I am interested in the capacity of material experimentation as ink, paper, pencil, oil, gouache, linen, wood, wax, stone, lead, copper, bronze, and more, I wanted to seeJasper Johns: Regrets, currently at MoMA even though I had a feeling I might be disappointed, despite my admiration for Johns’ earlier work and for the rigorous and rigorously private studio practice that he maintains at what is considered an advanced age for an artist, 83. Daily studio practice and engagement with craft by older artists was, literally, my matrix, and it’s my hope for my own future.This exhibition premieres Jasper Johns’s most recent body of work, a cohesive group of two paintings, 10 drawings, and two prints created over the last year and a half.

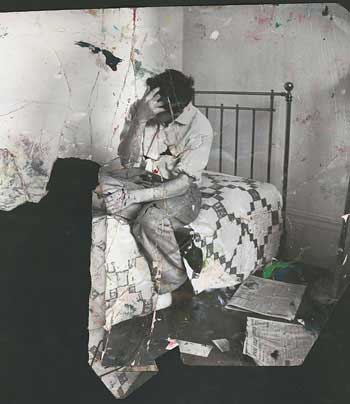

In June 2012, Johns encountered an old photograph of the artist Lucian Freud reproduced in an auction  catalogue. In the picture, Freud sits on a bed, holding his right hand to his forehead in a gesture of weariness or despair. Johns was inspired not only by this scene but also by the damaged appearance of the photograph itself. In the months that followed, he carried the image through a succession of permutations using a variety of mediums and techniques. The title and signature inscribed on most of the works— “Regrets/Jasper Johns”—call to mind a feeling of sadness or disappointment. The words, however, are not without irony: Johns has borrowed them from a rubber stamp he had made several years ago to decline the myriad requests and invitations that come his way.

catalogue. In the picture, Freud sits on a bed, holding his right hand to his forehead in a gesture of weariness or despair. Johns was inspired not only by this scene but also by the damaged appearance of the photograph itself. In the months that followed, he carried the image through a succession of permutations using a variety of mediums and techniques. The title and signature inscribed on most of the works— “Regrets/Jasper Johns”—call to mind a feeling of sadness or disappointment. The words, however, are not without irony: Johns has borrowed them from a rubber stamp he had made several years ago to decline the myriad requests and invitations that come his way.

catalogue. In the picture, Freud sits on a bed, holding his right hand to his forehead in a gesture of weariness or despair. Johns was inspired not only by this scene but also by the damaged appearance of the photograph itself. In the months that followed, he carried the image through a succession of permutations using a variety of mediums and techniques. The title and signature inscribed on most of the works— “Regrets/Jasper Johns”—call to mind a feeling of sadness or disappointment. The words, however, are not without irony: Johns has borrowed them from a rubber stamp he had made several years ago to decline the myriad requests and invitations that come his way.

catalogue. In the picture, Freud sits on a bed, holding his right hand to his forehead in a gesture of weariness or despair. Johns was inspired not only by this scene but also by the damaged appearance of the photograph itself. In the months that followed, he carried the image through a succession of permutations using a variety of mediums and techniques. The title and signature inscribed on most of the works— “Regrets/Jasper Johns”—call to mind a feeling of sadness or disappointment. The words, however, are not without irony: Johns has borrowed them from a rubber stamp he had made several years ago to decline the myriad requests and invitations that come his way.

Seen as a whole, the series reveals the importance of experimentation in Johns’s art, laying bare the cycle of dead ends and fresh starts, the way problems and solutions develop from one work to another, and the incessant interplay of materials, meaning, and representation so characteristic of his work over the last 60 years.

The drawings are mostly small and they take place within the strict boundary of a smaller rectangular area set on a larger piece of paper, effectively setting each drawing into an optical frame, and giving each drawing a formal quality that goes somewhat against the grain of the theme of material and subjective experimentation: Johns never draws outside the lines and there are no accidental smudges or other stereotypical indications of “work” in progress or changes of mind within an individual, except for notes to himself at the bottom of some works, in a careful, small capital letters only print in pencil: “GOYA? BATS? DREAMS?” There is a quality of carefulness and diligence in each work, with each drawing fulfilling a specific set of material specifications and formal analysis of the image. Each is a finished work, enclosed, specific, and private.

The drawings are done with pencil, acrylic, and water-color, in some cases with a Seurat-like dissolution of the figure created by the pebbly effect of rubbing a pencil over a pebbly-surfaced watercolor paper, in other cases a watery smooth print like effect is achieved through ink on a smooth and water repellent vellum like surface.

In most of the works, the pathos embodied in the photograph of Freud–a young man, his face obscured by his hand and by falling strands of hair, seated on a bed–is transferred emotively to the shape of the negative space created by the torn off bottom left hand corner of the print. In the many iterations of the image in which Johns has doubled the picture in a mirror or Rorschach-test format, the human figure is a recessive, barely legible form while the negative shape becomes an important sculptural shape, like a mesa or a tombstone.

The two paintings in the exhibition have a sober, reflective quality with the monumental tombstone form of the negative space in the center framed by intimations of the recalcitrant figure. The group of work as a whole, the whole gift of a limited invitation into his studio functions as a counter-movement to mortality and knowing the age of the artist it is easy to read into the work a reflection on mortality, which is his subject I think.

“One night I dreamed that I painted a large American flag,” Johns has said of this work, “and the next morning I got up and I went out and bought the materials to begin it.” Those materials included three canvases that he mounted on plywood, strips of newspaper, and encaustic paint—a mixture of pigment and molten wax that has formed a surface of lumps and smears. The newspaper scraps visible beneath the stripes and forty-eight stars lend this icon historical specificity. The American flag is something “the mind already knows,” Johns has said,

formed a surface of lumps and smears. The newspaper scraps visible beneath the stripes and forty-eight stars lend this icon historical specificity. The American flag is something “the mind already knows,” Johns has said, but its execution complicates the representation and invites close inspection. A critic of the time encapsulated this painting’s ambivalence, asking, “Is this a flag or a painting?”

but its execution complicates the representation and invites close inspection. A critic of the time encapsulated this painting’s ambivalence, asking, “Is this a flag or a painting?”

formed a surface of lumps and smears. The newspaper scraps visible beneath the stripes and forty-eight stars lend this icon historical specificity. The American flag is something “the mind already knows,” Johns has said,

formed a surface of lumps and smears. The newspaper scraps visible beneath the stripes and forty-eight stars lend this icon historical specificity. The American flag is something “the mind already knows,” Johns has said, but its execution complicates the representation and invites close inspection. A critic of the time encapsulated this painting’s ambivalence, asking, “Is this a flag or a painting?”

but its execution complicates the representation and invites close inspection. A critic of the time encapsulated this painting’s ambivalence, asking, “Is this a flag or a painting?”

No comments:

Post a Comment