I Said, " I

I Said, " I am awfully sorry but I am afraid that I have had

too many champagne cocktails and may fall asleep

or scream, will you meet me here to-morrow? "

They were charming and said that they would and

I was conveyed home to bed. I saw him several

times, and the day he left Paris I had luncheon with

him and he gave me a hundred francs and asked me

if I would buy myself some flowers. I did, but a

very small bunch, and lived in comfort for the rest

of the week. I have never seen him since but hope,

perhaps, that he will see this book and know that I

have not completely vanished.

I don't much like writing about funerals, but I

shall have to because Erik Satie died and I thought

that I ought to go to his. He lived at Arcueuil with

his umbrellas and was to be buried there in the

village church. I took a train on the morning of

the funeral at the Gare d 3 Orleans by myself. On

the platform waiting for the train was the painter

Ortiz de ZarateNude above.

I found that he was going to the

funeral too and so we got into the same carriage;

I was glad to have someone to go with. When

we got to Arcueuil we asked the way to the church,

which was about ten minutes' walk. The ceremony

had already begun. The church was filled, there

were politicians and all the Boeuf, Brancusi, Cocteau,

Moise, Valentine and Jean Hugo, Yvonne George,

Wassilieff, all Les Six, and the Ecole d 5 Arcueuil,

Erik Satie's own school of musicians, of which

Sauguet is the only one whose name I can re

member. This was the second funeral I had

gone to, and, although it was very sad, as I missed

my afternoon seances with Satie at the Dome,

he was an old man and had lived his life and

had had a lot of fun, it was not so tragic as that of

Radiguet, who was so young. After the service

we started for the cemetery, which was about a mile

away. The men followed on foot first, walking four

abreast. There must have been at least fifteen

hundred people present. Afterwards walked the

women. Yvonne George, Valentine Hugo, Wassilieff

and myself headed the procession. There were

many very respectable French bourgeoises, all dressed

in deep mourning. These I found out afterwards

were the wives of all the keepers of cafes in Arcueuil

where Satie had had aperitifs. At the cemetery we

stood by the graveside and saw the coffin laid in the

grave and shook the relatives by the hand and went

back to Paris. I had a most beautiful letter from

Satie that he wrote me on one occasion when I asked

him to come to a ball that I was arranging with some

Americans. I said that I would " dance like the

devil " for his benefit. Alas! he could not come as

it was a very late affair. He answered my letter

and said that he was sure that it was impossible

for me to " Dance like the devil " as I was

" beaucoup trop gentitte" Unfortunately, I have

lost it.

I was at this time very broke and very gloomy.

F. and R. asked me to stay with them in their

castle and I very much wanted to go. I was in

pawn at my hotel and could not move, so had to

wait patiently until something turned up. A very

nice Englishman, Dreydell, turned up whom I had

met before. He suggested that I should have an ex

hibition in London that he would arrange for me to

have at the Claridge Gallery, in Brook Street. I had

a good many oil-paintings that I had never exhibited

before, and quite enough for a good exhibition. He

bought a still life of mine and paid me twelve hun

dred francs. I was delighted and wired immediately

to F. that I was arriving at any moment. I paid

the hotel bill and felt very light-hearted and free

again. The next day I caught a violent cold and

that evening had to go to bed with a high tempera

ture. I was living alone at that time in the Rue

Campagne Premiere

. In the same hotel lived three

. In the same hotel lived three people who were charming, but generally spent

every night dancing and drinking in Montmartre,

arriving home at seven or eight in the morning.

They generally bounced into my room to inform

me of the scandals of the night, which they managed

to hiccough out. At seven a.m. they arrived in

evening-dress. I said I was very ill. They were

very upset and brought me -a bottle of brandy and

tottered off to their beds. I looked at it and decided

that I should, on the whole, prefer a lingering death

rather than a sudden one and went to sleep. I

managed to sleep all day and at six-thirty a doctor

friend of mine happened to call and see me. He

gave me one look and said, " Have you any money? "

I gave him fifty francs and he went out and bought

various pills, potions, and appliances, and within

ten minutes my temperature was considerably less.

By this time my neighbours had come to, and

were appalled to think that they had not fetched a

doctor in the morning. I suggested that they should

have some brandy; and console themselves as it

wasn't really very serious. The same evening the

doctor came to see how I was, and he and a friend

of mine finished the brandy and staggered home

arm-in-arm.

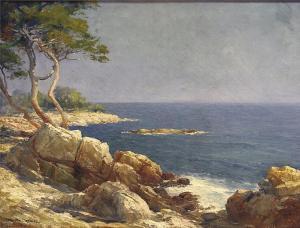

I BEGAN to pack my things and think about the

South of France. The Pole saw me off at the station.

I armed myself with a bottle of red wine. The train

was full and the only seat I could find (I travelled,

of course, third class), was in a carriage filled with

French sailors. In the corner was a very small

ginger-haired French soldier. I sat down in a

corner. The sailors opened their bottles and offered

me some wine.

We then all drank together. They

We then all drank together. They were all Bretons and we talked about Brittany.

Next to me was a very good-looking, golden-haired

sailor, who got very drunk, and, after making an

unsuccessful attempt to kiss me, fell asleep with his

head on my lap. I felt slightly embarrassed but

thought it better to remain still, hoping that even

tually he would become conscious and that I could

change my position. The other sailors and the little

soldier were already asleep and I lay my head

against the window and slept too. About five in the

morning I woke up and from the opposite corner of

the carriage the soldier spoke to me in the most

perfect " Oxford English." I thought, " Good God!

He probably knows all kinds of people that I do and

here am I with a sailor asleep with his head on my

lap I asked him why he spoke English and he told

me that he had been brought up in England and

that his Father was a Frenchman, and he, being a

French subject, had to do his Service Militaire. He

had been in Egypt before in some kind of political job

and had to leave it to join the Army. He said that

the food was very bad but his family gave him

money so that he could feed himself. He was per

fectly charming and at Toulon the sailors got off,

feeling rather ill and bad-tempered, and the soldier

and myself continued, standing in the corridor, talk

ing and looking at the landscape. When I arrived

at Cannes, my friends were waiting for me on

the platform. The soldier got out and I intro

duced him to them. We asked him to have a drink

with us but he had to wait for another train to

take him to Nice and had not got time. F. was

not at all surprised to see me with a French soldier,

as he is one of those sensible people who are not

at all surprised at anything.

I was very dirty indeed and I had some food at

the Cafe de Paris, which is, or was I think it no

longer exists opposite the Casino. We then

motored to the house, which was on the road to

Grasse, but about two miles from the main road.

It was a most beautiful old house, built about 1802,

on a hill surrounded by mimosa trees, which were in

full bloom. The yellow flowers in the sunlight were

so bright and dazzling that one had to blink one's

eyes for a few seconds before one could see. In the

front of the house was a hilly lawn with some big

trees. The whole lawn was covered in the biggest

and sweetest smelling violets that I have ever seen.

There were several farmhouses on the estate, quite

near the house, surrounded by olive trees and

a small, strangely shaped, and very fat donkey with

an enormous head. I did not get on very well with

It as, whenever I sat outside and attempted to draw,

it would lay Its head on my lap or try and swallow

the Indian ink. There was also a tame sheep which

was very fond of walking into the drawing-room

and tucking itself up comfortably on the sofa. This

had to be discouraged in wet weather as it did not

wipe its feet. I had the most beautiful bedroom

with a large and very comfortable bed. I also had

a bathroom to myself and a kind lady came and

asked me if I wanted any mending done. I felt that

at last I had arrived in Paradise. The house had a

wide winding staircase. The rest of the house had

been painted with coloured patterns which, unfor

tunately, had disappeared, principally owing to the

damp. At the back of the house was a lake filled with

fish and a small and very beautiful island with mi

mosa trees on it. On the far side was a bed of irises.

We were on the top of a steep hill and the ground

sloped down. The other side of the pond, behind

the irises, which could be seen from the house, we

could see in the distance the sea, and at night the

Esterelle. At one side of the house was a valley and,

in the distance, more and bigger mountains. These

had snow on the top of them, and in the early mom-

ing were the most wonderful colour. Near the house

was a pear-tree in bloom. I think I have already

mentioned that near Paris, there were orchards

filled with pear blossoms which I never had the

courage to paint; but every day I looked at this

tree and determined to try. For the background

there were trees on the hill as it sloped towards the

valley, and over their tops were the distant snow-

capped mountains and the blue sky. To my sur

prise I found that blossom was very much easier to

paint than many other subjects and it turned out

to be, I think, one of my best pictures. Even F.

liked it. It is now in the collection of Roy Randall.

We had breakfast in our pyjamas and dressing-

gowns and then walked about the estate accom

panied by a very fat white mongrel, which waddled

and wheezed, and was called Zezette. Poor

Zezette very much shocked the smart French people

who visited us, as they expected that F., with

such a fine chateau, would have, if not Borzois in

attendance, at least Alsatians or something rather

grand.

I worked in the morning and afterwards we sat

in the sun and drank cocktails till lunch. The

cook was a fat Frenchwoman and I have never eaten

so much or such good food. I felt myself growing

fatter every day, which indeed I was. I am afraid

that I slept generally during the afternoon. Every

evening I insisted on putting on one of my nine

evening-dresses, and had great pleasure in sweeping

up and down the wide staircase and imagining that

I was rich. F. would put his head out of his sitting-

room now and then and hand out instructions on

the subject of deportment. F. and R. never worried

about changing and generally had dinner in their

ordinary clothes and espadrilles. After dinner we

sat in a little room which has now, I believe, a

mosaic floor designed by Picasso. F. would discourse

on life and the beastliness of the human race and

R. and I would listen. Once I inadvertently men-

tioned my admiration for Marie BashkirtsefF as a

person, and was so shaken by the torrent of abuse

that I received from F., that I had recourse to the

brandy-bottle for a few minutes to recover. I think,

and still do, that F. is the most intelligent person that

I have ever met. He seemed to have read everything

that had ever existed. I had the sense to make notes

of many of his views and of all the books that he men

tioned, all of which I shall certainly not live long

enough to read. We read Fantomas, that series of

French cc bloods " in forty-two volumes, all of which

Max Jacob and Cocteau have read. F. drew most

beautifully and did two paintings of me which

he never actually finished because he decided that

he could not attain to the perfection of his original

conception. He might have been a great artist if

he had not been so intelligent and so critical. R.

was a portrait painter of considerable talent and had

had a good deal of success in Paris and, in fact, had

made quite a lot of money, but being so far from

anywhere and managing the estate, he did not paint

very much.

We motored into Cannes one morning to do some

shopping and have some cocktails at a large hotel

on the Promenade. It was filled with English and

Americans; one could easily pick out the English as

they all sat with small bottles of champagne in front

of them instead of cocktails, a habit of which I

thoroughly approved. F. heard from Francis

Poulenc to say that he was coming to Cannes to stay

with his Tante Lena, who was eighty, and F.

wrote and asked him to stay with us for a few weeks.

I knew him quite well a

nd was delighted, as he was

nd was delighted, as he was most amusing and intelligent, as all Les Six were.

We went to Cannes to fetch him from his Aunt's

house. He had a room next to mine. It was a small

room papered with the most wonderful eighteenth-

century wall-paper, with a landscape continuing all

round the walls. It looked like a Henri Rousseau

and had large snakes and huge trees and alligators

coining out of the water. F. was very proud of

this room as it had a wicker bed. I believe that it

was actually very uncomfortable, but F. showed it

to everyone with great pride.

Poulenc composed all the morning; I painted the

pear-tree and F. came and gave first Poulenc,

and then myself, advice on our respective arts. It

was delightful to paint in the sun and hear pleasant

music at the same time, and I was perfectly happy.

I taught Poulenc some of my songs, which he in

vented accompaniments to, and I sang them some

times to the French people who visited us. Poulenc

was terrified of birds and one morning, at about five

o'clock, I heard a knock on my door, and there was

Poulenc, who said, " Venez ici y faipeur" and under

the water-pipes of his room was a fluttering sparrow,

which he could not bear to pick up. I put my hand

underneath and took it out and threw it out of the

window. By this time the cook, who slept under

neath, had heard voices and poked her head out of

the window. She looked up in astonishment and

saw our frightened faces and the fluttering spar

row.

We went to Grasse one day and found Nicole

Groult, the dressmaker, and Madame Jasmy van

Dongen. They arranged a luncheon-party at the

hotel, which we went to. There were only French

people present and we had a wonderful time.

Poulenc and I found some gambling machines in the

bar of the hotel and proceeded to lose francs until

we were dragged away by F. and R. Grasse is

a dreadful place and smells of bad scent. I asked

Poulenc to sit for me, which he did, for an hour

every day. I thought that he should wear a button

hole, and we all walked round the estate to choose

a flower of a suitable colour. The ground was

covered with wild anemones of all colours and I

chose a pinkish purple one, which looked well on a

grey-green suit. The portrait was a very good like

ness but a drawing I did I liked better. The drawing

was reproduced in the Burlington Magazine some years

ago, with one of Auric also.

Madame Porel, the daughter-in-law of Rejane,

came to lunch one day. She was very chic and very

nice. Harry Melvill was staying in Cannes at the

time and came over frequently to see us. One day

he came to lunch and said that he had just been to

see Monsieur Patou, the dressmaker, and that Mon

sieur Patou had been talking about the Queen. We

asked what he had said, and Harry said, " He said

that the Queen was forty-seven, and I said, c But

Monsieur Patou, the Queen must be more than

forty-seven/ and Monsieur Patou said, c I am not

talking about her age, I am talking about her

bust. 3 " When Harry talked about the happenings

of the evening before, or the present time, he was

very funny, but he had a large stock of old stories

that got a little wearying after a time.

My birthday is on the same day as F.'s, but

he is older than I am. It is Valentine's day, the

fourteenth of February, and he arranged a birthday

party. We asked Harry Melvill, a French Countess

and her husband, and a tall and distinguished

Englishwoman who was staying at Cannes, and we

hired a waiter from the hotel at Grasse. The waiter

proved to be quite mad and very inefficient.

Speeches were made and we drank a magnum of

champagne and walked and talked in the garden

afterwards. One day we went to Nice to see

Monsieur Gentilhomme, the tailor.

20s french oxfords

20s french oxfordsWe went to

Vogade's, where we found Honegger and Stravin

sky. Stravinsky had to be fitted at the tailor's and

we all went round there, where he was to meet his

wife and children. He had with him two little

pictures that he had just had framed. They were

sewn in needlework and designed by his two small

daughters. They were very beautifully drawn and

he was very proud of them. His eldest son came to

meet him with his Mother. F., R., and I went back

to Vogade's and talked to Honegger. We asked

Stravinsky and his wife to lunch with us at Faletto's,

a restaurant on the road from Nice to Monte

Carlo, in a week's time. A few days later a motor

car arrived at our house and Stravinsky and his

son appeared. This was before dinner. We always

had a tin of caviare presse which I had to spread

thinly on toast. Stravinsky seized a spoon and

dug spoonfuls out of the tin and then played on

our harmonium the fair tune out of Petrouchka.

They stayed to dinner, Stravinsky sat beside me and

presented me with a glass cigarette holder.

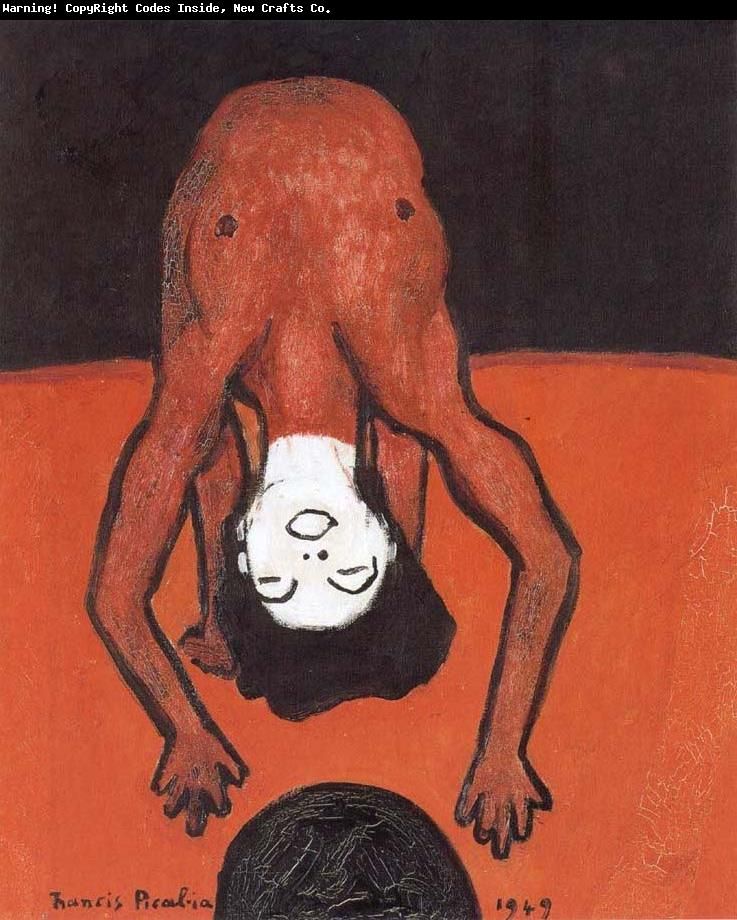

Picabia, the Dadaist, lived not far away from us

and we went with Harry Melvill to his house. The

house was so full of things, ornaments, pictures,

furniture, that it was almost impossible to move

without upsetting something. He came to lunch

with us and brought with him Marthe Chenal, the

famous opera-singer. She sang the c c Marseillaise ' * on

the steps of the Madeleine during the War, and had

a wonderful voice. She was the most magnificent-

looking creature, very tall, with a wonderful figure

and a beautiful and very animated face, with curious

purplish-red Medusa-like curls all over her head.

Poulenc tried to induce her to sing, but she would

not, but asked us all to a box at the Casino at

Cannes, where she was playing cc Carmen." Poulenc

sang his latest songs which were composed for the

words of some old and rather naughty French

poems of the sixteenth and seventeenth century,

which delighted Chenal, and I was finally induced

to sing my sailor songs which Poulenc played for me.

Poulenc's Tante Lena was invited to the Opera also

and asked us if we would like to come and dress

at her flat at Cannes. She was the sweetest old lady

I have ever met, very active and talkative, and was

so kind and nice to me, treating me as if I wasayoung

thing of twenty. She came and brushed my hair

and helped me to dress and we all went to the

Cafe de Paris and dined. I really did feel like a

jeune file being chaperoned and out for the first

time. I wore a magnificent white dress with white

beads on it, very long. My hair was cut quite short

with two side whiskers, known by the apaches as

Rouflaquettes. I had enormous pearl earrings, a

large pearl ring, and a very good imitation gold

chain bracelet, all of which had been given to me

by R., F., and Poulenc one day, when they left

me alone at the Cafe de Paris, and went out and

showered false jewellery upon me, with which I

was delighted; and they really looked magnificent

with my fine dress. Chenal was a splendid actress,

but looked really almost too big for the stage.

Afterwards we went to the Casino and had supper

with Ghenal and Picabia and his wife and several

other people. I induced Picabia to dance. He

assured me that he had never done so before, but

he got round somehow. He was much shorter than

I was, and rather fat.

Chenal hired a motor-boat sometimes and took

her friends to the smaller of the two islands opposite

Cannes, called St. Marguerite. She invited us all to

lunch with her one day. F. was not feeling well and

so Poulenc and I went off in the car together. We

had to meet at a small cafe and had to explain that

F. could not come. One motor went back and

Poulenc and I got into ChenaFs Hispano-Suiza,

which was very large and grand. There were

Picabia and Gaby and two other people. It was a

beautiful day and very hot. On the island is a little

restaurant by the sea and under some trees we had

the spfaialiti de la maison, which was lobsters done

in a special way. Everyone was French except

myself. From St. Marguerite we could see In the

distance, in the Golfe Juan, some warships. We were

told that they were English.

After lunch we visited

After lunch we visited a monastery and then took our motor-boat. Ghenal

suggested that as we had plenty of time we should

return by the Golf Juan

and visit the warships. The

and visit the warships. The first one had not a visitors 5 day, but the second one

was the " Royal Oak," and we climbed up the side.

A petty officer said to a sailor who had helped us up,

" Do they speak English? " And I said, " I am

English," whereupon they were delighted. So were

my friends, and we saw all over the gun-room and

climbed up and down ladders. When we got to

Cannes we went to the Casino. One can play boule

without a special ticket, but for the roulette and

more serious gambling rooms one has to have one.

Chenal was charming and bought me a season ticket

for a month, not that I ever gambled, but it was

most thrilling to watch the faces of the Greeks and

serious old ladies at the most serious table of all,

where the chips on the table staggered me. We

saw the ex-King of Portugal. We had to wait

a little before the really serious table started. On

each place is a card with a name on it, and I saw

the names of several very well-known people.

Eventually the table filled up. There was a very

smart old lady with a large hat covered in flowers.

She had the most sinister face I have ever seen, and

completely expressionless. There were two elderly

Englishwomen, who looked like governesses, and had

piles of chips in front of them. Poulenc played

boule, I did not play anything, but continued to

watch the roulette. Our motor came to fetch us,

and Poulenc and I drove back to the Chateau.

The next day we had arranged to meet Stravinsky,

who was to have lunch with us at Faletto's

No comments:

Post a Comment