HOW could it be that an art movement that took London by storm in the 1920s and 30s – propelling house painters, navvies and painters to international success – could simply disappear? Surely the East London Group should be as celebrated as the Bloomsbury artists, namechecked by critics and young painters?

HOW could it be that an art movement that took London by storm in the 1920s and 30s – propelling house painters, navvies and painters to international success – could simply disappear? Surely the East London Group should be as celebrated as the Bloomsbury artists, namechecked by critics and young painters?

below the ventiliquist by John Cooper

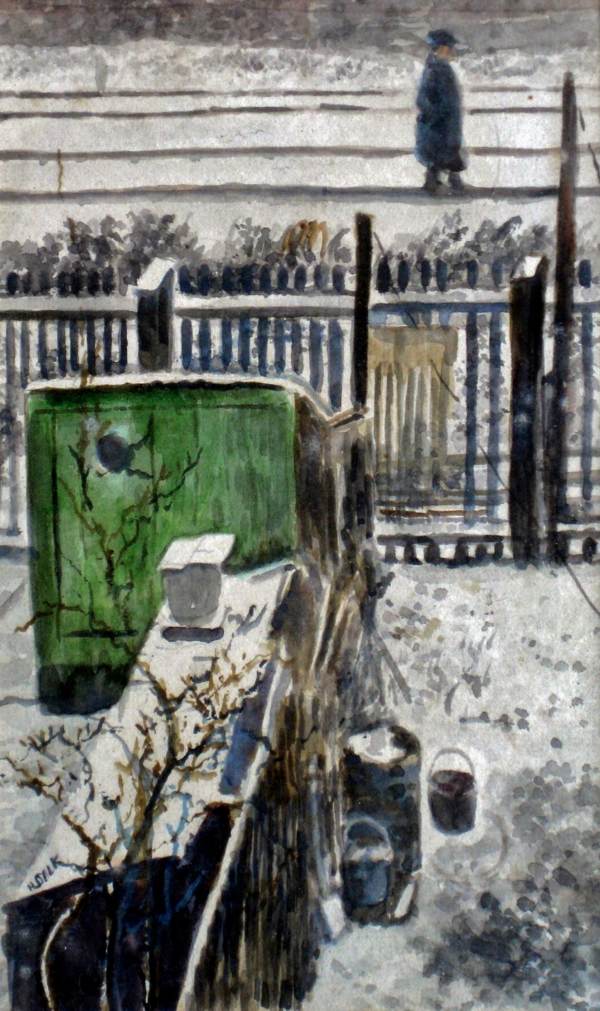

Yet as dramatically as it arose, the grouping was gone. The movement depended on the energy and drive of charismatic leader, John Cooper,and his tragically early death saw the end of his dream.below appledore by cooper

The roots of the movement lay in the slow and steady growth of adult education in London over the previous decades – itself building on the piecemeal establishment of universal education for the working classes over the previous century. Following the Elementary Education Act of 1870 and the Education (London) Act of 1903,

below entrance to the port by Brynhild Parker young East Enders were no longer going into work illiterate and innumerate. Many had their appetite for education awakened, and it was they – working under impossibly difficult conditions, squeezing in adult learning alongside jobs and families – who would form the core the East London Group.

young East Enders were no longer going into work illiterate and innumerate. Many had their appetite for education awakened, and it was they – working under impossibly difficult conditions, squeezing in adult learning alongside jobs and families – who would form the core the East London Group.

young East Enders were no longer going into work illiterate and innumerate. Many had their appetite for education awakened, and it was they – working under impossibly difficult conditions, squeezing in adult learning alongside jobs and families – who would form the core the East London Group.

young East Enders were no longer going into work illiterate and innumerate. Many had their appetite for education awakened, and it was they – working under impossibly difficult conditions, squeezing in adult learning alongside jobs and families – who would form the core the East London Group.

above john cooper

In 1924, the Bethnal Green Men’s Institute Art Club held its first exhibition at the Bethnal Green Museum. The space had been opened as a branch of the South Kensington (now the Victoria and Albert) Museum in 1872 –

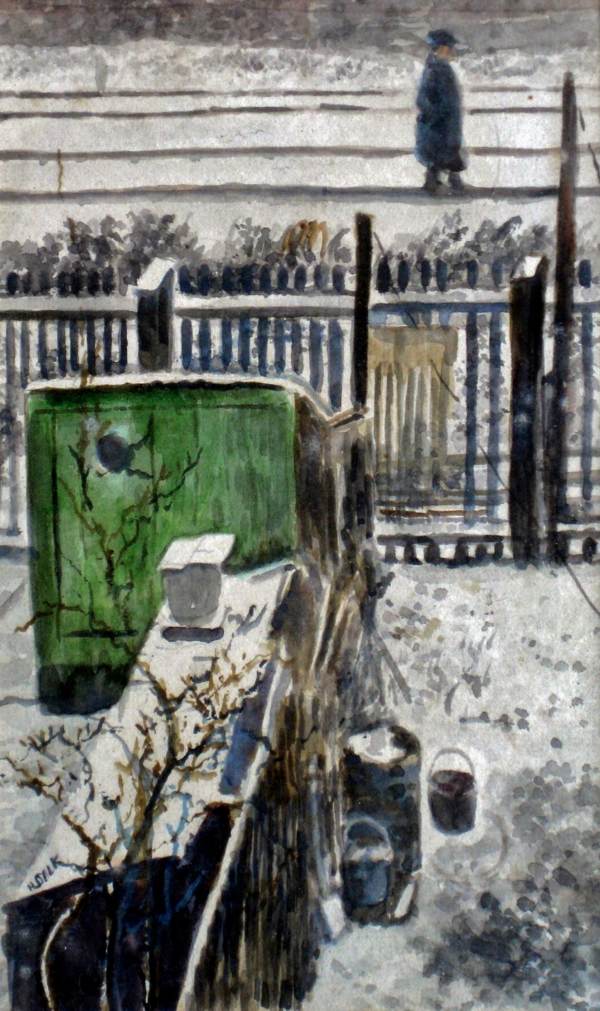

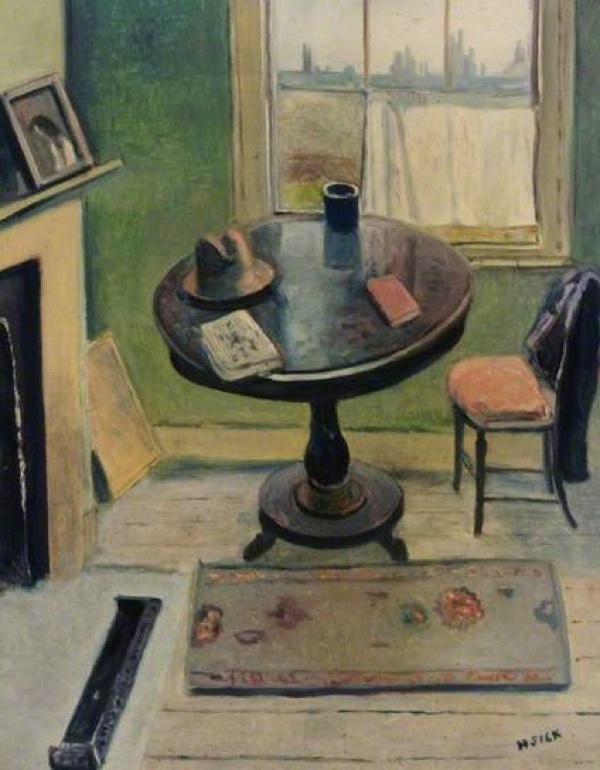

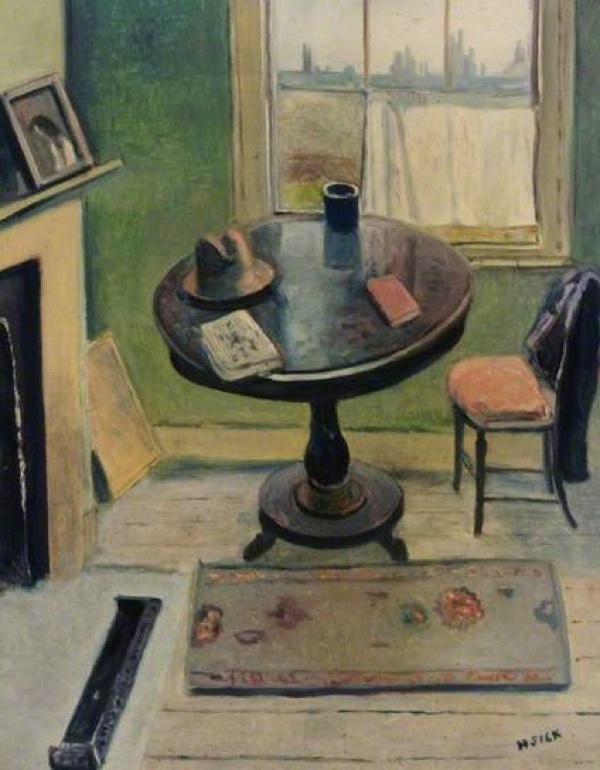

below henry silk it’s now the Museum of Childhood. It proved a marvellous catalyst: both inspiring local artists and providing a venue for exposition of their work.

it’s now the Museum of Childhood. It proved a marvellous catalyst: both inspiring local artists and providing a venue for exposition of their work.

it’s now the Museum of Childhood. It proved a marvellous catalyst: both inspiring local artists and providing a venue for exposition of their work.

it’s now the Museum of Childhood. It proved a marvellous catalyst: both inspiring local artists and providing a venue for exposition of their work.

below Henry Silk The Institute librarian, AK Sabin, wrote in his introduction to the catalogue (the first of several he would pen) that the Bethnal Green group had been started “little more than a year ago by a warehouseman, a house decorator,

The Institute librarian, AK Sabin, wrote in his introduction to the catalogue (the first of several he would pen) that the Bethnal Green group had been started “little more than a year ago by a warehouseman, a house decorator,

The Institute librarian, AK Sabin, wrote in his introduction to the catalogue (the first of several he would pen) that the Bethnal Green group had been started “little more than a year ago by a warehouseman, a house decorator,

The Institute librarian, AK Sabin, wrote in his introduction to the catalogue (the first of several he would pen) that the Bethnal Green group had been started “little more than a year ago by a warehouseman, a house decorator,

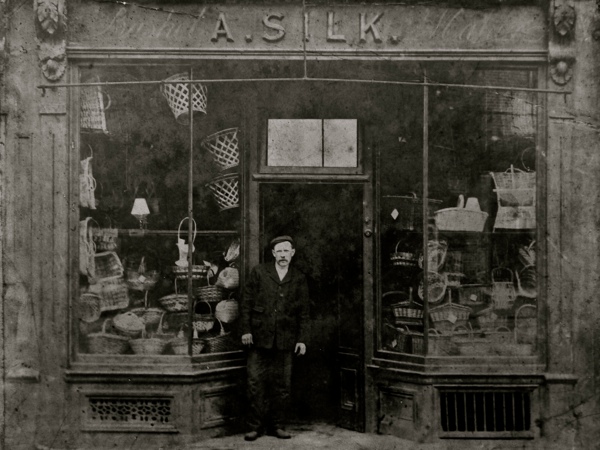

Henry Silk above at shop of his uncle

Helen McCloy filing an insightful survey of the group’s achievements for the Boston Evening Transcript, judged Silk to have “the keenest technical sense of all the limitations and possibilities of paint.” Coincident with McCloy’s article, Hope Christie Skillman in the College Art Association’s publication Parnassus, distinguished Silk as “perhaps the most original and personal of the Group,” finding in his works such as The Railway Track, The Platelayers, The Tyre Dump and The Wireless Set, “beauty where we were taught not to see it.”

Silk’s early life is obscure. He was an East Ender, born on Christmas Day 1883, who worked as a basket maker for an uncle, Abraham Silk, at his workshop and shop in the Bow Rd. Fruit baskets were in great demand then and men making baskets became features of Silk’s pictures. “He used to work for three weeks at basket-making and spend the fourth in the pub,” Group member Walter Steggles remembered, describing Silk’s erratic work and drink habits. Yet Steggles also spoke of Silk with affection, admitting“He was a kind-hearted man who always looked older than his years.”

Silk was the uncle of Elwin Hawthorne, one of the leading members of the group, and lived for a time with that family at 11 Rounton Rd in Bow. Elwin’s widow Lilian – who, as Lilian Leahy, also showed with the group – remembered Silk as “generous to others but mean to himself. He would use an old canvas if someone gave it to him rather than buy a new one.” This make-do-and-mend ethos was common among the often-hard-up Group members when it came to framing too. Cooper directed them to E. R. Skillen & Co, in Lamb’s Conduit St, where Walter Steggles used to buy old frames that could be cut to size.

During the First World War, the young Silk was already sketching. Even on military service in his early thirties, during which he was gassed, he would draw on whatever he could find to hand. By the mid-twenties, he was attending classes at the Bethnal Green Men’s Institute and exhibited when the Art Club had its debut show at Bethnal Green Museum early in 1924. The Daily Chronicle ran a substantial account of the spring 1927 exhibition, highlighting Henry Silk, the basket maker, whose paintings depicted “Zeppelins and were bought by an officer ‘for a bob

.’”John Cooper's mosaic for the Wharrie Cabmens Shelter

Yorkshireman, John Cooper, who had trained at The Slade, taught at Bethnal Green and, when he moved to evening classes at the Bow & Bromley Evening Institute, he took many students with him including George Board, Archibald Hattemore, Elwin Hawthorne, Henry Silk, the Steggles brothers and Albert Turpin

.The Wharfe at Arthington Viaduct by John Cooper, mid- thirties They were members of the East London Art Club that had its exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the winter of 1928, part of which transferred to what is now the Tate Britain early in 1929. These activities prompted the series of Lefevre Galleries annual East London Group shows throughout the thirties, with their sales to many notable private collectors and public galleries, and huge media coverage. below old ford

They were members of the East London Art Club that had its exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the winter of 1928, part of which transferred to what is now the Tate Britain early in 1929. These activities prompted the series of Lefevre Galleries annual East London Group shows throughout the thirties, with their sales to many notable private collectors and public galleries, and huge media coverage. below old ford

They were members of the East London Art Club that had its exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the winter of 1928, part of which transferred to what is now the Tate Britain early in 1929. These activities prompted the series of Lefevre Galleries annual East London Group shows throughout the thirties, with their sales to many notable private collectors and public galleries, and huge media coverage. below old ford

They were members of the East London Art Club that had its exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in the winter of 1928, part of which transferred to what is now the Tate Britain early in 1929. These activities prompted the series of Lefevre Galleries annual East London Group shows throughout the thirties, with their sales to many notable private collectors and public galleries, and huge media coverage. below old ford

Henry Silk was a prolific artist. He contributed a significant number of works to the Whitechapel show in 1928, remained a significant exhibitor at the East London Group-associated appearances, showed with the Toynbee Art Club and at Thos Agnew & Sons. Among his prestigious buyers were the eminent dealer Sir Joseph Duveen, Tate director Charles Aitken and the poet and artist Laurence Binyon. Another was the writer J. B. Priestley, Cooper’s friend, who over the years garnered an impressive and well-chosen modern picture collection. Silk was also regarded highly by his East London Group peers, Murroe FitzGerald, Hawthorne’s wife Lilian and Walter Steggles, who all acquired works of his.

As each of the East London Group artists acquired individual followings as a result of the annual and mixed exhibitions, the Lefevre Galleries astutely organised solo shows for several of them. Elwin Hawthorne, Brynhild Parker and the brothers Harold & Walter Steggles all benefited.

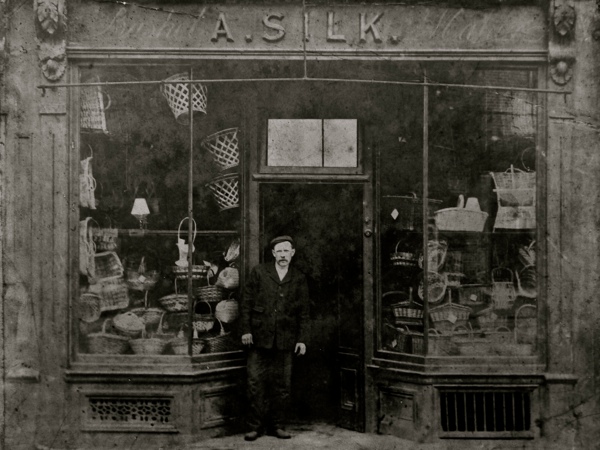

Elwin Hawthorne, Brynhild Parker and the brothers Harold & Walter Steggles all benefited.  Yet, in advance of these, in 1931 Silk had a solo show of watercolours at the recently established gallery Walter Bull & Sanders Ltd, in Cork St. The small exhibition was characterised by an array of still lifes and interiors. Writing in The Studio magazine two years earlier, having visited Cooper’s Bow classe, F. G. Stone noted that Silk often saw “a perfect design from an unusual angle, and he has a Van Goghian love of chairs and all simple things.”

Yet, in advance of these, in 1931 Silk had a solo show of watercolours at the recently established gallery Walter Bull & Sanders Ltd, in Cork St. The small exhibition was characterised by an array of still lifes and interiors. Writing in The Studio magazine two years earlier, having visited Cooper’s Bow classe, F. G. Stone noted that Silk often saw “a perfect design from an unusual angle, and he has a Van Goghian love of chairs and all simple things.”

Elwin Hawthorne, Brynhild Parker and the brothers Harold & Walter Steggles all benefited.

Elwin Hawthorne, Brynhild Parker and the brothers Harold & Walter Steggles all benefited.  Yet, in advance of these, in 1931 Silk had a solo show of watercolours at the recently established gallery Walter Bull & Sanders Ltd, in Cork St. The small exhibition was characterised by an array of still lifes and interiors. Writing in The Studio magazine two years earlier, having visited Cooper’s Bow classe, F. G. Stone noted that Silk often saw “a perfect design from an unusual angle, and he has a Van Goghian love of chairs and all simple things.”

Yet, in advance of these, in 1931 Silk had a solo show of watercolours at the recently established gallery Walter Bull & Sanders Ltd, in Cork St. The small exhibition was characterised by an array of still lifes and interiors. Writing in The Studio magazine two years earlier, having visited Cooper’s Bow classe, F. G. Stone noted that Silk often saw “a perfect design from an unusual angle, and he has a Van Goghian love of chairs and all simple things.”

three deck hands waiting for a ship, and a haddock smoker”. The wonder was that these East Enders, amid family commitments, working long hours

and jostling for piecework, were able to fit in instruction two nights study a week after a hard day at work, paying for their own materials from their sparse wages. Soon, the group numbered 30 or more active members, and that first show featured 88 works by 15 members. Only one of their number would go on to join the later East London Group: George Board, who showed seven watercolours. But more important was the interest the show sparked. Among the crowds at the 1925 Bethnal Green show were the young Harold and Walter Steggles. The brothers would go on to be key members of the later East London Group.

The Steggles boys showed an eye for commerce that was foreign to the more high-minded Sabin. He refused to put prices in his catalogue, believing that “the reflection this pursuit of artistic expression makes upon the artist himself – the new background it brings

into his life – is the most urgent and important thing”. Harold Steggles however thought pricing more likely to put money in the pocket of the artist, and all the later East London Group catalogues would feature prices. Significantly, those shows they would garner commercial as well as critical success, being shown in West End galleries and around the world.

But by now there was an even more significant shift. Percy Wagstaff, in charge of the classes at Wolverley Street School, in Bethnal Green Road, had recruited the charismatic and inexhaustible (for now at least) John Cooper. Cooper had walked into Civvy Street after service in the Great War, and invested his demob pay in three years’ study at the Slade School of Fine Art, leaving in 1922. “Having no money, I had to get teaching, and taught in East London in the evenings,” he explained to collector Sir Michael Sadler years later. Cooper immediately shook up the teaching and the group had an instant triumph.

And others swiftly followed. The 1927 exhibition was covered extensively by the Daily Chronicle, with headlines including “Workmen as artists” and “Window cleaner’s work in East End show”. The window cleaner was Albert Turpin, a prolific painter who would later go on to be mayor of Bethnal Green. There was basketmaker Henry Silk and his paintings of Zeppelins. Spanish Onions was a still life by Bow engine driver EH Hawthorn, while Victoria Park park-keeper, C Warren took time off from “chivvying small boys about” to commit details of park life to canvas. There was RH James, stone deaf and who hadn’t picked up a brush until he was 58. His father, grandfather and three uncles had all been drowned at sea, and that had, unsurprisingly, put RH off a life on the ocean wave. Ironically, many of his paintings were seascapes. And BR Swinnerton had executed a “very homely little picture”, The Place I Love showing his wife and child at the hearth. He declared that he would never attempt such as scene again as “the rogues won’t keep still!”bought by the National Gallery of British Arts (now Tate Britain). Hattemore’s story was tailormade for the popular press. He was the “navvy artist”, too broke to buy a canvas and so rendering his picture on calico. Apart from his few months’ study at the Institute, Archibald was entirely self-taught. With a wife and three children, and a weekly wage of only £2 and 14 shillings for his job at the Metropolitan Water Board, just getting the time and materials together to paint was a struggle. When Cooper saw the work he was stunned; other critics declared it to have “a Velasquez touch”. But for Hattemore aesthetics had to go hand in hand with commerce. When Cooper told him he wanted to show his picture more widely, Hattemore’s response was sanguine. “They tell me it is a great honour. I hope it will mean a way out for me. It will… if somebody buys the picture!” The Duveen Fund promptly did and Hattemore was on his way.

William Finch taught at the Institute at the time (he went on to become a famed art teacher and only died in 2003) and painted a vivid penThe Institute had been begun in 1920 with an instruction to Sabin to “make good” within three years or it would be shut down.The classes far exceeded merely making good. Sir Percy Harris was tasked with delivering a report on progress ten years on, and described it with a new home (albeit a rather grim building) at 229 Bethnal Green Road. Bedecking the facade was a banner, made by member J Cordwell, proclaiming that it was “The house of 2000 men”. Cooper’s energy and ideas had fired an extraordinary growth in membership. “My idea is to stimulate and direct these talented men…they have an abundance of strong individuality and fine fresh pictorial ideas…I don’t fritter away this energy…in drawing common objects.” So there were the odd still lives (those onions for instance) but Cooper was increasingly forcing his students out of the classroom, to paint the East End in all its grit, grime and reality.

Over a few short years, Cooper wrought an astonishing change. From a lively evening class in Bethnal Green, by 1936 East London Group members were being exhibited at the Venice Biennale, among the most prestigious showcases on the international art scene. Alongside such luminaries as Barbara Hepworth, Sir Alfred Gilbert and Duncan Grant were Elwin Hawthorne with Una Via Di Londra and WJ Steggles, with Scena Prosso Chichester. John Cooper didn’t exhibit his own work, but he had the satisfaction of knowing that “two raw amateurs heportrait of those days. “My Bethnal Green gang produced good and varied paintings. It was a varied bunch and tough – a formerly well-known professional boxer, a cooper, a London street busker, a market trader, an injured window cleaner.” John Cooper went further. Arriving at Bow he soon concluded that he had the raw material to begin a whole new school of art. All he had to do was get the members “to stop painting film stars…and to paint what was all about them, say a dingy bedroom”. He dragged his students away from “copying bad pictures” and winnowed out the less talented or committed men. And in 1929, Cooper made a decisive shift, renaming the artists ‘The East London Group’ and signing a contract with West End gallery Alex, Reid & Lefevre to host the annual show. It meant greater exposure for his crew, and increased sales.

But even as the Group found further success there were signs of decline and dissolution. The eighth annual Lefevre show in 1936 would prove to be the last, amid fears that the grouping might be becoming stale. And amid the usual praise in the press that year were murmurings of dissent, with the Morning Post critic believing that “its members were hysterically overpraised in the beginning”. There is always a critical backlash of course, and the work of WJ Steggles, Brynhild Parker and Phyllis Bray was still garnering commercial and critical success, but there were other cracks appearing too.had welcomed into his Bow evening classes a dozen years before were reckoned good enough to show alongside the best in British art.” Cooper’s work ethic was legendary, teaching all around London and increasingly moving into mosaic work. He encouraged his students to exhibit more widely, and in December 1935 came another milestone for the group. Cooper’s assistant and then wife, Phyllis Bray, was asked to create three large murals for the New People’s Palace in Mile End.

The marriage of Cooper and Bray was swiftly unravelling (in part prompted by an attachment Phyllis formed to an architect during her People’s Palace work),and by September 1936, the two fiery personalities were living apart in Bow. It of course made teaching together difficult. And with the outbreak of war, Cooper’s situation declined. Teaching hours had been cut, and he was now struggling financially. Things improved with a job at the Air Ministry drawing aircraft, but the already emotionally volatile artist was rocked further when his flat

was bombed in an air raid. Cooper had to leave his Ministry job, citing “a long breakdown”. At least part of the reason, according to his doctors, was overwork, and he returned to his native Yorkshire to recuperate. His health declined, and John Cooper died in his sleep at Leeds Infirmary in February 1943. He was just 48 years old. The death of Cooper undermined the possibility of any revival in the East London Group after the war. The group possessed huge talents, but relied heavily on

Guardian Angels Church, Mile End, by Elwin Hawthorne

Cooper urged his students to paint the world around them and Silk met the challenge by depicting landscapes near his home in the East End, also sketching while on holiday in Southend and as far away as Edinburgh. Writing the foreword to the catalogue of the second group exhibition at Lefevre in December 1930, the critic R. H. Wilenski said that French artists were fascinated by the “cool, frail London light.” and many asked him “what English artists have made these aspects of London the essential subject of their work.” He responded, “The next time a French artist talks to me in this manner I shall tell him of the East London Group, and the members’ names that I shall mention first in this connection will be Elwin Hawthorne, W. J. Steggles and Henry Silk.”

the energy and drive of Cooper to make things happen – without him the engine was gone.

From Bow to Biennale: Artists of the East London Group by David Buckman. Published by Francis Boutle, £25

No comments:

Post a Comment