugenics. He was a regent for the French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems during the Nazi occupation of Vichy France which implemented the eugenics policies there; his association with the Foundation led to allegations of collaborating with the Nazis

Carrel was regarded as a brilliant medical pioneer for his work in suturing small blood vessels during surgery and in transplanting organs. Lindbergh was eager to discuss with him the potential for successfully operating on a defective human heart. Anne's sister, Elisabeth, had recently suffered a heart attack that permanently damaged her heart's valves. Lindbergh, ever the mechanical wizard, came up with an idea for a heart pump that he revealed to Carrel. Carrel was impressed. The two men collaborated on research and published a book together in 1938, "The Culture of Organs."

The Lindberghs had seen the effect of Nazism on a revitalized Germany in 1936. That year, Charles was asked by the American military attaché in Berlin to report on the state of Germany's military aviation program. While in Germany, Charles and Anne attended the Summer Olympic games as the special guests of Field Marshal Hermann Goering, the head of the German military air force, theLuftwaffe. Lindbergh toured German factories, took the controls of state-of-the-art bombers, and noted the multiplying airfields. He visited Germany twice during the next two years. With each visit, he became more impressed with the German military and the German people. He was soon convinced that no other power in Europe could stand up to

Lindy Hop was associated with Charles Lindbergh's transatlantic airplane flight, completed in 1927. "Lindy" was the aviator's nickname. The reporter interviewing Snowden apparently tied the name to Charles Lindbergh to gain publicity and further his story. While Lindbergh's trans-Atlantic flight may or may not have inspired the name "Lindy Hop", the association between the aviator, George Snowden and the dance continues in Lindy Hop folklore. Germany in the event of war. "

The organized vitality of Germany was what most impressed me: the unceasing activity of the people, and the convinced dictatorial direction to create the new factories, airfields, and research laboratories...," Lindbergh recalled in "Autobiography of Values." His wife drew similar conclusions. "...I have never in my life been so conscious of such a directed force. It is thrilling when seen manifested in the energy, pride, and morale of the people--especially the young people," she wrote in "The Flower and the Nettle." By 1938, the Lindberghs were making plans to move to Berlin.

In October 1938, Lindbergh was presented by Goering, on behalf of the Fuehrer, the Service Cross of the German Eagle for his contributions to aviation. News of Nazi persecution of Jews had been filtering out of Germany for some time, and many people were repulsed by the sight of an American hero wearing a Nazi decoration. Lindbergh, by all appearances, considered the medal to be just another commendation. No different than all the others. Many considered this attitude to be naive, at best. Others saw it as an outright acceptance of Nazi policies. Less than a month after the presenting of the medal, the Nazis orchestrated a brutal assault on Jews that came to be known as Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass. Nazis and their sympathizers smashed the windows of Jewish businesses, burned homes and synagogues, and left scores dead. Between 20,000 and 30,000 Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps. The Lindberghs decided to cancel their plans to move to Germany. below vichy

In October 1938, Lindbergh was presented by Goering, on behalf of the Fuehrer, the Service Cross of the German Eagle for his contributions to aviation. News of Nazi persecution of Jews had been filtering out of Germany for some time, and many people were repulsed by the sight of an American hero wearing a Nazi decoration. Lindbergh, by all appearances, considered the medal to be just another commendation. No different than all the others. Many considered this attitude to be naive, at best. Others saw it as an outright acceptance of Nazi policies. Less than a month after the presenting of the medal, the Nazis orchestrated a brutal assault on Jews that came to be known as Kristallnacht, the night of broken glass. Nazis and their sympathizers smashed the windows of Jewish businesses, burned homes and synagogues, and left scores dead. Between 20,000 and 30,000 Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps. The Lindberghs decided to cancel their plans to move to Germany. below vichyHaving returned to America in April 1939, Lindbergh turned his attention toward keeping his country out of a war in Europe. At the time, most Americans shared his isolationist views. Germany invaded Poland five months later, drawing Britain and France into the war. Two weeks later, Lindbergh delivered his first nationwide radio address in which he urged America to remain neutral. In the speech he criticized President Roosevelt, who believed the Nazis must be stopped in their conquest of Europe. Lindbergh saw Nazi victory as certain and thought America's attention should be placed elsewhere. "These wars in Europe are not wars in which our civilization is defending itself against some Asiatic intruder... This is not a question of banding together to defend the white race against foreign invasion." Building on his belief that "racial strength is vital," Lindbergh published an article in Reader's Digest stating,

"That our civilization depends on a Western wall of race and arms which can hold back... the infiltration of inferior blood."

"That our civilization depends on a Western wall of race and arms which can hold back... the infiltration of inferior blood."

As Germany pushed on into France and began its Blitzkreigbombardment of England, Americans began to alter their isolationist views. One group, however, had no such change of heart. The America First Committee was the most powerful isolationist group in the country.

Its 850,000 members came from all professions and backgrounds. The AFC was headed by Robert E. Wood, head of Sears Roebuck. Impressed by what they had heard from Charles Lindbergh, the AFC invited him to join their executive committee.

Its 850,000 members came from all professions and backgrounds. The AFC was headed by Robert E. Wood, head of Sears Roebuck. Impressed by what they had heard from Charles Lindbergh, the AFC invited him to join their executive committee.  Lindbergh accepted the invitation, but insisted on drawing no salary. He also insisted on writing his own speeches and would not submit them for approval. One such speech was given in Des Moines, Iowa, on September 11, 1941.

Lindbergh accepted the invitation, but insisted on drawing no salary. He also insisted on writing his own speeches and would not submit them for approval. One such speech was given in Des Moines, Iowa, on September 11, 1941. With his hero status already greatly tarnished by his philosophical and political beliefs, Lindbergh delivered a speech in Des Moines that fully knocked him off his pedestal.

With his hero status already greatly tarnished by his philosophical and political beliefs, Lindbergh delivered a speech in Des Moines that fully knocked him off his pedestal. Announcing that it was time to "name names," Lindbergh decided to identify what he saw as the pressure groups pushing the U.S. into war against Germany. "The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt Administration." Of the Jews, he went on to say, "Instead of agitating for war,

Announcing that it was time to "name names," Lindbergh decided to identify what he saw as the pressure groups pushing the U.S. into war against Germany. "The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt Administration." Of the Jews, he went on to say, "Instead of agitating for war, Jews in this country should be opposing it in every way, for they will be the first to feel its consequences. Their greatest danger to this country

Jews in this country should be opposing it in every way, for they will be the first to feel its consequences. Their greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government." The speech was met with outrage from numerous quarters. Lindbergh was denounced as an anti-Semite.

lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government." The speech was met with outrage from numerous quarters. Lindbergh was denounced as an anti-Semite.

His mother-in-law and sister-in-law publicly opposed his views. Civic and corporate organizations cut all ties and affiliations with him. His name was even removed from the water tower in his hometown of Little Falls, Minnesota.

All debate surrounding U.S. war policy came to an end on December 8, 1941, the day after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

FDR wouldn't hear of it. "You can't have an officer leading men who thinks we're licked before we start...,"said the President. Rejected by Roosevelt, Lindbergh worked as a private consultant to Henry Ford (a man who'd drawn fire for his own anti-Semitic views. Ford was manufacturing B-24 bombers in a Michigan plant. In 1943, Lindbergh convinced United Aircraft to send him to the Pacific as an observer. His work there involved a good deal more than observation though. Lindbergh flew more than 50 combat missions, including one in which he brought down an enemy fighter.

FDR wouldn't hear of it. "You can't have an officer leading men who thinks we're licked before we start...,"said the President. Rejected by Roosevelt, Lindbergh worked as a private consultant to Henry Ford (a man who'd drawn fire for his own anti-Semitic views. Ford was manufacturing B-24 bombers in a Michigan plant. In 1943, Lindbergh convinced United Aircraft to send him to the Pacific as an observer. His work there involved a good deal more than observation though. Lindbergh flew more than 50 combat missions, including one in which he brought down an enemy fighter. The 42-year-old Lindbergh often bested men half his age in feats demanding intense physical ability. Drawing on his extraordinary piloting skills, Lindbergh instructed others on how to conserve fuel and extend their flying range by up to 500 miles.

The 42-year-old Lindbergh often bested men half his age in feats demanding intense physical ability. Drawing on his extraordinary piloting skills, Lindbergh instructed others on how to conserve fuel and extend their flying range by up to 500 miles.

By August 1945, both Japan and Germany had been soundly defeated. Evidence of Nazi atrocities against Jews shocked the world.

Still, Lindbergh refused to admit he was wrong in his assessment of the Nazis. He did indicate, however, that his real hope during the war had been that Hitler and Russian leader, Joseph Stalin, would destroy each other and leave the world safe for the "preservers of Western civilization." He began to speak of the misuse of power as the greatest threat facing mankind.

Still, Lindbergh refused to admit he was wrong in his assessment of the Nazis. He did indicate, however, that his real hope during the war had been that Hitler and Russian leader, Joseph Stalin, would destroy each other and leave the world safe for the "preservers of Western civilization." He began to speak of the misuse of power as the greatest threat facing mankind. In a 1945 speech he said, "History is full of its misuse. There is no better example than Nazi Germany. Power without moral force to guide it invariably ends in the destruction of the people who wield it. Power...must be backed by morality...". With this he may have shown he was a liar and therefore lied on the hauptmann case. Hauptmann was born in Kamenz in the German Empire,

In a 1945 speech he said, "History is full of its misuse. There is no better example than Nazi Germany. Power without moral force to guide it invariably ends in the destruction of the people who wield it. Power...must be backed by morality...". With this he may have shown he was a liar and therefore lied on the hauptmann case. Hauptmann was born in Kamenz in the German Empire, the youngest of five children. He had three brothers and a sister. At age 11, he joined the Boy Scouts (Pfadfinderbund)

the youngest of five children. He had three brothers and a sister. At age 11, he joined the Boy Scouts (Pfadfinderbund) .Hauptmann attended public school (Realschule), but quit at the age of 14. He then worked during the day while attending trade school (Gewerbeschule) at night, studying carpentry for the first year, then switching to machine building (Maschinenschlosser) for the next two years.

.Hauptmann attended public school (Realschule), but quit at the age of 14. He then worked during the day while attending trade school (Gewerbeschule) at night, studying carpentry for the first year, then switching to machine building (Maschinenschlosser) for the next two years.In 1917, Hauptmann's father died. The same year, Hauptmann learned his brother Herman had been killed fighting in France in World War I. Not long after that, he was informed that his brother Max was now dead too, having fallen in Russia. Shortly thereafter, Hauptmann was conscripted and assigned to the artillery.

Upon receiving his orders, he was sent to Bautzen, but was transferred to the 103rd Infantry Replacement Regiment upon his arrival. In 1918, Hauptmann was assigned to the 12th Machine Gun Company at Königsbrück.Hauptmann would claim that he was deployed to Western France with the 177th Regiment of Machine Gunners in either August or September  1918 then fought in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel

1918 then fought in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel .The Battle of Saint-Mihiel was a World War I battle fought between September 12–15, 1918, involving the American Expeditionary Force and 48,000 French troops under the command of U.S. general John J. Pershing

.The Battle of Saint-Mihiel was a World War I battle fought between September 12–15, 1918, involving the American Expeditionary Force and 48,000 French troops under the command of U.S. general John J. Pershing  against Germanpositions. The United States Army Air Service (which later became the United States Air Force) played a significant role in this action

against Germanpositions. The United States Army Air Service (which later became the United States Air Force) played a significant role in this action

Hauptmann would also say he was gassed in either September or October 1918. He also claimed that while his position was being shelled, he was hit in the helmet with a piece of metal. According to him, this knocked him out for "hours" and he was left for dead. When he came to, he crawled back to safety and was back to the "machine guns" that evening.After the war, Hauptmann and a friend robbed two women wheeling baby carriages they were using to transport food on the road between Wiesa and Nebelschutz. The friend wielded Hauptmann's army pistol during the commission of this crime

The friend wielded Hauptmann's army pistol during the commission of this crime

Hauptmann's other charges include burglarizing a mayor's house (using a ladder). Released after three years in prison, he was arrested three months later on suspicion of further burglaries.

1918 then fought in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel

1918 then fought in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel .The Battle of Saint-Mihiel was a World War I battle fought between September 12–15, 1918, involving the American Expeditionary Force and 48,000 French troops under the command of U.S. general John J. Pershing

.The Battle of Saint-Mihiel was a World War I battle fought between September 12–15, 1918, involving the American Expeditionary Force and 48,000 French troops under the command of U.S. general John J. Pershing  against Germanpositions. The United States Army Air Service (which later became the United States Air Force) played a significant role in this action

against Germanpositions. The United States Army Air Service (which later became the United States Air Force) played a significant role in this action

Hauptmann would also say he was gassed in either September or October 1918. He also claimed that while his position was being shelled, he was hit in the helmet with a piece of metal. According to him, this knocked him out for "hours" and he was left for dead. When he came to, he crawled back to safety and was back to the "machine guns" that evening.After the war, Hauptmann and a friend robbed two women wheeling baby carriages they were using to transport food on the road between Wiesa and Nebelschutz.

The friend wielded Hauptmann's army pistol during the commission of this crime

The friend wielded Hauptmann's army pistol during the commission of this crimeHauptmann's other charges include burglarizing a mayor's house (using a ladder). Released after three years in prison, he was arrested three months later on suspicion of further burglaries.

Hauptmann illegally entered the US by stowing away on a liner. Landing in New York in September 1923, the 24-year-old Hauptmann was taken in by a member of the established German community and worked as a carpenter. He married a German waitress in 1925 and became a father eight years later.

Hauptmann was slim and of medium height, but broad shouldered. His eyes were described as being small and deep-set.

The kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr. occurred on the evening of March 1, 1932. A man was believed to have climbed up a ladder that was placed under the bedroom window of the child's room and quietly snatched the infant by wrapping him in a blanket.

The kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr. occurred on the evening of March 1, 1932. A man was believed to have climbed up a ladder that was placed under the bedroom window of the child's room and quietly snatched the infant by wrapping him in a blanket. The cause of death was listed as a blow to the head. It has never been determined whether the head injury was accidental or deliberate; some have theorized that the fatal injury occurred accidentally during the abduction. During the opening to the jury in the trial, New Jersey Attorney General David Wilentz

The cause of death was listed as a blow to the head. It has never been determined whether the head injury was accidental or deliberate; some have theorized that the fatal injury occurred accidentally during the abduction. During the opening to the jury in the trial, New Jersey Attorney General David Wilentz

More than two years after the abduction, authorities finally discovered a promising lead in the form of recent ransom notes which appeared to be the work of the very same individual. Soon this information was leaked to the press, which sought verification that the police were closing in on the kidnapper or kidnappers.

Then, on September 17, 1934, a $10 gold certificate that was part of the ransom was given to a gas station attendant as payment. Gold certificates were rapidly being withdrawn from circulation; to see one was unusual and, in this case, attracted attention. The attendant wrote down the license plate number of the car and gave it to the police. The New York license plate belonged to a dark blue Dodge sedan owned by Hauptmann. After successfully tracing the plate to Hauptmann, he was placed under surveillance by a team consisting of members of the New York Police Department, New Jersey State Police, and the FBI.

On the morning of September 19, 1934, the team followed Hauptmann as he left his apartment on Needham Avenue and East 222nd Street in the Bronx above, but were quickly noticed. As a result, Hauptmann attempted to get away by ignoring red lights and traveling at high speed.below hauptmann home

in the Bronx above, but were quickly noticed. As a result, Hauptmann attempted to get away by ignoring red lights and traveling at high speed.below hauptmann home As the chase continued, Hauptmann was accidentally boxed in by a municipal sprinkler truck between 178th Street and East Tremont Avenue. Hauptmann was placed in handcuffs.

As the chase continued, Hauptmann was accidentally boxed in by a municipal sprinkler truck between 178th Street and East Tremont Avenue. Hauptmann was placed in handcuffs.

in the Bronx above, but were quickly noticed. As a result, Hauptmann attempted to get away by ignoring red lights and traveling at high speed.below hauptmann home

in the Bronx above, but were quickly noticed. As a result, Hauptmann attempted to get away by ignoring red lights and traveling at high speed.below hauptmann home As the chase continued, Hauptmann was accidentally boxed in by a municipal sprinkler truck between 178th Street and East Tremont Avenue. Hauptmann was placed in handcuffs.

As the chase continued, Hauptmann was accidentally boxed in by a municipal sprinkler truck between 178th Street and East Tremont Avenue. Hauptmann was placed in handcuffs.

The trial attracted widespread media attention and was dubbed the "Trial of the Century".Hauptmann was also named "The Most Hated Man In The World". The trial was held in Flemington, New Jersey above, and ran from January 2 to February 13, 1935. Col. Henry S. Breckinridge was Lindbergh's lawyer throughout the case and had acted as an intermediary in the ransom negotiations, assisted by Robert H. Thayer. On discovering his child was missing, Lindbergh had phoned Breckinridge before calling the state police.

was Lindbergh's lawyer throughout the case and had acted as an intermediary in the ransom negotiations, assisted by Robert H. Thayer. On discovering his child was missing, Lindbergh had phoned Breckinridge before calling the state police.

was Lindbergh's lawyer throughout the case and had acted as an intermediary in the ransom negotiations, assisted by Robert H. Thayer. On discovering his child was missing, Lindbergh had phoned Breckinridge before calling the state police.

was Lindbergh's lawyer throughout the case and had acted as an intermediary in the ransom negotiations, assisted by Robert H. Thayer. On discovering his child was missing, Lindbergh had phoned Breckinridge before calling the state police.

Evidence produced against Hauptmann included $14,590 of the ransom money that was found in his garage and testimony alleging handwriting and spelling similarities to that found on the ransom notes. Eight different handwriting experts (Albert S. Osborn, Elbridge W. Stein, John F. Tyrrell, Herbert J. Walter, Harry M. Cassidy, Wilmer T. Souder, Albert D. Osborn, and Clark Sellers] were called by the prosecution to the witness stand, where they pointed out similarities between words and letters in the ransom notes and in Hauptmann's writing specimens (which included documents written before he was arrested, such as automobile registration applications).

One expert (John M. Trendley) was called by the defense to rebut this evidence, while two others (Samuel C. Malone and Arthur P. Meyers) declined to testify; the latter two demanded $500 for their services before even looking at the notes and were promptly dismissed when defense lawyer Fisher declined. Others who claimed expertise (Goodspeed, Braunlich, Foster, Farr, and Thielen) were also retained by the defense. They were told they would testify but, much to their dismay, were never called to the stand by lead attorney Reilly.

One expert (John M. Trendley) was called by the defense to rebut this evidence, while two others (Samuel C. Malone and Arthur P. Meyers) declined to testify; the latter two demanded $500 for their services before even looking at the notes and were promptly dismissed when defense lawyer Fisher declined. Others who claimed expertise (Goodspeed, Braunlich, Foster, Farr, and Thielen) were also retained by the defense. They were told they would testify but, much to their dismay, were never called to the stand by lead attorney Reilly.

Also presented was the handmade ladder used in the kidnapping, along with forensic testimony by Arthur Koehler, chief wood technologist at the Forest Products Laboratory . Koehler had, earlier in the investigation and prior to Hauptmann's arrest, written a report that the ladder's "Rail 16" had probably originated from the interior of a building, possibly an attic, due to the fact there was no rust in the nail holes or discloration around the heads. Koehler asserted this was evidence it had not been exposed to the weather Koehler would testify at the trial that Rail 16 matched a part of a board (S-226) from Hauptmann's attic floor which had a missing piece.

. Koehler had, earlier in the investigation and prior to Hauptmann's arrest, written a report that the ladder's "Rail 16" had probably originated from the interior of a building, possibly an attic, due to the fact there was no rust in the nail holes or discloration around the heads. Koehler asserted this was evidence it had not been exposed to the weather Koehler would testify at the trial that Rail 16 matched a part of a board (S-226) from Hauptmann's attic floor which had a missing piece.

. Koehler had, earlier in the investigation and prior to Hauptmann's arrest, written a report that the ladder's "Rail 16" had probably originated from the interior of a building, possibly an attic, due to the fact there was no rust in the nail holes or discloration around the heads. Koehler asserted this was evidence it had not been exposed to the weather Koehler would testify at the trial that Rail 16 matched a part of a board (S-226) from Hauptmann's attic floor which had a missing piece.

. Koehler had, earlier in the investigation and prior to Hauptmann's arrest, written a report that the ladder's "Rail 16" had probably originated from the interior of a building, possibly an attic, due to the fact there was no rust in the nail holes or discloration around the heads. Koehler asserted this was evidence it had not been exposed to the weather Koehler would testify at the trial that Rail 16 matched a part of a board (S-226) from Hauptmann's attic floor which had a missing piece.Other evidence included Dr. Condon's address and telephone number, which were found written on the inside of one of Hauptmann's closets (Condon had delivered the ransom). Additionally, a hand-drawn sketch which Wilentz suggested was that of a ladder was found in one of Hauptmann's notebooks (S-261). Hauptmann said this picture, along with various other sketches contained therein, had been the work of a child who had drawn in it.

Despite not having an obvious source of employment, he had enough money to purchase a $400 radio and to send his wife on a trip to Germany (the purpose of the trip being to see whether Hauptmann would be arrested for having committed earlier crimes there)]

Hauptmann was positively identified as the man to whom the ransom money was delivered. Other witnesses testified that it was Hauptmann who had spent some of the Lindbergh gold certificates, that he had been seen in the area of the estate in East Amwell, New Jersey near Hopewell

near Hopewell on the day of the kidnapping, and that he had been absent from work on the day of the ransom payment and quit his job two days later.

on the day of the kidnapping, and that he had been absent from work on the day of the ransom payment and quit his job two days later.

near Hopewell

near Hopewell on the day of the kidnapping, and that he had been absent from work on the day of the ransom payment and quit his job two days later.

on the day of the kidnapping, and that he had been absent from work on the day of the ransom payment and quit his job two days later.cemetary of payment

Hauptmann denied being guilty, insisting the box found to contain gold certificates had been left in his garage by a friend named Isidor Fisch, who had returned to Germany in December 1933 and died there in March 1934. Taking the witness stand, Hauptmann claimed that he had found a shoe box left behind by Fisch, which Hauptmann had stored on the top shelf of a kitchen broom closet, later discovering the money which, upon counting, added up to $15,000. He further claimed that since Fisch owed him around $7,500 in business funds, Hauptmann claimed the money for himself. A ledger was found in Hauptmann's home of all his financial transactions, yet no record of the alleged $7,500 debt was listed.

who had returned to Germany in December 1933 and died there in March 1934. Taking the witness stand, Hauptmann claimed that he had found a shoe box left behind by Fisch, which Hauptmann had stored on the top shelf of a kitchen broom closet, later discovering the money which, upon counting, added up to $15,000. He further claimed that since Fisch owed him around $7,500 in business funds, Hauptmann claimed the money for himself. A ledger was found in Hauptmann's home of all his financial transactions, yet no record of the alleged $7,500 debt was listed.

who had returned to Germany in December 1933 and died there in March 1934. Taking the witness stand, Hauptmann claimed that he had found a shoe box left behind by Fisch, which Hauptmann had stored on the top shelf of a kitchen broom closet, later discovering the money which, upon counting, added up to $15,000. He further claimed that since Fisch owed him around $7,500 in business funds, Hauptmann claimed the money for himself. A ledger was found in Hauptmann's home of all his financial transactions, yet no record of the alleged $7,500 debt was listed.

who had returned to Germany in December 1933 and died there in March 1934. Taking the witness stand, Hauptmann claimed that he had found a shoe box left behind by Fisch, which Hauptmann had stored on the top shelf of a kitchen broom closet, later discovering the money which, upon counting, added up to $15,000. He further claimed that since Fisch owed him around $7,500 in business funds, Hauptmann claimed the money for himself. A ledger was found in Hauptmann's home of all his financial transactions, yet no record of the alleged $7,500 debt was listed.

During his trial Hauptmann claimed that, at the time of the kidnapping, he had gone to pick up his wife at Frederiksen’s Bakery on Dyre Avenue in the Bronx where she worked until nine o’clock on Tuesdays. Unfortunately for Hauptmann, when Frederiksen testified, he said that he could not remember if Hauptmann came to the bakery on that particular night. The bakery still exists. It has passed through numerous owners since that time and is now a Caribbean bakery.

Fisch was dying of tuberculosis and Fisch's landlady testified that he could barely afford his $3.50-a-week room. Various witnesses called by Reilly to put Fisch near the Lindbergh house on the night of the kidnapping were discredited in cross-examination with incidents from their pasts, which including criminal records or mental instability.

In his closing summation, Reilly argued that the evidence against Hauptmann was entirely circumstantial, as no reliable witness had placed Hauptmann at the scene of the crime, nor were his fingerprints found on the ladder, the ransom notes, or anywhere in the nursery.

Hauptmann was convicted and immediately sentenced to death by Judge Trenchard who set the date for the week of March 18, 1935.

The Hauptmann Defense appealed to the New Jersey Court of Errors and Appeals which, as a result, delayed the execution. The appeal was then argued on June 29, 1935. Justice Trenchard refused to stay Hauptmann’s scheduled execution when presented with the confession of an inmate who claimed responsibility for the Lindbergh kidnapping.Therefore he condemned hauptmann unjustly and was at the end of the day worse than the kidnappers.

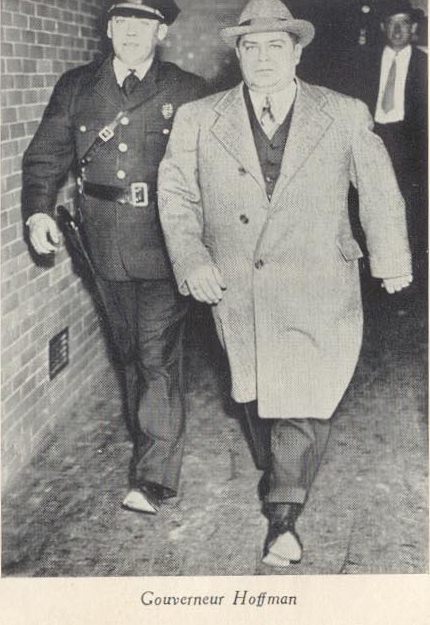

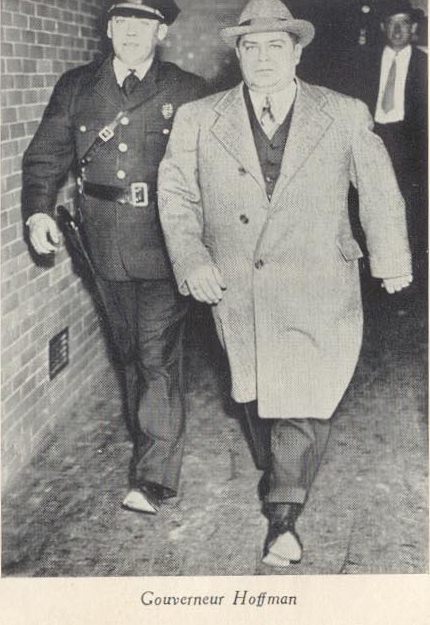

New Jersey Governor Harold G. Hoffman secretly visited Hauptmann in his death row cell on the evening of October 16, 1935, with Anna Bading, a stenographer and fluent speaker of German. Hoffman urged members of the New Jersey Court of Errors and Appeals, then the state's highest court, to visit Hauptmann.hoffman was a falsifier and liar who had embezzled hundreds of thousands from the state.

In late January 1936, while clearly stating he held no position on the guilt or innocence of Hauptmann, Governor Hoffman cited evidence the crime was not a "one person" job. He then directed Col. Schwarzkopf to continue a thorough and impartial investigation into the kidnapping in an effort to bring all parties involved to justice.

As time was quickly running out for Hauptmann, it became known among the press that on March 27, Governor Hoffman was considering a second reprieve of his death sentence, but was actively seeking advice concerning the legality of his right as governor to do so.

On March 30, 1936, Hauptmann's second and final application asking for clemency from the New Jersey Board of Pardons was denied.The Governor would later announce this decision would be the final legal action in this Case, and that he would not grant another reprieve.[2 However, a postponement in the execution would occur once again when the Mercer County Grand Jury, investigating the confession and arrest of Paul Wendel, requested Warden Mark Kimberling for a delay.

This final stay would come to an end when the Mercer County Prosecutor informed Kimberling the Grand Jury had adjourned after voting to discontinue its investigation concerning Wendel without any complaint charging him with murder.

This final stay would come to an end when the Mercer County Prosecutor informed Kimberling the Grand Jury had adjourned after voting to discontinue its investigation concerning Wendel without any complaint charging him with murder.

On April 3, 1936, Hauptmann was executed in "Old Smokey" , the electric chair at the New Jersey State Prison. Hauptmann's last meal consisted of coffee, milk, celery, olives, salmon salad, corn fritters, sliced cheese, fruit salad, and cake. Reporters present at the execution reported that he went to the electric chair without saying a word. He had addressed his last words to his spiritual advisor, Rev. James Matthiesen, minutes prior to being taken from his cell to the death chamber. He reportedly said, "Ich bin absolut unschuldig an den Verbrechen die man mir zur Last legt", which Matthiesen told Gov. Hoffman meant "I am absolutely innocent of the crime with which I am burdened."

, the electric chair at the New Jersey State Prison. Hauptmann's last meal consisted of coffee, milk, celery, olives, salmon salad, corn fritters, sliced cheese, fruit salad, and cake. Reporters present at the execution reported that he went to the electric chair without saying a word. He had addressed his last words to his spiritual advisor, Rev. James Matthiesen, minutes prior to being taken from his cell to the death chamber. He reportedly said, "Ich bin absolut unschuldig an den Verbrechen die man mir zur Last legt", which Matthiesen told Gov. Hoffman meant "I am absolutely innocent of the crime with which I am burdened."

, the electric chair at the New Jersey State Prison. Hauptmann's last meal consisted of coffee, milk, celery, olives, salmon salad, corn fritters, sliced cheese, fruit salad, and cake. Reporters present at the execution reported that he went to the electric chair without saying a word. He had addressed his last words to his spiritual advisor, Rev. James Matthiesen, minutes prior to being taken from his cell to the death chamber. He reportedly said, "Ich bin absolut unschuldig an den Verbrechen die man mir zur Last legt", which Matthiesen told Gov. Hoffman meant "I am absolutely innocent of the crime with which I am burdened."

, the electric chair at the New Jersey State Prison. Hauptmann's last meal consisted of coffee, milk, celery, olives, salmon salad, corn fritters, sliced cheese, fruit salad, and cake. Reporters present at the execution reported that he went to the electric chair without saying a word. He had addressed his last words to his spiritual advisor, Rev. James Matthiesen, minutes prior to being taken from his cell to the death chamber. He reportedly said, "Ich bin absolut unschuldig an den Verbrechen die man mir zur Last legt", which Matthiesen told Gov. Hoffman meant "I am absolutely innocent of the crime with which I am burdened."After the execution, Hauptmann's widow applied for and received the special permission that was required to take her husband's body out of state so that it could be cremated at the U.S. crematory (also called the Fresh Pond Crematory) in the Maspeth neighborhood of Queens, New York.

neighborhood of Queens, New York. The memorial service there was religious (two Lutheran pastors conducted the service in German) and private (under New Jersey law, public services were not permitted for felons, and Anna Hauptmann had agreed to this as a condition of receiving her husband's body) and was attended by only six people (the legal limit under New Jersey rules), but a crowd of over 2,000 gathered outside. Hauptmann's widow had planned to return to Germany with the ashes.In the later part of the 20th century, the case against Hauptmann came under serious scrutiny. For instance, one item of evidence at his trial was a scrawled phone number on a board in his closet, which was the number of the man who delivered the ransom, Dr. John F. Condon. A juror at the trial said this was the one item that convinced him the most, but a reporter supposedly later admitted he had written the number himself.

The memorial service there was religious (two Lutheran pastors conducted the service in German) and private (under New Jersey law, public services were not permitted for felons, and Anna Hauptmann had agreed to this as a condition of receiving her husband's body) and was attended by only six people (the legal limit under New Jersey rules), but a crowd of over 2,000 gathered outside. Hauptmann's widow had planned to return to Germany with the ashes.In the later part of the 20th century, the case against Hauptmann came under serious scrutiny. For instance, one item of evidence at his trial was a scrawled phone number on a board in his closet, which was the number of the man who delivered the ransom, Dr. John F. Condon. A juror at the trial said this was the one item that convinced him the most, but a reporter supposedly later admitted he had written the number himself.

It is also alleged that the eyewitnesses who placed Hauptmann at the Lindbergh estate near the time of the crime were untrustworthy (including one legally blind man who had claimed to have seen Hauptmann near the Lindbergh home), and that neither Lindbergh nor the go-between who delivered the ransom initially identified Hauptmann as the recipient

In fact, Condon, after seeing Hauptmann in a lineup at New York Police Department Greenwich Street Station told FBI Special Agent Turrou that Hauptmann was not "John" - the man to whom Condon claimed he passed the ransom money to in St. Raymond's Cemetery. He further stated that Hauptmann had different eyes, was heavier, had different hair, etc. and that "John" was actually dead because he had been murdered by his confederates.[36] From a distance, while waiting in a car, Lindbergh heard the voice of "John" calling to Condon during the ransom drop-off, but never saw him. Although he testified before the Bronx grand jury that he only heard the words "hey doc" and that it would be very difficult to say he could pick a man by his voice, he did identify Hauptmann's as having the same voice during his trial in Flemington.

The police beat Hauptmann while in custody at the Greenwich Street Station. It has also been alleged that certain witnesses were intimidated, and some claim that the police planted or doctored evidence such as the ladder. There are also allegations that the police doctored Hauptmann's time cards and ignored fellow workers who stated that Hauptmann was working the day of the kidnapping.These and other findings prompted J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI to question the manner in which the investigation and trial were conducted. Hauptmann's widow campaigned until the end of her life to have her husband's conviction reversed.

neighborhood of Queens, New York.

neighborhood of Queens, New York. The memorial service there was religious (two Lutheran pastors conducted the service in German) and private (under New Jersey law, public services were not permitted for felons, and Anna Hauptmann had agreed to this as a condition of receiving her husband's body) and was attended by only six people (the legal limit under New Jersey rules), but a crowd of over 2,000 gathered outside. Hauptmann's widow had planned to return to Germany with the ashes.In the later part of the 20th century, the case against Hauptmann came under serious scrutiny. For instance, one item of evidence at his trial was a scrawled phone number on a board in his closet, which was the number of the man who delivered the ransom, Dr. John F. Condon. A juror at the trial said this was the one item that convinced him the most, but a reporter supposedly later admitted he had written the number himself.

The memorial service there was religious (two Lutheran pastors conducted the service in German) and private (under New Jersey law, public services were not permitted for felons, and Anna Hauptmann had agreed to this as a condition of receiving her husband's body) and was attended by only six people (the legal limit under New Jersey rules), but a crowd of over 2,000 gathered outside. Hauptmann's widow had planned to return to Germany with the ashes.In the later part of the 20th century, the case against Hauptmann came under serious scrutiny. For instance, one item of evidence at his trial was a scrawled phone number on a board in his closet, which was the number of the man who delivered the ransom, Dr. John F. Condon. A juror at the trial said this was the one item that convinced him the most, but a reporter supposedly later admitted he had written the number himself.It is also alleged that the eyewitnesses who placed Hauptmann at the Lindbergh estate near the time of the crime were untrustworthy (including one legally blind man who had claimed to have seen Hauptmann near the Lindbergh home), and that neither Lindbergh nor the go-between who delivered the ransom initially identified Hauptmann as the recipient

In fact, Condon, after seeing Hauptmann in a lineup at New York Police Department Greenwich Street Station told FBI Special Agent Turrou that Hauptmann was not "John" - the man to whom Condon claimed he passed the ransom money to in St. Raymond's Cemetery. He further stated that Hauptmann had different eyes, was heavier, had different hair, etc. and that "John" was actually dead because he had been murdered by his confederates.[36] From a distance, while waiting in a car, Lindbergh heard the voice of "John" calling to Condon during the ransom drop-off, but never saw him. Although he testified before the Bronx grand jury that he only heard the words "hey doc" and that it would be very difficult to say he could pick a man by his voice, he did identify Hauptmann's as having the same voice during his trial in Flemington.

The police beat Hauptmann while in custody at the Greenwich Street Station. It has also been alleged that certain witnesses were intimidated, and some claim that the police planted or doctored evidence such as the ladder. There are also allegations that the police doctored Hauptmann's time cards and ignored fellow workers who stated that Hauptmann was working the day of the kidnapping.These and other findings prompted J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI to question the manner in which the investigation and trial were conducted. Hauptmann's widow campaigned until the end of her life to have her husband's conviction reversed.