I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow,

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infant’s cry of fear,

In every voice, in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear.

How the Chimney-sweeper’s cry

Every black’ning Church appalls;

And the hapless Soldier’s sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls.

But most thro’ midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlot’s curse

Blasts the new born Infant’s tear,

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.

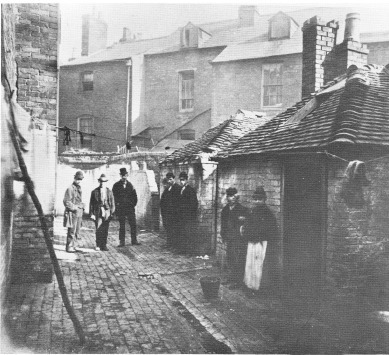

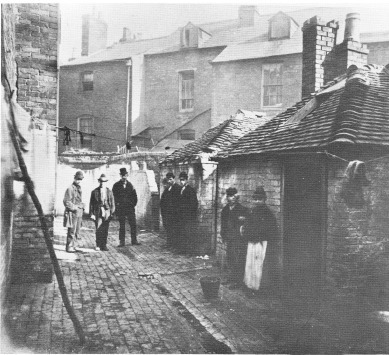

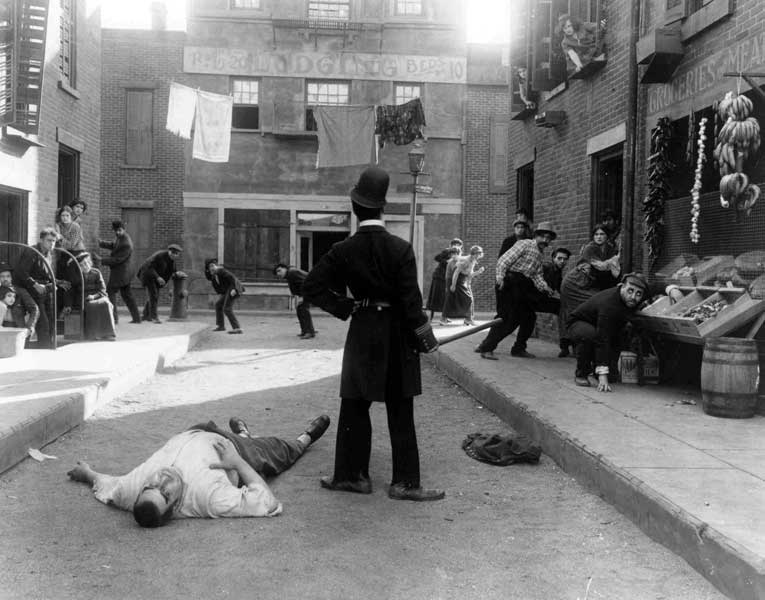

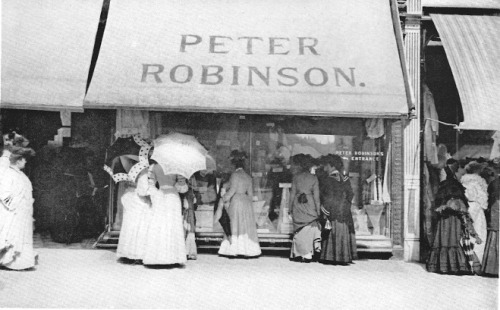

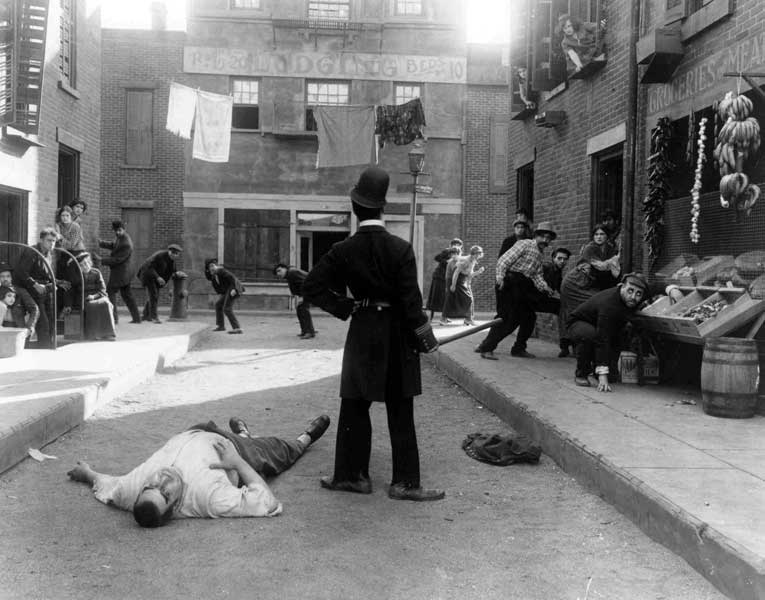

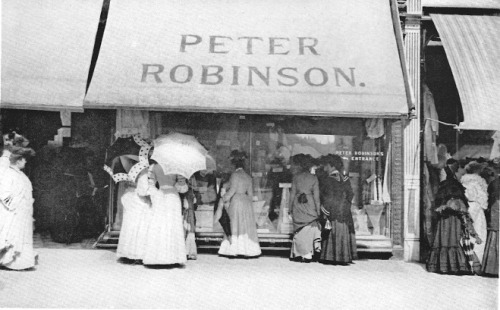

Above Ripper Street, watch at all costs

1888 was a bad year to be a prostitute. Between August 7 and November 10 of that year, five women were killed in the Whitechapel district of London's East End, their throats slashed and their bodies mutilated in a way that indicated they all met their fates at the hands of the same person. The law's failure to identify the killer led to such an outcry that both the home secretary and London police commissioner resigned in disgrace.as the killings died away a man of hope and joy was born.

This man was believed to have been born on April 16, 1889 in East Street, Walworth, south London – ironically just four days before the birth of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, whom he lampooned in his classic 1940 film The Great Dictator.

– ironically just four days before the birth of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, whom he lampooned in his classic 1940 film The Great Dictator.

Chaplin's previously secret MI5 files show that security officials were concerned about whether to advise prominent figures in Britain to avoid meeting the comic actor. Spencer Chaplin was born on 16 April 1889 to Hannah Chaplin (née Hill, 1865–1928) and Charles Chaplin, Sr. (1863–1901). There is no official record of his birth, although Chaplin believed he was born at East Street,

(née Hill, 1865–1928) and Charles Chaplin, Sr. (1863–1901). There is no official record of his birth, although Chaplin believed he was born at East Street,  , in South London.His mother and father had married four years previously, at which time Chaplin, Sr. became the legal carer of Hannah's illegitimate son, Sydney John

, in South London.His mother and father had married four years previously, at which time Chaplin, Sr. became the legal carer of Hannah's illegitimate son, Sydney John (1885–1965).Sid Chaplin's most important contribution to history is in the field of aviation. In May 1919, he, along with pilot Emery Rogers, formulated the first privately owned domestic American airline, the Syd Chaplin Airline Company, based in Santa Monica

(1885–1965).Sid Chaplin's most important contribution to history is in the field of aviation. In May 1919, he, along with pilot Emery Rogers, formulated the first privately owned domestic American airline, the Syd Chaplin Airline Company, based in Santa Monica , California. Even though the corporation lasted only a year, in that time it accumulated many "firsts." Syd and partners had the first ever aeroplane showroom for their Curtiss aeroplanes.

, California. Even though the corporation lasted only a year, in that time it accumulated many "firsts." Syd and partners had the first ever aeroplane showroom for their Curtiss aeroplanes.  Rogers conducted the first roundtrip Los Angeles toSan Francisco flight in one 24-hour period. Charlie Chaplin took his first-ever aeroplane flight in one of Syd's planes, as did many other notable personages of the period. Chaplin got out of the aviation business right after legislation began to pass regarding pilot licensing and the taxation of planes and flights.At the time of his birth, Chaplin's parents were both entertainers in the music hall tradition; Hannah, the daughter of a shoemaker,had a brief and unsuccessful career under the stage name Lily Harley, while Charles Sr., a butcher's son, worked as a popular singer. The Chaplins became estranged around 1891; a year later, Hannah gave birth to a third son—George Wheeler Dryden

Rogers conducted the first roundtrip Los Angeles toSan Francisco flight in one 24-hour period. Charlie Chaplin took his first-ever aeroplane flight in one of Syd's planes, as did many other notable personages of the period. Chaplin got out of the aviation business right after legislation began to pass regarding pilot licensing and the taxation of planes and flights.At the time of his birth, Chaplin's parents were both entertainers in the music hall tradition; Hannah, the daughter of a shoemaker,had a brief and unsuccessful career under the stage name Lily Harley, while Charles Sr., a butcher's son, worked as a popular singer. The Chaplins became estranged around 1891; a year later, Hannah gave birth to a third son—George Wheeler Dryden —fathered by music hall entertainerLeo Dryden. The child was taken by Dryden at six months old, and did not re-enter Chaplin's life for 30 years

—fathered by music hall entertainerLeo Dryden. The child was taken by Dryden at six months old, and did not re-enter Chaplin's life for 30 years

1888 was a bad year to be a prostitute. Between August 7 and November 10 of that year, five women were killed in the Whitechapel district of London's East End, their throats slashed and their bodies mutilated in a way that indicated they all met their fates at the hands of the same person. The law's failure to identify the killer led to such an outcry that both the home secretary and London police commissioner resigned in disgrace.as the killings died away a man of hope and joy was born.

This man was believed to have been born on April 16, 1889 in East Street, Walworth, south London

– ironically just four days before the birth of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, whom he lampooned in his classic 1940 film The Great Dictator.

– ironically just four days before the birth of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler, whom he lampooned in his classic 1940 film The Great Dictator.

MI5 searched through files in London for his birth certificate, including checks for his supposed alias "Israel Thornstein".

But the previously secret records show that agents concluded: "It would seem that Chaplin was either not born in this country or that his name at birth was other than those mentioned."

John Marriott, then head of MI5's counter-subversion branch, was not convinced that the absence of a birth certificate was a matter of concern for the intelligence services.

He wrote: "It is curious that we can find no record of Chaplin's birth, but I scarcely think that this is of any security significance."

Police investigators from Scotland Yard's Special Branch added to the intrigue by passing on a tip-off from a source who claimed the actor was born near Fontainebleau,  of Paris.

of Paris.

of Paris.

of Paris.A police memo to MI5 noted: "There may or may not be some truth in this, but in view of the fact  that no documentary proof has been obtained that Chaplin was born in the United Kingdom, it may well be that he was in fact born in France."

that no documentary proof has been obtained that Chaplin was born in the United Kingdom, it may well be that he was in fact born in France."

that no documentary proof has been obtained that Chaplin was born in the United Kingdom, it may well be that he was in fact born in France."

that no documentary proof has been obtained that Chaplin was born in the United Kingdom, it may well be that he was in fact born in France."

The case was handed over to MI6, Britain's foreign intelligence service, but it found no trace of Chaplin's birth in either Fontainebleau or nearby mellun

Chaplin's previously secret MI5 files show that security officials were concerned about whether to advise prominent figures in Britain to avoid meeting the comic actor. Spencer Chaplin was born on 16 April 1889 to Hannah Chaplin

(née Hill, 1865–1928) and Charles Chaplin, Sr. (1863–1901). There is no official record of his birth, although Chaplin believed he was born at East Street,

(née Hill, 1865–1928) and Charles Chaplin, Sr. (1863–1901). There is no official record of his birth, although Chaplin believed he was born at East Street,  , in South London.His mother and father had married four years previously, at which time Chaplin, Sr. became the legal carer of Hannah's illegitimate son, Sydney John

, in South London.His mother and father had married four years previously, at which time Chaplin, Sr. became the legal carer of Hannah's illegitimate son, Sydney John (1885–1965).Sid Chaplin's most important contribution to history is in the field of aviation. In May 1919, he, along with pilot Emery Rogers, formulated the first privately owned domestic American airline, the Syd Chaplin Airline Company, based in Santa Monica

(1885–1965).Sid Chaplin's most important contribution to history is in the field of aviation. In May 1919, he, along with pilot Emery Rogers, formulated the first privately owned domestic American airline, the Syd Chaplin Airline Company, based in Santa Monica , California. Even though the corporation lasted only a year, in that time it accumulated many "firsts." Syd and partners had the first ever aeroplane showroom for their Curtiss aeroplanes.

, California. Even though the corporation lasted only a year, in that time it accumulated many "firsts." Syd and partners had the first ever aeroplane showroom for their Curtiss aeroplanes.  Rogers conducted the first roundtrip Los Angeles toSan Francisco flight in one 24-hour period. Charlie Chaplin took his first-ever aeroplane flight in one of Syd's planes, as did many other notable personages of the period. Chaplin got out of the aviation business right after legislation began to pass regarding pilot licensing and the taxation of planes and flights.At the time of his birth, Chaplin's parents were both entertainers in the music hall tradition; Hannah, the daughter of a shoemaker,had a brief and unsuccessful career under the stage name Lily Harley, while Charles Sr., a butcher's son, worked as a popular singer. The Chaplins became estranged around 1891; a year later, Hannah gave birth to a third son—George Wheeler Dryden

Rogers conducted the first roundtrip Los Angeles toSan Francisco flight in one 24-hour period. Charlie Chaplin took his first-ever aeroplane flight in one of Syd's planes, as did many other notable personages of the period. Chaplin got out of the aviation business right after legislation began to pass regarding pilot licensing and the taxation of planes and flights.At the time of his birth, Chaplin's parents were both entertainers in the music hall tradition; Hannah, the daughter of a shoemaker,had a brief and unsuccessful career under the stage name Lily Harley, while Charles Sr., a butcher's son, worked as a popular singer. The Chaplins became estranged around 1891; a year later, Hannah gave birth to a third son—George Wheeler Dryden —fathered by music hall entertainerLeo Dryden. The child was taken by Dryden at six months old, and did not re-enter Chaplin's life for 30 years

—fathered by music hall entertainerLeo Dryden. The child was taken by Dryden at six months old, and did not re-enter Chaplin's life for 30 years

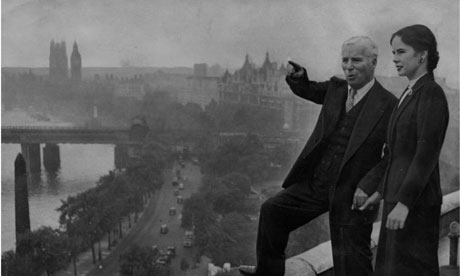

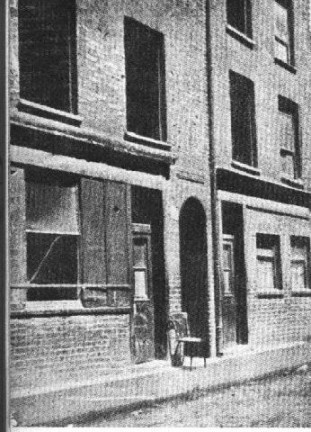

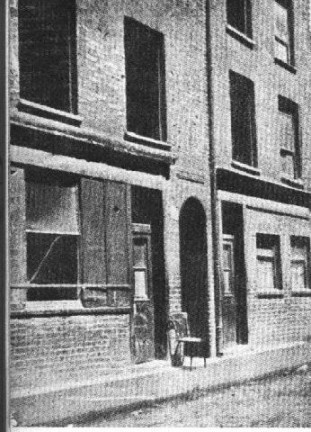

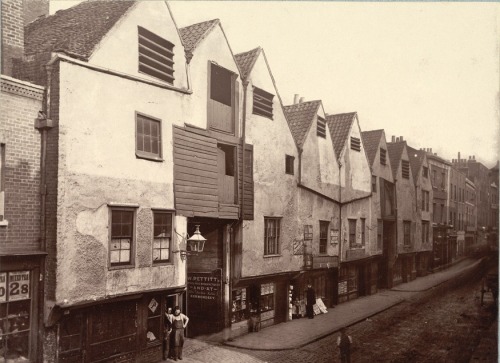

Chaplin home in London

I always thought of Charlie Chaplin as the one who carried a certain culture of the penniless, the ragged and the downtrodden from Europe across the Atlantic, translating it with such superlative success into an infinite capacity for hope, humour and resourcefulness in America.

translating it with such superlative success into an infinite capacity for hope, humour and resourcefulness in America.

I always thought of Charlie Chaplin as the one who carried a certain culture of the penniless, the ragged and the downtrodden from Europe across the Atlantic,

translating it with such superlative success into an infinite capacity for hope, humour and resourcefulness in America.

translating it with such superlative success into an infinite capacity for hope, humour and resourcefulness in America.

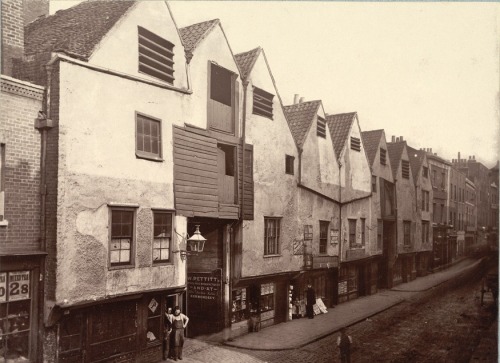

For centuries, Spitalfields has offered a refuge to the homeless and the dispossessed, so it makes sense that the most famous tramp of all time should have known this place.

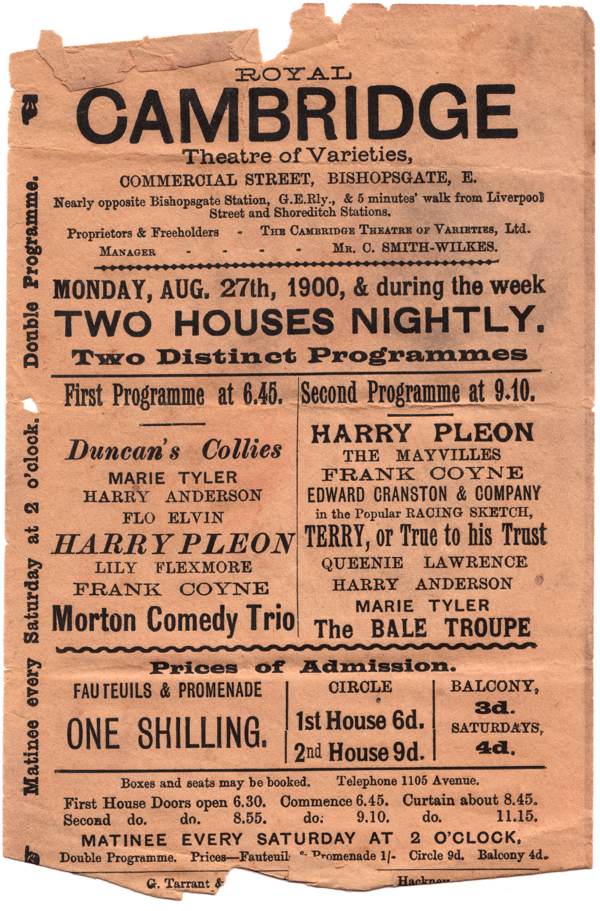

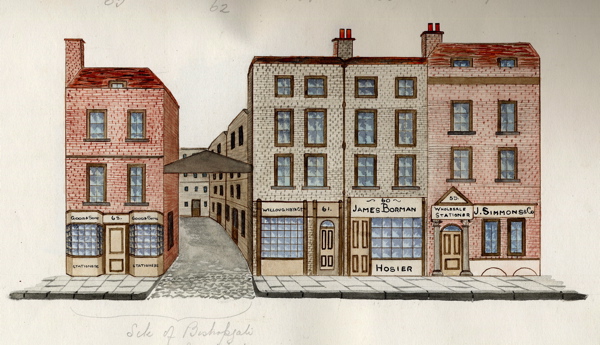

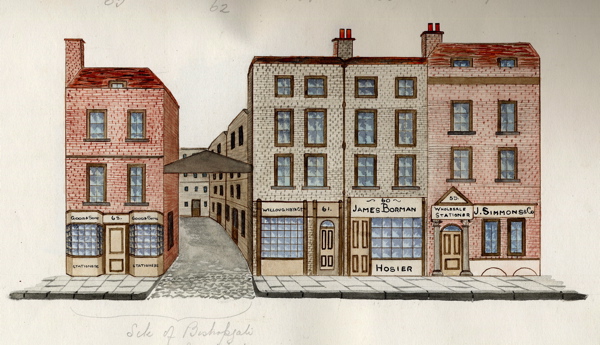

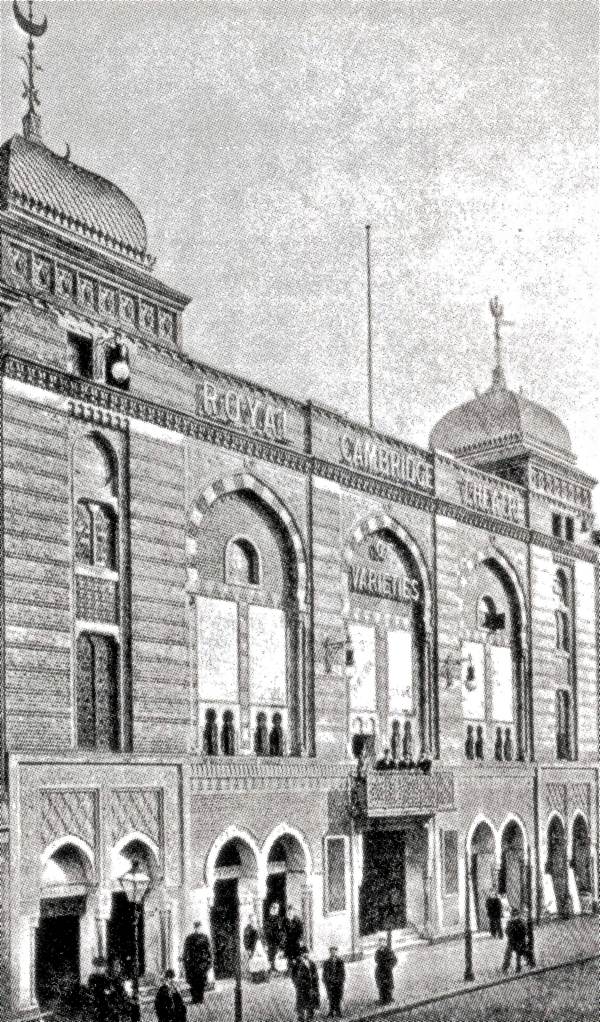

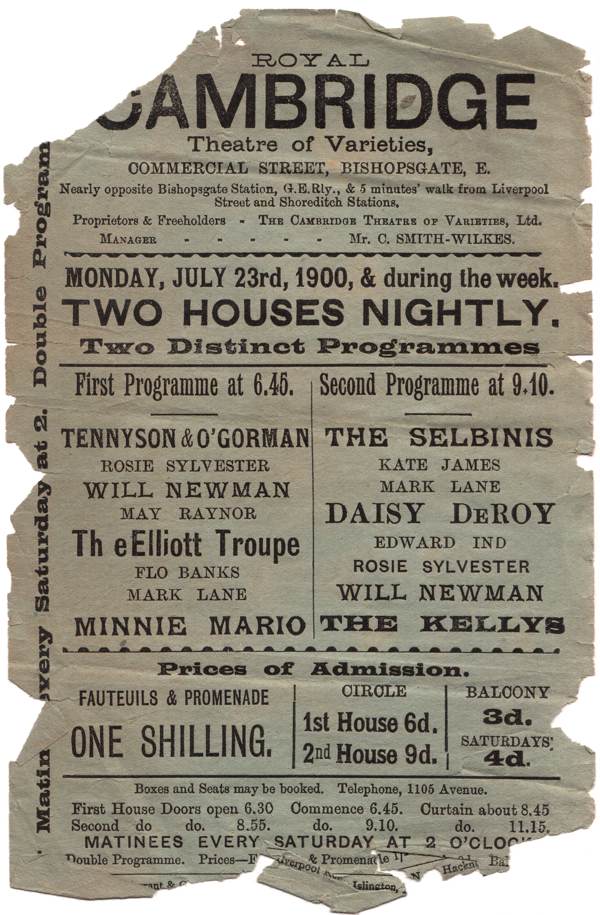

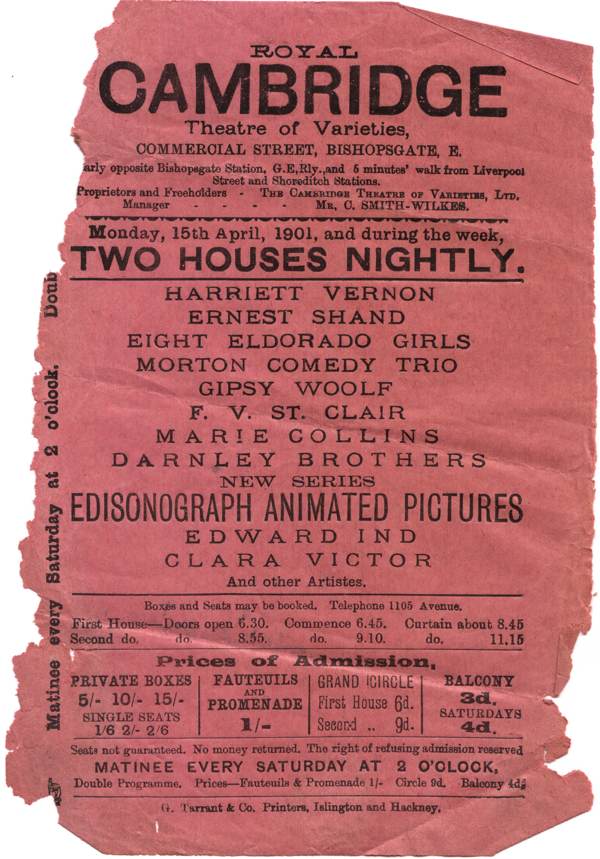

Last year, Vivian Betts who grew up in The Primrose in Bishopsgate g found a handful of playbills that had been in the pub as long as she remembered and which she took with her when they left in 1974 before the building was demolished.

g found a handful of playbills that had been in the pub as long as she remembered and which she took with her when they left in 1974 before the building was demolished.  These bills were for the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in Commercial St.

These bills were for the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in Commercial St.  in 1864, this vast two thousand seater

in 1864, this vast two thousand seater

theatre with a bar capacity of another thousand must have once presented a dramatic counterpoint to the church on the other side of the Spitalfields Market.

theatre with a bar capacity of another thousand must have once presented a dramatic counterpoint to the church on the other side of the Spitalfields Market.  in the nineteenth century, it was one among many theatres in the immediate vicinity, in the days when the East

in the nineteenth century, it was one among many theatres in the immediate vicinity, in the days when the East End could match the West End for theatre and night life.

End could match the West End for theatre and night life.![The country is currently riding the wave of Olympic fever, and in the East End of London the world’s finest athletes go daily into battle for the prize that has so long been held in such high esteem by man; namely, gold. But the Olympics will not be here forever, and much has been said about the legacy the Olympics will leave behind it for the historically poor end ofLondon. Many claim the area will be forever rejuvenated, and I hope so. These were the thoughts that struck me as I read the following passage from Jack London’s excellent 1902 piece of ‘slumming’ journalism, ‘The People of the Abyss’: …I rented no rooms, but returned to my own Johnny Upright’s street. What with my wife, and babies, and lodgers, and the various cubby-holes into which I had fitted them, my mind’s eye had become narrow-angled, and I could not quite take in all of my own room at once. The immensity of it was awe-inspiring. Could this be the room I had rented for six shillings a week? Impossible! But my landlady, knocking at the door to learn if I were comfortable, dispelled my doubts. “Oh yes, sir,” she said, in reply to a question. “This street is the very last. All the other streets were like this eight or ten years ago, and all the people were very respectable. But the others have driven our kind out. Those in this street are the only ones left. It’s shocking, sir!” And then she explained the process of saturation, by which the rental value of a neighbourhood went up, while its tone went down. “You see, sir, our kind [English upper-working class – Ed] are not used to crowding in the way the others do. We need more room. The others, the foreigners and lower-class people, can get five and six families into this house, where we only get one. So they can pay more rent for the house than we can afford. It is shocking, sir; and just to think, only a few years ago all this neighbourhood was just as nice as it could be.” I looked at her. Here was a woman, of the finest grade of the English working-class, with numerous evidences of refinement, being slowly engulfed by that noisome and rotten tide of humanity which the powers that be are pouring eastward out ofLondonTown. Bank, factory, hotel, and office building must go up, and the city poor folk are a nomadic breed; so they migrate eastward, wave upon wave, saturating and degrading neighbourhood by neighbourhood, driving the better class of workers before them to pioneer, on the rim of the city, or dragging them down, if not in the first generation, surely in the second and third. It is only a question of months when Johnny Upright’s street must go. He realises it himself. “In a couple of years,” he says, “my lease expires. My landlord is one of our kind. He has not put up the rent on any of his houses here, and this has enabled us to stay. But any day he may sell, or any day he may die, which is the same thing so far as we are concerned. The house is bought by a money breeder, who builds a sweat shop on the patch of ground at the rear where my grapevine is, adds to the house, and rents it a room to a family. There you are, and Johnny Upright’s gone!” And truly I saw Johnny Upright, and his good wife and fair daughters, and frowzy slavey, like so many ghosts flitting eastward through the gloom, the monster city roaring at their heels. But Johnny Upright is not alone in his flitting. Far, far out, on the fringe of the city, live the small business men, little managers, and successful clerks. They dwell in cottages and semi-detached villas, with bits of flower garden, and elbow room, and breathing space. They inflate themselves with pride, and throw out their chests when they contemplate the Abyss from which they have escaped, and they thank God that they are not as other men. And lo! down upon them comes Johnny Upright and the monster city at his heels. Tenements spring up like magic, gardens are built upon, villas are divided and subdivided into many dwellings, and the black night ofLondonsettles down in a greasy pall. American writer Jack London was twenty-six when he wrote ‘The People of the Abyss’ in which he spends three weeks living as a pauper in the East End of London, a vast “killing machine” of chronic starvation, vermin infestation and overcrowding, in order to present the true face of poverty in the worlds richest and most powerful city. Those days, thankfully, are well and truly over.](http://24.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m8dotfSuVM1r4z2kco1_400.jpg)

g found a handful of playbills that had been in the pub as long as she remembered and which she took with her when they left in 1974 before the building was demolished.

g found a handful of playbills that had been in the pub as long as she remembered and which she took with her when they left in 1974 before the building was demolished.  These bills were for the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in Commercial St.

These bills were for the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in Commercial St.  in 1864, this vast two thousand seater

in 1864, this vast two thousand seater theatre with a bar capacity of another thousand must have once presented a dramatic counterpoint to the church on the other side of the Spitalfields Market.

theatre with a bar capacity of another thousand must have once presented a dramatic counterpoint to the church on the other side of the Spitalfields Market.  in the nineteenth century, it was one among many theatres in the immediate vicinity, in the days when the East

in the nineteenth century, it was one among many theatres in the immediate vicinity, in the days when the East End could match the West End for theatre and night life.

End could match the West End for theatre and night life.![The country is currently riding the wave of Olympic fever, and in the East End of London the world’s finest athletes go daily into battle for the prize that has so long been held in such high esteem by man; namely, gold. But the Olympics will not be here forever, and much has been said about the legacy the Olympics will leave behind it for the historically poor end ofLondon. Many claim the area will be forever rejuvenated, and I hope so. These were the thoughts that struck me as I read the following passage from Jack London’s excellent 1902 piece of ‘slumming’ journalism, ‘The People of the Abyss’: …I rented no rooms, but returned to my own Johnny Upright’s street. What with my wife, and babies, and lodgers, and the various cubby-holes into which I had fitted them, my mind’s eye had become narrow-angled, and I could not quite take in all of my own room at once. The immensity of it was awe-inspiring. Could this be the room I had rented for six shillings a week? Impossible! But my landlady, knocking at the door to learn if I were comfortable, dispelled my doubts. “Oh yes, sir,” she said, in reply to a question. “This street is the very last. All the other streets were like this eight or ten years ago, and all the people were very respectable. But the others have driven our kind out. Those in this street are the only ones left. It’s shocking, sir!” And then she explained the process of saturation, by which the rental value of a neighbourhood went up, while its tone went down. “You see, sir, our kind [English upper-working class – Ed] are not used to crowding in the way the others do. We need more room. The others, the foreigners and lower-class people, can get five and six families into this house, where we only get one. So they can pay more rent for the house than we can afford. It is shocking, sir; and just to think, only a few years ago all this neighbourhood was just as nice as it could be.” I looked at her. Here was a woman, of the finest grade of the English working-class, with numerous evidences of refinement, being slowly engulfed by that noisome and rotten tide of humanity which the powers that be are pouring eastward out ofLondonTown. Bank, factory, hotel, and office building must go up, and the city poor folk are a nomadic breed; so they migrate eastward, wave upon wave, saturating and degrading neighbourhood by neighbourhood, driving the better class of workers before them to pioneer, on the rim of the city, or dragging them down, if not in the first generation, surely in the second and third. It is only a question of months when Johnny Upright’s street must go. He realises it himself. “In a couple of years,” he says, “my lease expires. My landlord is one of our kind. He has not put up the rent on any of his houses here, and this has enabled us to stay. But any day he may sell, or any day he may die, which is the same thing so far as we are concerned. The house is bought by a money breeder, who builds a sweat shop on the patch of ground at the rear where my grapevine is, adds to the house, and rents it a room to a family. There you are, and Johnny Upright’s gone!” And truly I saw Johnny Upright, and his good wife and fair daughters, and frowzy slavey, like so many ghosts flitting eastward through the gloom, the monster city roaring at their heels. But Johnny Upright is not alone in his flitting. Far, far out, on the fringe of the city, live the small business men, little managers, and successful clerks. They dwell in cottages and semi-detached villas, with bits of flower garden, and elbow room, and breathing space. They inflate themselves with pride, and throw out their chests when they contemplate the Abyss from which they have escaped, and they thank God that they are not as other men. And lo! down upon them comes Johnny Upright and the monster city at his heels. Tenements spring up like magic, gardens are built upon, villas are divided and subdivided into many dwellings, and the black night ofLondonsettles down in a greasy pall. American writer Jack London was twenty-six when he wrote ‘The People of the Abyss’ in which he spends three weeks living as a pauper in the East End of London, a vast “killing machine” of chronic starvation, vermin infestation and overcrowding, in order to present the true face of poverty in the worlds richest and most powerful city. Those days, thankfully, are well and truly over.](http://24.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m8dotfSuVM1r4z2kco1_400.jpg)

The ten-year-old Chaplin performed here as one of The Eight Lancashire Lads, a juvenile clog dance troupe, on  Tuesday 24th October 1899 as part of the First Anniversary

Tuesday 24th October 1899 as part of the First Anniversary Benefit Performance, celebrating the reopening of the theatre a year earlier, after a fire that had destroyed it in 1896.

Benefit Performance, celebrating the reopening of the theatre a year earlier, after a fire that had destroyed it in 1896.

Tuesday 24th October 1899 as part of the First Anniversary

Tuesday 24th October 1899 as part of the First Anniversary Benefit Performance, celebrating the reopening of the theatre a year earlier, after a fire that had destroyed it in 1896.

Benefit Performance, celebrating the reopening of the theatre a year earlier, after a fire that had destroyed it in 1896.

Before he died, Chaplin’s alcoholic father signed up his son at the age of eight, in November 1898, with his friend William Jackson who managed The Eight Lancashire Lads, in return for the boy’s board and lodgings and a payment of half a crown a week to Chaplin’s mother Hannah.  The engagement took Chaplin away from his pitiful London childhood and from his mother who had struggled to support him and his elder brother Sydney on her own, existing at the edge of mental illness while moving the family in and out of a succession of rented rooms until her younger son ended up in the workhouse at seven.

The engagement took Chaplin away from his pitiful London childhood and from his mother who had struggled to support him and his elder brother Sydney on her own, existing at the edge of mental illness while moving the family in and out of a succession of rented rooms until her younger son ended up in the workhouse at seven.

The engagement took Chaplin away from his pitiful London childhood and from his mother who had struggled to support him and his elder brother Sydney on her own, existing at the edge of mental illness while moving the family in and out of a succession of rented rooms until her younger son ended up in the workhouse at seven.

The engagement took Chaplin away from his pitiful London childhood and from his mother who had struggled to support him and his elder brother Sydney on her own, existing at the edge of mental illness while moving the family in and out of a succession of rented rooms until her younger son ended up in the workhouse at seven.

st olaves

“After practising for eight weeks, I was eligible to dance with the troupe. But now that I was past eight years old, I had lost my assurance and confronting the audience for the first time gave me stage fright. I could hardly move my legs. It was weeks before I could do a solo dance as the rest of them did.”  Chaplin wrote of joining The Eight Lancashire Lads with whom he made his debut in Babes in the Wood, on Boxing Day 1898 at the Theatre Royal, Manchester.“My memory of this period goes in and out of focus,” he admitted later, “The outstanding impression was of a quagmire of miserable circumstances.”

Chaplin wrote of joining The Eight Lancashire Lads with whom he made his debut in Babes in the Wood, on Boxing Day 1898 at the Theatre Royal, Manchester.“My memory of this period goes in and out of focus,” he admitted later, “The outstanding impression was of a quagmire of miserable circumstances.”

Chaplin wrote of joining The Eight Lancashire Lads with whom he made his debut in Babes in the Wood, on Boxing Day 1898 at the Theatre Royal, Manchester.“My memory of this period goes in and out of focus,” he admitted later, “The outstanding impression was of a quagmire of miserable circumstances.”

Chaplin wrote of joining The Eight Lancashire Lads with whom he made his debut in Babes in the Wood, on Boxing Day 1898 at the Theatre Royal, Manchester.“My memory of this period goes in and out of focus,” he admitted later, “The outstanding impression was of a quagmire of miserable circumstances.”

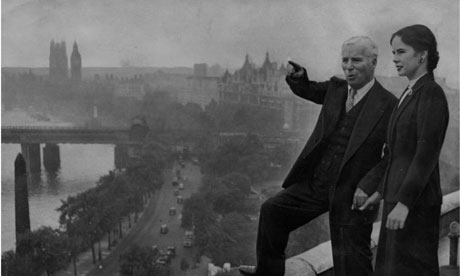

above the bedford

Yet Chaplin’s experience touring Britain when Music Hall was at its peak of popularity proved both a great adventure and an unparalleled schooling in the method, technique and discipline that every performer requires to hold an audience. “Audiences like The Eight Lancashire Lads because, as Mr Jackson said, we were so unlike theatrical children. It was his boast that we never wore grease paint and our rosy cheeks were natural. If some of us looked a little pale before going on, he would tell us to pinch our cheeks,” Chaplin recalled,“But in London, after working two or three Music Halls a night, we would occasionally forget and look a little weary and bored as we stood on the stage, until we caught sight of Mr Jackson in the wings, grinning emphatically and pointing to his face, which had an electrifying effect of making us break into sparkling grins.”

requires to hold an audience. “Audiences like The Eight Lancashire Lads because, as Mr Jackson said, we were so unlike theatrical children. It was his boast that we never wore grease paint and our rosy cheeks were natural. If some of us looked a little pale before going on, he would tell us to pinch our cheeks,” Chaplin recalled,“But in London, after working two or three Music Halls a night, we would occasionally forget and look a little weary and bored as we stood on the stage, until we caught sight of Mr Jackson in the wings, grinning emphatically and pointing to his face, which had an electrifying effect of making us break into sparkling grins.”

Yet Chaplin’s experience touring Britain when Music Hall was at its peak of popularity proved both a great adventure and an unparalleled schooling in the method, technique and discipline that every performer

requires to hold an audience. “Audiences like The Eight Lancashire Lads because, as Mr Jackson said, we were so unlike theatrical children. It was his boast that we never wore grease paint and our rosy cheeks were natural. If some of us looked a little pale before going on, he would tell us to pinch our cheeks,” Chaplin recalled,“But in London, after working two or three Music Halls a night, we would occasionally forget and look a little weary and bored as we stood on the stage, until we caught sight of Mr Jackson in the wings, grinning emphatically and pointing to his face, which had an electrifying effect of making us break into sparkling grins.”

requires to hold an audience. “Audiences like The Eight Lancashire Lads because, as Mr Jackson said, we were so unlike theatrical children. It was his boast that we never wore grease paint and our rosy cheeks were natural. If some of us looked a little pale before going on, he would tell us to pinch our cheeks,” Chaplin recalled,“But in London, after working two or three Music Halls a night, we would occasionally forget and look a little weary and bored as we stood on the stage, until we caught sight of Mr Jackson in the wings, grinning emphatically and pointing to his face, which had an electrifying effect of making us break into sparkling grins.”

above Chaplins return to London

The handbills for the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties date from 1900 and, significantly, one contains the announcement of Edisonograph Animated Pictures as part of the programme, advertising the new medium in which Chaplin was to become pre-eminent and that would eventually eclipse Music Hall itself.

The handbills for the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties date from 1900 and, significantly, one contains the announcement of Edisonograph Animated Pictures as part of the programme, advertising the new medium in which Chaplin was to become pre-eminent and that would eventually eclipse Music Hall itself.

As soon as he had mastered the dance act, Chaplin was impatient to move on to solo comedy. “I was not particularly enamoured with being just a clog dancer in a troupe of eight lads. Like the rest of them I was ambitious to do a single act, not only because it meant more money but because I instinctively felt it would be more gratifying than just dancing,” he wrote later of his precocious ten-year-old self, “I would like to have been a boy comedian – but that would have required nerve, to stand on the stage alone.”

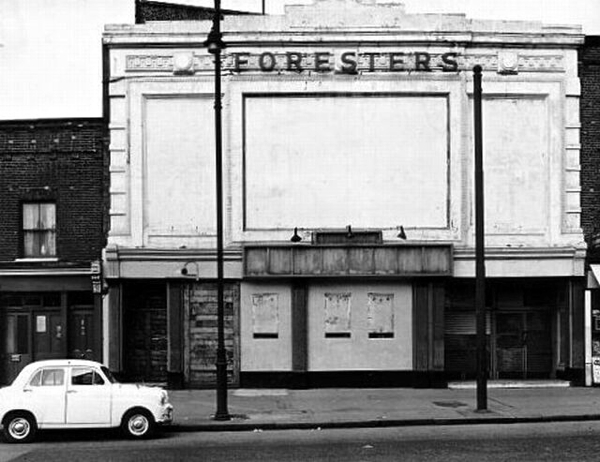

It was in Whitechapel in the autumn of 1907 that the seventeen-year-old Chaplin made his solo comedy debut, at a Music Hall in the Cambridge Heath Rd. “I had obtained a trial week without pay at the Foresters’ Music Hall situated off the Mile End Rd in the centre of the Jewish quarter. My hopes and dreams depended on that trial week,” he declared. Yet the young Chaplin made a spectacular misjudgement. “At the time, Jewish comedians were all the rage in London, so I thought I would hide my youth under whiskers. I invested in musical arrangements for songs and funny dialogue taken from an American joke book, Madison’s Budget.” Chaplin was foolishly unaware that a Jewish satire might not play in the East End in front of a Jewish audience.“Although I was innocent of it, my comedy was most anti-Semitic and my jokes were not only old ones but very poor, like my Jewish accident.”

“I had obtained a trial week without pay at the Foresters’ Music Hall situated off the Mile End Rd in the centre of the Jewish quarter. My hopes and dreams depended on that trial week,” he declared. Yet the young Chaplin made a spectacular misjudgement. “At the time, Jewish comedians were all the rage in London, so I thought I would hide my youth under whiskers. I invested in musical arrangements for songs and funny dialogue taken from an American joke book, Madison’s Budget.” Chaplin was foolishly unaware that a Jewish satire might not play in the East End in front of a Jewish audience.“Although I was innocent of it, my comedy was most anti-Semitic and my jokes were not only old ones but very poor, like my Jewish accident.”

“I had obtained a trial week without pay at the Foresters’ Music Hall situated off the Mile End Rd in the centre of the Jewish quarter. My hopes and dreams depended on that trial week,” he declared. Yet the young Chaplin made a spectacular misjudgement. “At the time, Jewish comedians were all the rage in London, so I thought I would hide my youth under whiskers. I invested in musical arrangements for songs and funny dialogue taken from an American joke book, Madison’s Budget.” Chaplin was foolishly unaware that a Jewish satire might not play in the East End in front of a Jewish audience.“Although I was innocent of it, my comedy was most anti-Semitic and my jokes were not only old ones but very poor, like my Jewish accident.”

“I had obtained a trial week without pay at the Foresters’ Music Hall situated off the Mile End Rd in the centre of the Jewish quarter. My hopes and dreams depended on that trial week,” he declared. Yet the young Chaplin made a spectacular misjudgement. “At the time, Jewish comedians were all the rage in London, so I thought I would hide my youth under whiskers. I invested in musical arrangements for songs and funny dialogue taken from an American joke book, Madison’s Budget.” Chaplin was foolishly unaware that a Jewish satire might not play in the East End in front of a Jewish audience.“Although I was innocent of it, my comedy was most anti-Semitic and my jokes were not only old ones but very poor, like my Jewish accident.”The disastrous consequences of Chaplin’s error in Whitechapel were to haunt him for the rest of his career. “After the first couple of jokes, the audience started throwing coins and orange peel and stamping their feet and booing. At first, I was not conscious of what was going on. Then the horror of it filtered into my mind. When I came off stage, I went straight to my dressing room, took off my make-up, left the theatre and never returned. I did my best to erase the night’s horror from my mind, but it left an indelible mark on my confidence.” he concluded in hindsight, conceding, “The ghastly experience taught me to see myself in a truer light.”

In 1908, Chaplin signed with Fred Karno’s comedy company in which he quickly became a rising star and, touring to America in 1913,This is Tagg's Island, a haven for houseboats and wildlife.

in which he quickly became a rising star and, touring to America in 1913,This is Tagg's Island, a haven for houseboats and wildlife. Fred Wescott was an entertainer and used to busk at the lock near Hampton Court at weekends. He made a pledge that once he had the money, the first thing he would do would be to have houseboat on Taggs Island.His houseboat, the Astoria,

Fred Wescott was an entertainer and used to busk at the lock near Hampton Court at weekends. He made a pledge that once he had the money, the first thing he would do would be to have houseboat on Taggs Island.His houseboat, the Astoria, on the River Thames at Hampton, Middlesex, is now used as a recording studio by Pink Floyd's David Gilmour.

on the River Thames at Hampton, Middlesex, is now used as a recording studio by Pink Floyd's David Gilmour. He changed his name to Fred Karno and made his fame and fortune from Fred Karno's Circus. His list of recruits to his troupe is extensive; Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel, Will Hay, Max Miller, Flanagan and Allen.In 1912 he built a 'sumptuous palace'

He changed his name to Fred Karno and made his fame and fortune from Fred Karno's Circus. His list of recruits to his troupe is extensive; Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel, Will Hay, Max Miller, Flanagan and Allen.In 1912 he built a 'sumptuous palace' that had a resident orchestra and a young musician named Jack Hylton, who 30 years later was to become a theatrical impresario.

that had a resident orchestra and a young musician named Jack Hylton, who 30 years later was to become a theatrical impresario.

During the 2nd World War the island was taken over by AC Cars who converted the hotel to a factory had a bridge built from the Middlesex bank. After the war AC cars made their renowned 3 wheeled invalid carriages on the island and the trains for Southend Pier.

had a bridge built from the Middlesex bank. After the war AC cars made their renowned 3 wheeled invalid carriages on the island and the trains for Southend Pier.

The bridge collapsed in 1965 and the hotel demolished in 1971.

was talent spotted by the Keystone Film Studios and offered a contract at twenty-four years old for $150 a week. “What had happened? It seemed the world had suddenly changed, had taken me into its fond embrace and adopted me.” he wrote in astonishment and relief at his change of fortune in a life that had previously comprised only struggle.

in which he quickly became a rising star and, touring to America in 1913,This is Tagg's Island, a haven for houseboats and wildlife.

in which he quickly became a rising star and, touring to America in 1913,This is Tagg's Island, a haven for houseboats and wildlife. Fred Wescott was an entertainer and used to busk at the lock near Hampton Court at weekends. He made a pledge that once he had the money, the first thing he would do would be to have houseboat on Taggs Island.His houseboat, the Astoria,

Fred Wescott was an entertainer and used to busk at the lock near Hampton Court at weekends. He made a pledge that once he had the money, the first thing he would do would be to have houseboat on Taggs Island.His houseboat, the Astoria, on the River Thames at Hampton, Middlesex, is now used as a recording studio by Pink Floyd's David Gilmour.

on the River Thames at Hampton, Middlesex, is now used as a recording studio by Pink Floyd's David Gilmour. He changed his name to Fred Karno and made his fame and fortune from Fred Karno's Circus. His list of recruits to his troupe is extensive; Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel, Will Hay, Max Miller, Flanagan and Allen.In 1912 he built a 'sumptuous palace'

He changed his name to Fred Karno and made his fame and fortune from Fred Karno's Circus. His list of recruits to his troupe is extensive; Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel, Will Hay, Max Miller, Flanagan and Allen.In 1912 he built a 'sumptuous palace' that had a resident orchestra and a young musician named Jack Hylton, who 30 years later was to become a theatrical impresario.

that had a resident orchestra and a young musician named Jack Hylton, who 30 years later was to become a theatrical impresario.

During the 2nd World War the island was taken over by AC Cars who converted the hotel to a factory

had a bridge built from the Middlesex bank. After the war AC cars made their renowned 3 wheeled invalid carriages on the island and the trains for Southend Pier.

had a bridge built from the Middlesex bank. After the war AC cars made their renowned 3 wheeled invalid carriages on the island and the trains for Southend Pier.The bridge collapsed in 1965 and the hotel demolished in 1971.

was talent spotted by the Keystone Film Studios and offered a contract at twenty-four years old for $150 a week. “What had happened? It seemed the world had suddenly changed, had taken me into its fond embrace and adopted me.” he wrote in astonishment and relief at his change of fortune in a life that had previously comprised only struggle.

Now I shall always think of the ten-year-old Chaplin when I walk down Commercial St, on his way to the Cambridge Theatre of Varieties, pinching his sallow cheeks to make a show of good cheer and with his whole life in motion pictures awaiting him.

At the northern end of Commercial St is the site of The Theatre, the first purpose-built theatre,  where William Shakespeare performed and his early plays were staged. At the southern end of Commercial St is the site of the Goodman’s Fields Theatre

where William Shakespeare performed and his early plays were staged. At the southern end of Commercial St is the site of the Goodman’s Fields Theatre where David Garrick made his debut in Richard III and initiated the Shakespeare revival. And in middle was the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties where Charlie Chaplin performed.

where David Garrick made his debut in Richard III and initiated the Shakespeare revival. And in middle was the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties where Charlie Chaplin performed. Most that pass down it may be unaware, yet the line of

Most that pass down it may be unaware, yet the line of  Commercial St traces a major trajectory through our culture.

Commercial St traces a major trajectory through our culture.

The Theatre built in 1576 in the London suburb of Norton Folgate by James Burbage and his head carpenter Peter Street (who later would also build theaters for Burbage’s rival, Philip Henslowe) had a unique shape as can clearly be seen on several birdseye maps of the period. These theaters are not only round, they are at least three or four stories tall, and topped as well by roofed additions of some sort that seem to add another story.

several birdseye maps of the period. These theaters are not only round, they are at least three or four stories tall, and topped as well by roofed additions of some sort that seem to add another story. On these maps they stick out like sore thumbs. Where did this unusual design originate?

On these maps they stick out like sore thumbs. Where did this unusual design originate?

where William Shakespeare performed and his early plays were staged. At the southern end of Commercial St is the site of the Goodman’s Fields Theatre

where William Shakespeare performed and his early plays were staged. At the southern end of Commercial St is the site of the Goodman’s Fields Theatre where David Garrick made his debut in Richard III and initiated the Shakespeare revival. And in middle was the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties where Charlie Chaplin performed.

where David Garrick made his debut in Richard III and initiated the Shakespeare revival. And in middle was the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties where Charlie Chaplin performed. Most that pass down it may be unaware, yet the line of

Most that pass down it may be unaware, yet the line of  Commercial St traces a major trajectory through our culture.

Commercial St traces a major trajectory through our culture.The Theatre built in 1576 in the London suburb of Norton Folgate by James Burbage and his head carpenter Peter Street (who later would also build theaters for Burbage’s rival, Philip Henslowe) had a unique shape as can clearly be seen on

several birdseye maps of the period. These theaters are not only round, they are at least three or four stories tall, and topped as well by roofed additions of some sort that seem to add another story.

several birdseye maps of the period. These theaters are not only round, they are at least three or four stories tall, and topped as well by roofed additions of some sort that seem to add another story. On these maps they stick out like sore thumbs. Where did this unusual design originate?

On these maps they stick out like sore thumbs. Where did this unusual design originate?Charlie Chaplin performed with The Eight Yorkshire Lads at the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in Commercial St on Tuesday 24th October 1899.

The extension of the Godfrey & Wills cigarette factory replaced the demolished Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties in 1936.

The entrance of the Godfrey & Wills building echoes the entrance of the Royal Cambridge Theatre of Varieties.

Foresters Music Hall, 95 Cambridge Heath Rd – where Charlie Chaplin gave his disastrous first solo comedy performance in 1907 – demolished in 1965.

Read the following passage from Jack London’s excellent 1902 piece of ‘slumming’ journalism, ‘The People of the Abyss’:

…I rented no rooms, but returned to my own Johnny Upright’s street. What with my wife, and babies, and lodgers, and the various cubby-holes into which I had fitted them, my mind’s eye had become narrow-angled, and I could not quite take in all of my own room at once.

The immensity of it was awe-inspiring. Could this be the room I had rented for six shillings a week? Impossible! But my landlady, knocking at the door to learn if I were comfortable, dispelled my doubts.

The immensity of it was awe-inspiring. Could this be the room I had rented for six shillings a week? Impossible! But my landlady, knocking at the door to learn if I were comfortable, dispelled my doubts.

“Oh yes, sir,” she said, in reply to a question. “This street is the very last. All the other streets were like this eight or ten years ago, and all the people were very respectable. But the others have driven our kind out. Those in this street are the only ones left. It’s shocking, sir!” And then she explained the process of saturation, by which the rental value of a neighbourhood went up, while its tone went down.

“You see, sir, our kind [English upper-working class – Ed] are not used to crowding in the way the others do. We need more room. The others, the foreigners and lower-class people, can get five and six families into this house, where we only get one. So they can pay more rent for the house than we can afford. It is shocking, sir; and just to think, only a few years ago all this neighbourhood was just as nice as it could be.”

I looked at her. Here was a woman, of the finest grade of the English working-class, with numerous evidences of refinement, being slowly engulfed by that noisome and rotten tide of humanity which the powers that be are pouring eastward out ofLondonTown. Bank, factory, hotel, and office building must go up, and the city poor folk are a nomadic breed; so they migrate eastward, wave upon wave, saturating and degrading neighbourhood by neighbourhood, driving the better class of workers before them to pioneer, on the rim of the city, or dragging them down, if not in the first generation, surely in the second and third. It is only a question of months when Johnny Upright’s street must go. He realises it himself.

“In a couple of years,” he says, “my lease expires. My landlord is one of our kind. He has not put up the rent on any of his houses here, and this has enabled us to stay. But any day he may sell, or any day he may die, which is the same thing so far as we are concerned. The house is bought by a money breeder, who builds a sweat shop on the patch of ground at the rear where my grapevine is, adds to the house, and rents it a room to a family. There you are, and Johnny Upright’s gone!” And truly I saw Johnny Upright, and his good wife and fair daughters, and frowzy slavey, like so many ghosts flitting eastward through the gloom, the monster city roaring at their heels. But Johnny Upright is not alone in his flitting. Far, far out, on the fringe of the city, live the small business men, little managers, and successful clerks. They dwell in cottages and semi-detached villas, with bits of flower garden, and elbow room, and breathing space. They inflate themselves with pride, and throw out their chests when they contemplate the Abyss from which they have escaped, and they thank God that they are not as other men. And lo! down upon them comes Johnny Upright and the monster city at his heels. Tenements spring up like magic, gardens are built upon, villas are divided and subdivided into many dwellings, and the black night ofLondonsettles down in a greasy pall.

American writer Jack London was twenty-six when he wrote ‘The People of the Abyss’ in which he spends three weeks living as a pauper in the East End of London, a vast “killing machine” of chronic starvation, vermin infestation and overcrowding, in order to present the true face of poverty in the worlds richest and most powerful city.

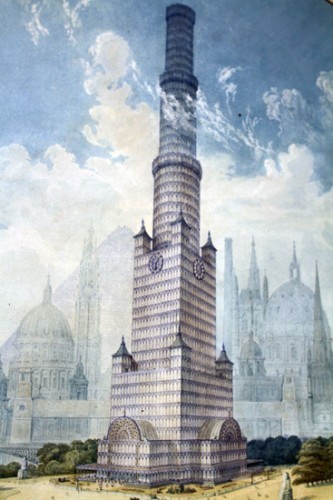

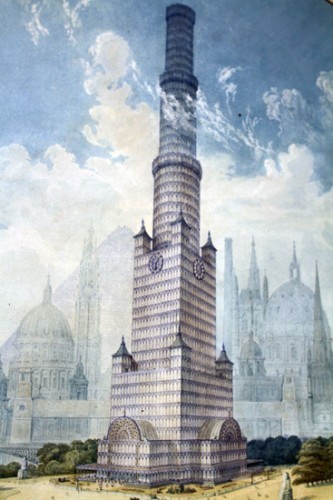

Those days, thankfully, are well and truly over. if history had have been a little different, London would have had a building just a little smaller than The Shard for more than a century.

After the death of Prince Albert in 1861, designs were submitted for a fitting memorial. One architect had the grand idea of breaking down the building that is most associated with the Prince Consort - Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace - and rebuilding it as a 304 metre tall glass tower.

Had this tower of glass and steel been given the go-ahead, it would have been the worlds first  skyscraper, but the memorial chosen in its place was the rather wonderful and grand Albert memorial which sits - as the tower would have done - opposite the Albert Hall.

skyscraper, but the memorial chosen in its place was the rather wonderful and grand Albert memorial which sits - as the tower would have done - opposite the Albert Hall. Over the last fifteen years, the subtle work that Jim Howett has done on numerous shopfronts in Spitalfields has become

Over the last fifteen years, the subtle work that Jim Howett has done on numerous shopfronts in Spitalfields has become  such an integral part of the identity of the neighbourhood, that most people have no idea these edifices were ever any different from how they are today. This is exactly how Jim would wish it of course – it was his intent. He was always pursuing an art that would conceal itself. Yet there is a story behind each one, and it was by no means inevitable that any of these buildings would survive to become the local landmarks we all recognise.

such an integral part of the identity of the neighbourhood, that most people have no idea these edifices were ever any different from how they are today. This is exactly how Jim would wish it of course – it was his intent. He was always pursuing an art that would conceal itself. Yet there is a story behind each one, and it was by no means inevitable that any of these buildings would survive to become the local landmarks we all recognise.

By 'ghosts'

impressions left by previous lives –

on landscape and imagination of the living.

The dead are on Hackney Marshes.

The signs of the dead are everywhere.

Rubble from houses

beneath topsoil.

The filter beds , a memory of cholera, death and technological utopia .

drifting through a dirty dream of reservoirs,

demolished factories,

sewerage systems

power plants

, and rusting barges.

Hear the shouts of long gone.

help reanimate their spirits.

please help them

Sometimes

a sweet dread sense of people

who lived and worked around the canal,

played here,

and drowned here.

Recently I met

a ghostly ghost

imagine me coming back to life

and heaving himself from water

evil dead who shout you fucking cunt,

sorrowful souls who search for living lovers

who reunite with their fellow victims on Halloween and dance in the Victorian filter beds

skyscraper, but the memorial chosen in its place was the rather wonderful and grand Albert memorial which sits - as the tower would have done - opposite the Albert Hall.

skyscraper, but the memorial chosen in its place was the rather wonderful and grand Albert memorial which sits - as the tower would have done - opposite the Albert Hall. Over the last fifteen years, the subtle work that Jim Howett has done on numerous shopfronts in Spitalfields has become

Over the last fifteen years, the subtle work that Jim Howett has done on numerous shopfronts in Spitalfields has become  such an integral part of the identity of the neighbourhood, that most people have no idea these edifices were ever any different from how they are today. This is exactly how Jim would wish it of course – it was his intent. He was always pursuing an art that would conceal itself. Yet there is a story behind each one, and it was by no means inevitable that any of these buildings would survive to become the local landmarks we all recognise.

such an integral part of the identity of the neighbourhood, that most people have no idea these edifices were ever any different from how they are today. This is exactly how Jim would wish it of course – it was his intent. He was always pursuing an art that would conceal itself. Yet there is a story behind each one, and it was by no means inevitable that any of these buildings would survive to become the local landmarks we all recognise.The nature of the location of Spitalfields at the boundary of the volatile City of London renders the neighbourhood as one that is always in a state of change. It was in the late eighties, when the departure of fruit & vegetable market was imminent and developers were hungrily eyeing up the opportunities, that the Spitalfields Trust set about purchasing buildings in Brushfield St. Ironically this undervalued terrace facing the market was itself created by a brutal stroke in 1780,

Ironically this undervalued terrace facing the market was itself created by a brutal stroke in 1780,  when a new road named Union St was driven through linking Christ Church with Finsbury Sq (the other half of this road still exists as Sun St on the other side of Liverpool St Station).

when a new road named Union St was driven through linking Christ Church with Finsbury Sq (the other half of this road still exists as Sun St on the other side of Liverpool St Station).  starbucks in brushfield street, u never use it ok

starbucks in brushfield street, u never use it ok

In the process, structures were sliced in half, leaving buildings only one room thick, and refaced with windows in the odd positions that accommodated to the circumstances, defining the unusual rhythm of this terrace today.

Ironically this undervalued terrace facing the market was itself created by a brutal stroke in 1780,

Ironically this undervalued terrace facing the market was itself created by a brutal stroke in 1780,  when a new road named Union St was driven through linking Christ Church with Finsbury Sq (the other half of this road still exists as Sun St on the other side of Liverpool St Station).

when a new road named Union St was driven through linking Christ Church with Finsbury Sq (the other half of this road still exists as Sun St on the other side of Liverpool St Station).  starbucks in brushfield street, u never use it ok

starbucks in brushfield street, u never use it okIn the process, structures were sliced in half, leaving buildings only one room thick, and refaced with windows in the odd positions that accommodated to the circumstances, defining the unusual rhythm of this terrace today.

When designer Marianna Kennedy and husband Charles Gledhill, bookbinder, bought 42 Brushfield St from the Trust in 1996, the ground floor had been stripped out for use as a vegetable store and it fell to  Jim to design a shopfront that would be in keeping, so that the space could be used as a workshop and showroom. Without money to spend, they were lucky to attract the attention of a film crew that needed a

Jim to design a shopfront that would be in keeping, so that the space could be used as a workshop and showroom. Without money to spend, they were lucky to attract the attention of a film crew that needed a shopfront location for an episode of Maigret. The location fee covered the cost of construction and, once his design was approved by the conservation officer,

shopfront location for an episode of Maigret. The location fee covered the cost of construction and, once his design was approved by the conservation officer,  worked through the night to complete the work. And when the crew arrived on the first morning of filming, the paint was still wet.

worked through the night to complete the work. And when the crew arrived on the first morning of filming, the paint was still wet.

Jim to design a shopfront that would be in keeping, so that the space could be used as a workshop and showroom. Without money to spend, they were lucky to attract the attention of a film crew that needed a

Jim to design a shopfront that would be in keeping, so that the space could be used as a workshop and showroom. Without money to spend, they were lucky to attract the attention of a film crew that needed a shopfront location for an episode of Maigret. The location fee covered the cost of construction and, once his design was approved by the conservation officer,

shopfront location for an episode of Maigret. The location fee covered the cost of construction and, once his design was approved by the conservation officer,  worked through the night to complete the work. And when the crew arrived on the first morning of filming, the paint was still wet.

worked through the night to complete the work. And when the crew arrived on the first morning of filming, the paint was still wet.

Jim’s design was based upon a thorough knowledge of East End shopfronts both existing and as recorded in old photographs, and the success of this key piece of work led to it becoming the model for the other  traditional shopfronts at the Bishopsgate end of Brushfield St, but a comparison reveals that these are

traditional shopfronts at the Bishopsgate end of Brushfield St, but a comparison reveals that these are  mechanical reproductions. They lack the idiosyncrasy and craft details of Jim’s work. At number forty-two, he used cedar wood that would provide longevity and a textured grain, and he planed the sashes by

mechanical reproductions. They lack the idiosyncrasy and craft details of Jim’s work. At number forty-two, he used cedar wood that would provide longevity and a textured grain, and he planed the sashes by  hand. It is this attention to intriguing authentic detail - he built-in rising sashes that allow for an open shop window

hand. It is this attention to intriguing authentic detail - he built-in rising sashes that allow for an open shop window - combined with an understanding of the proportion and the dignity of utilitarian design that makes Jim’s understated work so pleasing.

- combined with an understanding of the proportion and the dignity of utilitarian design that makes Jim’s understated work so pleasing.

traditional shopfronts at the Bishopsgate end of Brushfield St, but a comparison reveals that these are

traditional shopfronts at the Bishopsgate end of Brushfield St, but a comparison reveals that these are  mechanical reproductions. They lack the idiosyncrasy and craft details of Jim’s work. At number forty-two, he used cedar wood that would provide longevity and a textured grain, and he planed the sashes by

mechanical reproductions. They lack the idiosyncrasy and craft details of Jim’s work. At number forty-two, he used cedar wood that would provide longevity and a textured grain, and he planed the sashes by  hand. It is this attention to intriguing authentic detail - he built-in rising sashes that allow for an open shop window

hand. It is this attention to intriguing authentic detail - he built-in rising sashes that allow for an open shop window - combined with an understanding of the proportion and the dignity of utilitarian design that makes Jim’s understated work so pleasing.

- combined with an understanding of the proportion and the dignity of utilitarian design that makes Jim’s understated work so pleasing.

At the same time, Jim also found Mr Verde’s daybooks from the nineteen thirties recording his visits to  farmers in France under the name Jean Verde, farmers in Spain under the name Juan Verde and farmers in Italy under the name Julio Verde.

farmers in France under the name Jean Verde, farmers in Spain under the name Juan Verde and farmers in Italy under the name Julio Verde.  These daybooks revealed that Mr Verde was scrupulously fair with his suppliers, informing them that never less than nine-tenths of their produce had arrived in good order with no more than one tenth spoilt. Recalling Mr Verde and the other vegetable traders of Brushfield St,

These daybooks revealed that Mr Verde was scrupulously fair with his suppliers, informing them that never less than nine-tenths of their produce had arrived in good order with no more than one tenth spoilt. Recalling Mr Verde and the other vegetable traders of Brushfield St,  told me, “They traded in mushrooms, watercress and potatoes, and were in their seventies when I knew them, many fought together during the Italian Campaign, and their families had intermarried. And they ran an unlicensed horse betting racket that earned them more than the vegetable trade!”

told me, “They traded in mushrooms, watercress and potatoes, and were in their seventies when I knew them, many fought together during the Italian Campaign, and their families had intermarried. And they ran an unlicensed horse betting racket that earned them more than the vegetable trade!”

farmers in France under the name Jean Verde, farmers in Spain under the name Juan Verde and farmers in Italy under the name Julio Verde.

farmers in France under the name Jean Verde, farmers in Spain under the name Juan Verde and farmers in Italy under the name Julio Verde.  These daybooks revealed that Mr Verde was scrupulously fair with his suppliers, informing them that never less than nine-tenths of their produce had arrived in good order with no more than one tenth spoilt. Recalling Mr Verde and the other vegetable traders of Brushfield St,

These daybooks revealed that Mr Verde was scrupulously fair with his suppliers, informing them that never less than nine-tenths of their produce had arrived in good order with no more than one tenth spoilt. Recalling Mr Verde and the other vegetable traders of Brushfield St,  told me, “They traded in mushrooms, watercress and potatoes, and were in their seventies when I knew them, many fought together during the Italian Campaign, and their families had intermarried. And they ran an unlicensed horse betting racket that earned them more than the vegetable trade!”

told me, “They traded in mushrooms, watercress and potatoes, and were in their seventies when I knew them, many fought together during the Italian Campaign, and their families had intermarried. And they ran an unlicensed horse betting racket that earned them more than the vegetable trade!”

While Jim was doing his work at one end of Brushfield St, Peter Sinden’s renovation of the Market Coffee House (the oldest surviving building in Spitalfields, dating from the seventeenth century), bookended the  terrace, securing the personality of this block of buildings with so much to tell about Spitalfields history.“It just shows that if you cherish a neighbourhood, you can make it something better than it is.”disclosed Jim, with proprietory delight. In finding such ingenious and modest ways to design shopfronts that are in tune with each of these frontages, Jim Howett has contributed to preserving buildings that are distinctive in Spitalfields. They tell the history of working people here over the last two centuries, allowing their presence to remain visible on the street to remind us every day of those who were here before us.

terrace, securing the personality of this block of buildings with so much to tell about Spitalfields history.“It just shows that if you cherish a neighbourhood, you can make it something better than it is.”disclosed Jim, with proprietory delight. In finding such ingenious and modest ways to design shopfronts that are in tune with each of these frontages, Jim Howett has contributed to preserving buildings that are distinctive in Spitalfields. They tell the history of working people here over the last two centuries, allowing their presence to remain visible on the street to remind us every day of those who were here before us.

terrace, securing the personality of this block of buildings with so much to tell about Spitalfields history.“It just shows that if you cherish a neighbourhood, you can make it something better than it is.”disclosed Jim, with proprietory delight. In finding such ingenious and modest ways to design shopfronts that are in tune with each of these frontages, Jim Howett has contributed to preserving buildings that are distinctive in Spitalfields. They tell the history of working people here over the last two centuries, allowing their presence to remain visible on the street to remind us every day of those who were here before us.

terrace, securing the personality of this block of buildings with so much to tell about Spitalfields history.“It just shows that if you cherish a neighbourhood, you can make it something better than it is.”disclosed Jim, with proprietory delight. In finding such ingenious and modest ways to design shopfronts that are in tune with each of these frontages, Jim Howett has contributed to preserving buildings that are distinctive in Spitalfields. They tell the history of working people here over the last two centuries, allowing their presence to remain visible on the street to remind us every day of those who were here before us.

dead people

impressions left by previous lives –

on landscape and imagination of the living.

The dead are on Hackney Marshes.

The signs of the dead are everywhere.

Rubble from houses

beneath topsoil.

The filter beds , a memory of cholera, death and technological utopia .

drifting through a dirty dream of reservoirs,

demolished factories,

sewerage systems

power plants

, and rusting barges.

Hear the shouts of long gone.

help reanimate their spirits.

please help them

Sometimes

a sweet dread sense of people

who lived and worked around the canal,

played here,

and drowned here.

Recently I met

a ghostly ghost

imagine me coming back to life

and heaving himself from water

evil dead who shout you fucking cunt,

sorrowful souls who search for living lovers

who reunite with their fellow victims on Halloween and dance in the Victorian filter beds

No comments:

Post a Comment