LAUGHING TORSO

. We made friends and she asked

him to bring me to her house. I had never been

to the Opera House before and was much impressed

at the chic of the French women.

at the chic of the French women.

They were very

much made up, but the only grand and aristocratic

woman

that I could see was sitting in a box opposite

to us with some friends,

and I asked who she could

and I asked who she could

be. My friend, Winzer, who knew nearly everyone

there, told me that it was

Lady Juliet Duff. I met

her some years afterwards at the Princess Murat's.

During the intervals we went to the promenade and

talked to Diaghilev and the Princess.

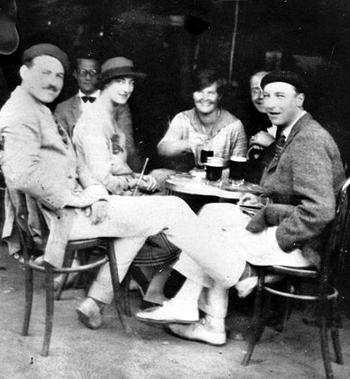

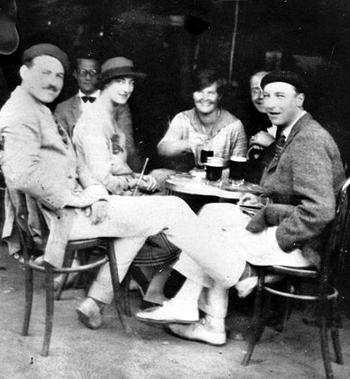

In London I had met Andre Gide. One day he

came up to the Cafe Parnasse, which has now be

came up to the Cafe Parnasse, which has now be

come part of the Rotonde.

This was at that time

miich the most amusing cafe in Montparnasse. He

was delighted to see me and had with him a young

man called Marc Allegri, who, a year or two ago,

went to the Congo with Gide and made a wonderful

film of the natives there

.

Several English officers

who had been at the Peace Conference were still in

Paris and used to come to the Parnasse in the even

ings.

They knew many songs and we found an

American who sang too, and we would spend the

evenings singing. Andre Gide would come up and

listen.

He spoke English almost perfectly and I

think enjoyed our singing, although it got very loud

and noisy as the evening wore on. I had left the

Hotel Victor and was living in a hotel opposite the

Gare Montparnasse. Marc Allegri said that he

would like to see some of my work, some of which

I had at my hotel. He had seen it at Cambridge

and had come with Gide to my studio in Fitzroy

Street on one occasion. I arranged to meet him

on the terrasse of the Cafe Parnasse and waited for

some time. Presently I saw Gide by himself walking

by. He waved to me and carne and sat beside me.

I said, " Where is Marc? "

He said that he did not

know, but as he had nothing to do for an hour or

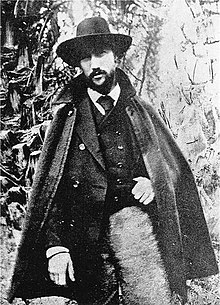

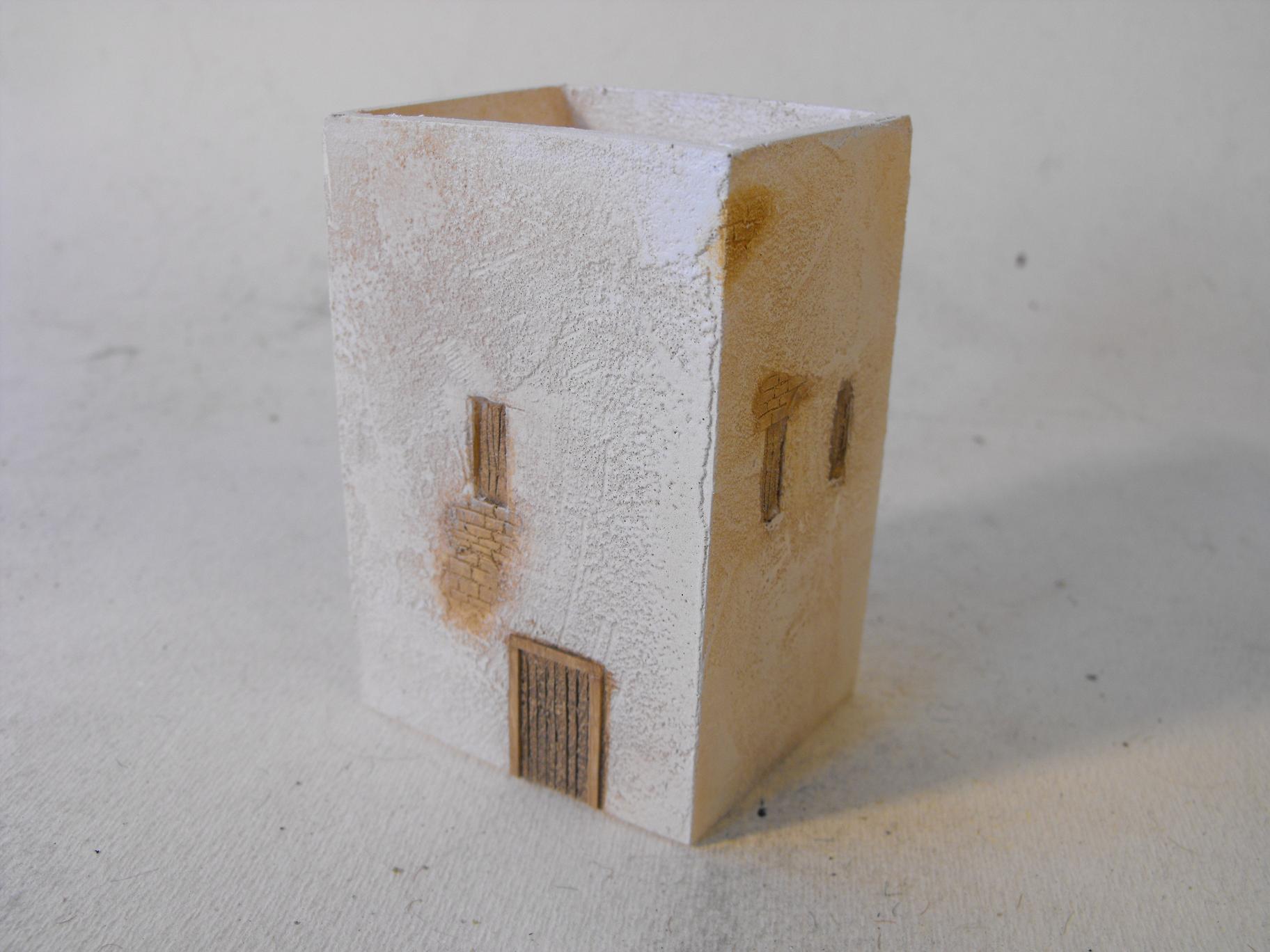

above hamnett by foujita

two, could he come himself and see my pictures.

We went back to my room and he liked some of my

drawings very much. Seeing my guitar hanging on

the wall he asked me to sing some English songs,

and I spent the whole afternoon singing to him.

He was a charming man, elderly, very good-looking

and very amusing. I was very pleased that a man

whose works I admired so much should spend the

afternoon listening to my silly songs and enjoy

himself.

I found a girl whom I had known in London, in

fact she had been at Brangwyns with me and had

married a very nice man who was in some govern

ment service in Paris. I had known him in London

slightly. She did coloured dry points of people and

made a lot of money. She had to go to England

for a few days to see her children who were at

school. She said, " Take my husband out and keep

him from being bored/ This, I think, was the time

of Mardi Gras, and there were several holidays.

We spent Sunday at the Rotonde drinking Vouvray

with some friends, and he asked me to meet him

there again on Monday and we would go to Font-

ainebleau, have lunch there, and then walk to

Moret, where there was a little inn where Arnold

Bennett had lived for some years. We decided that

we would drink to his health when we got there and

have dinner. I had never been to Fontainebleau

before and we went to a very nice restaurant and

had lunch and some white wine and started out to

walk through the forest. It was a very hot day and

there was nothing but four or five miles of forest.

We rested by the road-side from time to time and

about six o'clock we got to the inn, very hot and

thirsty. It was about half a mile from Moret itself

and a most charming looking little place. The caf6

had a garden in front of it with some tables and we

sat down and ordered bottles of beer. We were so

thirsty that we drank eight or nine bottles which,

one by one, as we finished them we placed under the

table. We ordered dinner with a whole duck, chose

the wine, and then went for a walk whilst they

cooked it. We sat on the edge of the forest near a

peasant's hut. It was rather damp and marshy.

I had never met mosquitoes before and did not

realize what they were capable of. I began to

scratch my legs, so did my companion. We went

back to the inn and had a magnificent dinner and

drank Arnold Bennett's health again in white and

red wine, then walked to the

station at Moret, got

into a train packed with French bourgeois, and,

being very tired, slept one on each seat, packed like

sardines between the French, until we reached Paris.

The next day my legs were swollen to about twice

their natural size and my friend telephoned to me

at the Rotonde to say that he had to stay in bed as

he couldn't walk at all. I have since been careful

of damp and marshy ground.

The nice Pole who lived in Modigliani's studio

said that I could come and work there if I liked.

The studio consisted of two long workshops, up

many flights of stairs. Gauguin had lived on the

floor below. It was next to the Academic Golorossi.

The house looked as if it were going to fall down at

any moment and one could see the sunlight shining

through a part of the wall. There was a fire-

escape on the wall on the inside of the window.

It was a rope ladder with wooden rungs attached

with an iron hook. No one ever dared to go

down it as we thought that the wall and the house

would probably come down too. I believe Modig-

liani climbed down on one occasion. The studio

was exactly as he had left it, and parts of the

walls had been painted different colours to make

different backgrounds. The staircase was lopsided,

as it had already slipped about two inches from the

wall. I was rather nervous at first about going up

and downstairs, but it seemed to be quite safe. In

the studio underneath lived Ortiz de Zarate, the

South American painter. The Pole and the Arab

sat with me in the evenings at the Cafe Parnasse.

There were many Polish painters there at that time

and they were unanimous in their hatred of E.

who had gone away with my friend and my money.

There was one particularly amusing painter called

Rubezack, who drank wine, sang songs, and made

jokes all day and half the night. The Arab had

a mistress who was a Frenchwoman and was

very jealous of him. I thought him most charm

ing and very good-looking; he seemed to like me

too. Rubezack had a son and had one day to

go out of Paris to a country place to inspect the

school. He came to the cafe and found the Arab and

myself drinking coffee and asked us if we would

accompany him for the afternoon. We took the train

and came to a charming place with a large house,

which was the school. Afterwards we sat in the gar

den

of a cafe and drank Vermouth Cassis, a drink

which eventually goes to the head and is mostly

drunk in France by work-girls and concierges.

There was a swing in the garden and we took turns

on it and behaved in a ridiculously childish way.

134

PARIS REVISITED

We then walked across some fields, took the tram,

and came back to the cafe to find the Arab's mis

tress, not looking too pleased, and the Pole who

lived in Modigliani's studio.

Underneath the Hotel de la Haute Loire^ which

was the hotel I stayed at in 1914, was the Restaurant

Baty. Outside were baskets of oysters stacked up.

Inside, the floor was tiled and covered in sawdust.

Rosalie was still in the Rue Campagne Premiere, in

her restaurant, and wept when Modigliani's name

was mentioned, although, when he was alive, she

threw him out several times a week. This was not

really surprising as he caused a dreadful disturbance

at times. One day I met Blaise Cendras at the

Pamasse. He had only one arm, the other he had

lost in the War. I had read his poetry and admired

his work very much. He was a great friend of

Ferdinand Leger, and they and many more amusing

people ate every day at Baty's. Sometimes they

would sing whilst they ate. They sang snatches

from the Russian Ballets. They were particularly

fond of snatches from " Scheherazade " and " Pe-

trouska." One day, after lunch, an elderly Baroness

came to the restaurant and they decided to go and

see Brancusi, bringing some wine with them. They

took the Baroness with them. She must have been

very beautiful when she was young. She wore a

yellow wig, which she twined round her head. She

still had a fine figure. She asked me to dinner at her

flat. She had several pictures of Henri Rousseau,

the Douanier. She had the " Wedding/' a large

picture with the bride in white in the middle and

the one with the horse-trap and the black dog. I

was thirty at that time and she must have been very

much older. She asked me how old I was and I

said, " Thirty. 53 She said, " How funny, I am only

three years older than you." I had never met

anyone who lied quite to that extent before and was

rather disturbed. I thought that conversation

under those circumstances was going to be difficult,

if not impossible. Evan Morgan came to see her

with me one evening. She told us that we were

both vulgar and common and it nearly ended in a

battle. The day that they all went to Brancusi's

they danced and sang and the Baroness, feeling tired,

asked if she could go upstairs and lie down for a

short time. She did, and then went home. When

Brancusi went to bed he was horrified to find the

Baroness's yellow wig. It was an embarrassing

moment for him. The next day she wrote and

explained that it belonged to her; she said that she

did not, as a rule, wear it, and would he send it back

at once.

I worked at Modigliani's studio with the Pole and

drew at the Academy. I felt rather a fool about my

painting as all the Poles and, in fact, all the painters

painted in very bright colours, and mine still looked

like London fog. I was very happy aiad felt very well

as I always did in Paris. The Pole liked me very

much. He painted portraits and flowers. He was

small and well-built and looked rather like Charlie

Chaplin, whom he imitated very well as he wore a

pair of very baggy corduroy trousers*

LAUGHING TORSO

CHAPTER X THE SOUTH OF FRANCE

THE Pole asked me if I would go to the South of

France, but, he said, " We must get married first. 55

I had to confess that I already had a husband.

After thinking for a time he decided that it really did

not matter very much. It had never occurred to me

that it did. I had to pretend that it was a sacrifice

on my part. The same dealer, who had been in

duced to give Modigliani money, bought my Pole's

pictures from time to time. We went to see him and

his wife. I felt like a jeune fills with her fiancS.

They were pleased and congratulated us both. The

dealer bought some of his pictures and gave him

some money. I sold some drawings for a few

hundred francs, very much less than the money that

he had and we took a third-class train for the South.

I did not ask where we were going to, as I was so

thrilled with the idea of going South that I did not

mind. Two South Americans came with us, too.

One of them was going to Gollioure to stay with

Foujita and his wife. The train was very uncom

fortable. The seats were made of strips of wood

which, when one tried to lie on them, made holes

in one's body. We slept uncomfortably and I leant

against my Pole, who put his arm affectionately

round my waist. When we started from Paris it was

cold and pouring with rain; as we got further

South it got warmer and warmer. The South

Americans and the Pole spoke Spanish. My Pole had

lived for five years in Spain and spoke Spanish like

a Spaniard. I spoke to them in French. We stopped

for ten minutes at Lyons and went into the station

cafe, drank coffee and ate ham sandwiches.

The train got hotter and hotter and the sun shone

from a cloudless blue sky. We saw olive trees and

flowers of all colours, and finally the Pyrenees in the

distance. I thought that I was approaching Para

dise, and began to wonder if I had not died during

the night and had really arrived there. I ached all

over and was getting very hungry. We decided to

stay at Collioure, if we liked the place, and to find

some rooms. In order to get to Gollioure we had to

get off the train at Port Vendres

, the place where

the boats sail for Algiers and Morocco. We arrived

there at eight in the morning, and dragged our

weary bodies to a little cafe on the quays. I had

never seen such blue water and such beautifulfishing-

boats with curved sails. The boats were painted the

brightest of blues, greens, and reds. I looked at

them and wondered however I should paint them;

they were so perfect in themselves that it seemed

impossible to do anything that would not resemble

a coloured photograph. The cafe had melons piled

up outside. We had a bottle of red wine to revive

us, some coarse bread, and butter and cheese. From

Port Vendres we had to walk to Gollioure along the

cliffs for about four miles. There were high moun

tains behind us and as we walked we saw an Arab

castle on the top of a hill. It looked like something

out of the Arabian Nights. At last we turned a corner

and saw a bay, the other side of which was Collioure.

There were pink, green, and white houses and an

LAUGHING TORSO

Arab tower on the sea-shore.

We walked round the

bay and got down to the shore. There was a

stone path at the foot of the old fort and the sea

came right up to the path. The Foujitas had the

best house in Collioure. It was practically on the

sea. There was only a road and a small stretch of

seashore in front of it. Matisse had lived there for

many summers. It had a balcony and several large

rooms. At this time Foujita was living with his

first wife, whom I had not met before. She was

French and had most beautiful legs, but her body

was shapeless and enormous. She had the most

terrifying face I have ever seen and I was frightened

of her. She screamed at Foujita most of the time.

They were very kind and pleased to see us and found

us a charming place in a very narrow street near the

sea. It cost a hundred and fifty francs a month. It,

had a large room, with two windows looking on to

the street, and an alcove at the back which con

tained a bed. There was also another small alcove.

In the front room was a primitive stove which burnt

charcoal. The old lady who rented it to us was very

ugly and had long teeth like a horse. Appar

ently in this part of the world, there is something in

the water which makes people's teeth drop out, and

even the quite young women had teeth missing.

There were no sanitary arrangements of any kind

and a bucket was placed in the Smaller alcove for

my use. The gentlemen of the town walked every

morning up a hill to the moat of the fort. The old

lady and most of her family earned their living by

packing and salting fish, principally sardines.

Under each of the houses in the street were large

cellars in which they packed the fish. The women

dressed in black with black handkerchiefs over their

heads.  Our landlady's sister kept a little shop. She

Our landlady's sister kept a little shop. She

sold everything, including tobacco. She had one

of the most beautiful faces that I have ever seen.

She must have been nearly fifty and wore the black

dress that all the women wore; she moved her

hands most gracefully. She had a beautiful voice

and looked like the Virgin Mary. I asked the land

lady if there were not any photographs of her when

she was young. She said that they never troubled

about anything like that, and that the people for

miles around came to Collioure to look at her and

admire her.

The evening of our arrival Foujita and his wife

asked us to dinner. Foujita was a marvellous cook,

and we all went to the kitchen and helped. It ended

by us all being chased out, as Foujita explained in

Japanese, rather forcibly, that " too many cooks

spoilt the broth We had breakfast in a cafe the

next morning, and afterwards I wandered round the

town with a string bag to visit the shops. I bought

some meat, and some potatoes and onions, and the

Pole and I cooked it. He cooked very well indeed,

and I knew how to do several things quite well. We

had lunch and then went out to view the landscape

to see what we could paint. I was frightened of be

ginning anything, as he painted much better than I

did, but he was very kind and sympathetic, and said

that it did not matter much what I painted, but "

faut travailler" He had been a great friend of

Modigliani's, and knew many stories about him, so

Modigliani's, and knew many stories about him, so

I was never bored for a minute. We went to the

sea-shore every morning with the Foujitas and the

South American. There were bathing-boxes, and

Madame Foujita and I shared one and the men had

another. Foujita swam like a fish and dived

beautifully. I could not swim at all, the result of

my having been " ducked " when I was a child, but

they all decided to teach me. We all made a great

effort and finally after a week, I managed to swim

five metres, and after a scream of triumph, sank.

We went in the evening to a cafe where they had, on

Friday nights, Cafe Concerts. The songs they sang

shocked even me, they were of an unbelievable

indecency, but the population were delighted, and

cheered loudly. I drew at the cafe during the day

time, as we sometimes went there after lunch.

There were Senegalese working near by, digging a

trench. They never appeared to be doing any work,

they just posed in attitudes, resting on their pickaxes

and their shovels, standing in very well composed

groups, never moving at all. We stayed at Collioure

for three months and even then the trench was not

completed. One day my Pole said to one of them,

" How do you like the women here? " And he re

plied, " Not at all, they smell too much

Ap

parently the white girls smelt as badly to them as

the black men did to the white girls, and so no one

had any success at all.

We had brought metres of canvas with us and

some stretchers, and a few days later I found a

motif. It was up a hill; one saw roofs in the fore-

ground and the Arab tower with the sea behind and

a few fishing -boats with white sails, and in the

background a green hill with white waves washing

against the rocks. I saw the painting again the

other day. It is in the collection of Mary Anders.

The white waves were very well painted and so

was the Arab tower. The roofs and the sea I did

not think so highly of, and thought how much

better I could have painted them now. The Pole

was very sweet and encouraging. The Foujitas

suggested that we should take our supper and some

wine to the Arab castle that we had seen on our way

to Gollioure. We started off about four p.m. and

climbed the hill. There had been a drawbridge,

with quite a narrow and small drop, only about two

yards wide and six feet deep. It was quite easy to

jump across it, which I and the Pole did at once,

without a thought. When it came to Mrs. Foujita

she screamed with terror. The Pole and I jumped

back and made her jump, she was in a fainting con

dition by the time she got to the other side. I made

a few sinister remarks in bad taste about education

at the Royal School of Officers 3 Daughters of the

Army, the British Empire, cricket, sport, courage,

etc., which I don't think the poor creature was in

a condition to hear. We revived her with some wine

and walked up the steps inside the castle. The

castle was square outside, but inside there was a

round hole, surrounded by a path. On the stone

floor, at intervals of a few yards, were holes, and

underneath was water, into which enemies were

pushed. We got on to the roof, which was large

LAUGHING TORSO

and flat. The view was magnificent. We sat down

and had our supper of wine, bread, olives and sar

dines : one could never escape at any meal from the

eternal sardine it appeared in every form salted ,

fresh, boiled and fried. Madame Foujita spoke in a

gruff and angry voice, even when she was not

annoyed, but that was not often. Foujita was

angelic and never answered back or said a word.

I don't think that she had ever seen or met an

English person before, and she would sit and gaze

at me in astonishment for hours. The South

American had apparently been very rich once and

was an ex-amour of Madame Foujita's. He had a

face like a hawk and a long thin body that was

rather beautiful and resembled an old ivory Spanish

crucifix. He was very Spanish and talked about

poetry, life, hope, and the soul. The Pole knew a

good deal about Spaniards and laughed at him

sometimes. Madame Foujita suspected me of

laughing at her too, but she was, I am thankful to

say, not quite sure. Foujita painted at home during

the afternoons. He did not use an easel, but placed

a canvas against a chair and sat on the floor with

his legs crossed. He worked with a tiny brush, very

rapidly. The South American sat in the sun, drank

wine, and blinked his eyes.

My Pole and I went out every day to find new

motifs to paint. After a week we saw so many sub

jects that we thought that we would have to stay

there for about seventy years in order to accomplish

them. I tried to paint olive trees. I found them

almost impossible. One day we found a beautiful

motif on a hill. It was very windy, so we attached

our easels to a string and a large stone, so that they

could not move. I was painting furiously, and

suddenly, behind an olive tree, appeared a Japanese.

He said, " Bon jour, Nina" and I looked at him for

a moment and recognized him as the friend of

Foujita Kavashima.  This was quite fantastic as

This was quite fantastic as

one does not expect to see people one has not seen

for ten years on a Pyrenee.

One day we decided to have a picnic in the

woods. We bought sardines, bread, cheese and

some wine. We found a place with very green

grass. I thought at once of mosquitoes we

spread out some paper on the grass. After lunch

the paper was strewn all over the place. I said,

thinking of Hampstead Heath, " We must clean

the paper up. 95 Madame Foujita said, " Pourquoi! "

And I said, " It spoils the landscape, and so I

dug a hole in the ground and buried all the paper

and sardine bones. After lunch Foujita saw a

large tree. It had a big trunk and no branches at

all. He said, " I will climb this tree. I wondered

how he was going to do it. He took the trunk of the

tree with one hand on each side and climbed up

like a monkey. We all looked at him with astonish

ment and admiration. He could use his toes in the

same way that he could use his fingers. To enter

Spain one had to have a visa. None of us had one,

but we wanted very much to get to Port Bou, which

Port Bou, which

is the first Port in Spain. Madame Foujita, although

tiresome at times, was a woman of determined

character, and if she made up her mind to do some-

LAUGHING TORSO

LAUGHING TORSO

thing, nothing, not even the police force, or the

customs officials, could thwart her. We heard that

there was a fete day in Spain. She had a brilliant

idea.

We would take the train to Cerbere, the last

station before Spain, and walk over the Pyrenees

into Spain. Madame Foujita dressed herself up in

her best clothes, with a pair of very high-heeled

patent leather shoes, not forgetting to put in

Foujita's pocket a pair of rope-soled shoes. This I

did not know about when we started and wondered

how she would climb the mountain, which was of

a respectable height. I wore a corduroy land girl's

coat and skirt, with pockets all over it, and looked

extremely British. We got to Cerbere and arrived

at the foot of the mountain. Madame F. took off

the high-heeled shoes, which Foujita put in his

pocket, and put on the rope-soled shoes and we

began to climb the mountain.

About a quarter of

the way up we were stopped by the Customs, who

asked to see our passports. Madame F. took the

situation in hand, and explained in forcible language

that we were not climbing the mountain with a view

to descending the other side into Spain, but only to

admire, from the top, the Spanish scenery. I think

they were so terrified of her that they let us continue.

When we got to the top of the mountain we could see

thirty or forty miles of Spain. This mountain was

not nearly so high as the one that we had climbed

before; so we saw the view much more clearly.

We saw a square hole in the ground, which had some

steps leading downwards. We all walked down and

found a cellar with Spaniards drinking wine out of

bottles with long spouts* They held the spouts to

their lips, opened their throats, and down went the

wine. We ordered a bottle of wine and some glasses.

The Pole and the South American drank out of the

bottles. The French, who were entering Spain,

drank to the health of the Spaniards, and the

Spaniards who were about to enter France, drank

to the health of the French. We drank to every

body's health, including our own, and the Customs

House Officers. We then descended the other side

of the mountain and entered Port Bou. The cafes

were filled. The Spanish men wore black hats and

smoked cigars. When they saw me they screamed,

" Inglese! Inglese! " This, I realized, was regrettable,

but could not be helped. The Spaniards had little

fans, which they flapped all the time. We found a

restaurant and ordered a large lunch with a litre of

Spanish wine. It cost us a good deal of money, as

we had to change our francs into pesetas. The wine

was so strong that even five of us dared not finish the

bottle, which we left only three-quarters empty.

After lunch we visited the fete. There were re

gattas, and dances, and guitars, and what was de

scribed as pigeon-shooting. This rather horrified

me as the unfortunate pigeons were tied to posts

by their legs. The Spaniards shot at them. There

was a whole row of pigeons and if one was wounded

they very rarely killed one outright it flapped its

wings and frightened the other birds. It was then

time to return, as we had our train to catch at

Cerb^re. We passed the Customs, who were tactful

enough not to ask us any questions, and returned to

Collioure.

After two weeks Foujita and his wife had to return

to Paris. We had a letter from a Pole, R., and his

wife, to say that they were coming to Collioure.

They had found an apartment near the port.

Madame R. was very fat and very bourgeoise, and I

thought rather kind. My Pole did not like her very

much. I think the same kind of person, if she had

been English, would have been quite impossible,

but we, being females, and of such different races,

got on very well. At least she was a change from

Madame Foujita. She was always suffering from a

different malady, she had indigestion, rheumatism,

change of life, stomach troubles, headaches, feet that

would not walk, and all kinds of other things. One

day we went to the seashore to bathe. R. very

seldom bathed, because he said that his figure looked

like a "sac de merde" which indeed it did. His wife

had the good sense not to bathe at all. My Pole

bathed with a pair of bathing -drawers, not the.

regulation kind that covers the chest. When he

walked out of his bathing box Madame R. gave a

scream of horror and said, " C'est indecent I " I then

gave another lecture about England and told her

what I thought about her views of morality in very

forcible language. One evening we were sitting in

our cafe, which had a terrasse in front and each side

a small wall about two feet high. It was about six

p.m. and quite light. Suddenly, on the other side of

the wall, a strange figure appeared; he had a black

beard, a cap, and scarf round his neck. He said

something in Spanish and my Pole said, of course,

in French, as he did not speak English, " He speaks

fifteenth-century Spanish." My Pole knew Spanish

literature very well indeed, and answered him, and

they had a conversation. We asked him to have a

drink, but he disappeared behind the wall in the

same way that he had appeared. We never saw him

again. My Pole said to me that it was a drole de

chose, and I agreed with him.

One morning I went out with my string bag to

buy the food for the day. I saw outside the butcher's

a cart full of pigs that had come to be killed. I

thought that perhaps they would kill them in a

slaughter-house and went for a walk to buy butter

and bread. When I came back I saw one pig sitting

outside the butcher's shop with its head on its front

paws, and large tears streaming out of its eyes. I

was told that its brother had been killed in the

street before its eyes and that it was crying. This

sounds a fantastic story. I walked away and told

my Pole. He said that it was true and that pigs

were so like human beings that they wept when they

were unhappy. An hour later I went back to buy

some pork and they gave it to me and it was warm

and I cried too. R., my Pole, and I went for walks

together. Madame R. could not and would not.

We were all glad about this as her only topics of

conversation were her diseases and her troubles.

We walked sometimes to Port Vendres. I sat in

the cafe on the front. There was a very high

mountain behind Collioure. We wanted to climb

it, but heard that it was very much further away

and higher than it looked. I was determined

to do some mountaineering, so we found a nearer

mountain that was only seven hundred metres

high and from the top of which one could see

Spain. We started one afternoon. The first part

was easy, but as we got higher up we had to climb

over rocks, sometimes having to cling on to the

grass and shrubs. We got hot and thirsty and

found a spring. We wished that we had brought

some beer with us. When we reached the top the

view was wonderful. Spain was so entirely different

from France. The whole character of the landscape

was different. On the horizon was a small black

cloud. My Pole said that we must descend as

quickly as possible as, in a very short time, there

would be a terrific storm. Just as we reached the

foot of the mountain the storm broke. I had never

seen such lightning before and we had to take re

fuge in a shop. It was like a large cellar and the

whole floor was stacked with melons. We sat on

the melons, which were very uncomfortable, and

the old lady gave us some wine. The storm went on

for so long that we got bored with waiting and went

home. We had to take the path at the foot of the

fortress, where we had walked on the day we

arrived. The rain came down in torrents and within

a tew seconds we were all dripping. The lightning

struck the sea a few feet from us and I never expected

to get home alive. Our street was a pool of water.

We lit the charcoal fire and were not dry till the

next day.

At least every two weeks there was a fete, when

nobody did any work. A comic band appeared.

They played in a little square. There were four of

them in Catalan costume and they sat on four

barrels. Three of them played curious instruments

like clarionets, but they made an odd noise,, almost

like bagpipes, and the fourth one played a trumpet.

They played one particular tune over and over

again and the peasants danced Catalan dances. I

think that, during one week, there were three fete

days. As we lived near the square and as the band

played till after midnight we found it rather tire

some. We painted one motif in the morning and

another in the afternoon. I found a wonderful

scene with trees and houses. After I had painted

the usual blue sky for two afternoons a storm arose

and the sky became dark blue. I painted as hard

as I could and the painting was getting better and

better and then the downpour started and I had

to run for shelter. Of course, I never finished the

painting as there was not another storm. I always

think that it might have been a masterpiece. I

think one thinks that about every picture one has not

finished. We had painted about fourteen pictures

and the money was getting rather low. We had only

about three weeks 5 money left.

There was a curious old lady who paraded up and

down the streets. She was a beggar and moved

from place to place according to the seasons. She

spent the winter months in Paris. Everyone hated

her because she sang or rather croaked in a loud

and raucous voice. When she walked down our

street all the inhabitants put their heads out of their

windows and aimed at her with the contents of

their pots de chambre.

The grapes were now ripe and the time had come

for the wine to be made. In the street in front of

our door a wine-press was put up. One had to step

over a part of it in order to get out. This continued

for about a week and the wine-press was removed.

One morning I went out with my string bag to buy

the lunch and was hailed by our landlady. She

asked me to come and taste the newly-made wine.

I went into her cellar where she packed the fish. I

met her beautiful sister coming up the stairs smelling

very strongly of sardines. It seemed to me odd to

find a woman, who looked so like the Virgin Mary,

smelling of fish. I went into the cellar, where I

found my landlady, who had lost another tooth,

surrounded by all her relatives, tasting the new

wine. I joined them. It was rather raw, but gave

one a pleasant feeling of amiability. When I left

I met, in the street, another neighbour, who also

invited me to taste her wine. I could not possibly

refuse and had some white wine. On emerging I

found still another neighbour and had to repeat the

process. I then arrived home without any lunch at

all and fell sound asleep. My Pole was very kind

and sympathetic and forgave my abominable be

haviour.

The patron of the caf< we frequented was a

charming man and now and then bought us drinks.

(Madame R. had already left for Paris.) When

he heard we were leaving he asked us to have

a Catalan breakfast. He said that we must arrive

at eight a.m. Breakfast consisted of a huge dish of

anchovies, swimming in oil and garlic, sausages,

olives, black and white bread, and first white wine

and then red. There were three bottles of white

wine and three of red and four of us to drink them.

At nine-thirty we left. My Pole, R., and I decided

that the only thing for us to do was to take a long

walk. We walked silently for about three miles

when we came to the sea-shore where we lay down

in a row on the pebbles and slept. There was, of

course, no question of the tide coming in or going

out as there is practically no tide at all in the

Mediterranean and some hours later we woke up

feeling rather worse and smelling horribly of garlic.

I have never since really appreciated either ancho

vies or garlic and hope that I shall not again have

to experience a Catalan breakfast. We had by now

just the railway fare back to Paris.

CHAPTER XI BACK TO PARIS AND TO CELEBRITIES

I WENT to Modigliani's studio and stayed with the

Pole. It was very uncomfortable but I did not mind

as I was quite used to discomfort. My Pole sold

some pictures to the dealer and a collector, so we

had a little money to live on. We had a large coke

stove on which we cooked. There was no gas or

electric light., so we had an oil lamp. In the morn

ings the Pole cleaned and filled the lamp, and in the

evenings we read the French classics, sitting one

each side of Modigliani's old and scarred table.

The picture-dealer had a spare copy of Modigliani's

death mask. There were, I think, four taken. It

was rather horrible as his mouth had not been

bound up and his jaw dropped. It looked terrifying

through the door of the first workshop in the shadow.

We felt that we had to keep it with us, because if we

put it out or gave it away it would be a breach of

friendship. The Arab came and spent the evenings

with us. Sometimes we got a bottle of cheap wine

and talked about Montparnasse before the War.

The painter who lived downstairs came to see us

sometimes too. In the summer he became very

eccentric and did the most odd things. The first

thing he would do was to break the lock of his studio

door. One night we came home from the Cafe

Parnasse about midnight and found his door wide

open. In front of the door, on an easel, was a

painting of an enormous eye. It was done in great

detail and was about two feet wide and a foot high.

BACK TO PARIS AND CELEBRITIES

He was not in. We did not know what to do, so we

closed the door. We were quite certain that Modig-

liani was still with us and fancied at night that we

could hear his footsteps walking through the studio.

It was certainly a most sinister place.

We worked during the daytime. I painted Still

Life and worked at the Academy from the nude in

the afternoon. We did a great deal of work. We

had a tabby cat. Once we were all very broke,

myself., the Pole, and the Arab. For three days we

could not find a penny, we did not mind much about

ourselves, but we were so sorry for the cat, who had

to starve also. We had a lot of Modigliani's books

and in despair the Pole took one on philosophy and

read it to us. As he turned over the pages he sud

denly came to a HUNDRED FRANC NOTE.

Modigliani's wife used to hide money away from him

and this was one of his notes. We were so delighted

that we rushed into the nearest workmen's restaur

ant, taking the cat with us, and ate and drank to

Modigliani's health the whole evening. The poor

cat ended in a very tragic way. One evening we

were reading and the cat began to run round in

circles. We realized that it had gone mad so we

locked it up in the lavatory and went out. We dared

not come home until the next morning. We sat in

cafe all night and at eight in the morning came

home to find an apparently dead cat. We went to

bed as we were very tired and suddenly heard a most

dreadful howl. We opened the door of the lava

tory and found that the cat was really dead. The

next thing to do was to dispose of the body. We

decided that we could not put our poor friend in

the dustbin so we sat down and thought. In the

gutters of the streets of Paris are, at intervals,

small slits about a foot and a half long and about

six inches high. These lead to the sewers of Paris,

which lead to the Seine. We decided that at

night we would wrap our cat's body up and drop

him down, and he might eventually float down to

the sea, I thought of Alfred Jarry's remark about

dead people. I think it is in the Docteur Faustrol; I

can't quote it in French, but when he asks, " What

is the difference between live people and the dead? "

the answer is, " The live ones can swim both up

and down the river, but the dead ones can only

swim down. We stretched our cat out straight and

wrapped him in two layers of paper and tied him up

with string. We made a handle of the string and he

looked rather like a parcel containing a long bottle.

At nine in the evening we went out, the Pole holding

the parcel by the string handle. We crept round

the neighbourhood, looking for a quiet spot. We

walked for some time round the Luxembourg

gardens and finally found a suitable place in the

Rue d'Assas. Both crying bitterly, we popped him

in and then went to the Gaf<6 Parnasse, and had

some drinks. Everyone asked why we were so sad,

but we did not tell them, and went home to bed.

The Pole knew many Spaniards and they came

to our studio and played and sang. . . , They were

much the same as the South American. I liked the

Spaniards. They seemed to spend their lives playing

guitars. Even so they really did a great deal of work.

at the chic of the French women.

and I asked who she could

came up to the Cafe Parnasse, which has now be

Our landlady's sister kept a little shop. She

Modigliani's, and knew many stories about him, so

This was quite fantastic as

Port Bou, which

LAUGHING TORSO

A labour of love. Amazing pictures

ReplyDelete