Richard Sharpe and the Invasion of France, June to November 1813. Major Richard Sharpe,s men were in mortal

Richard Sharpe and the Invasion of France, June to November 1813. Major Richard Sharpe,s men were in mortal  danger - not from the French, but from the bureaucrats of Whitehall. Unless reinforcements could be brought from England, the depleted South Essex would be disbanded,

danger - not from the French, but from the bureaucrats of Whitehall. Unless reinforcements could be brought from England, the depleted South Essex would be disbanded, their troops scattered throughout the army. Determined not to see his regiment die, Sharpe returns to England and uncovers a nest of well-bred, high-ranking traitors, any one of whom could utterly destroy his career with a word, or a stroke of the pen. Sharpe is forced into the most desperate gamble of his life - and not even the influence of the Prince Regent may be enough to save him...Seventh volume in the Richard Sharpe Napoleonic Wars saga, about a former enlisted man who won a battlefield commission at the battle of Talavera in 1809, has spent six volumes fighting the Peninsular campaign in Spain and Portugal and has at last, under

their troops scattered throughout the army. Determined not to see his regiment die, Sharpe returns to England and uncovers a nest of well-bred, high-ranking traitors, any one of whom could utterly destroy his career with a word, or a stroke of the pen. Sharpe is forced into the most desperate gamble of his life - and not even the influence of the Prince Regent may be enough to save him...Seventh volume in the Richard Sharpe Napoleonic Wars saga, about a former enlisted man who won a battlefield commission at the battle of Talavera in 1809, has spent six volumes fighting the Peninsular campaign in Spain and Portugal and has at last, under  Wellington, invaded France in mid-1813. Sharpe is now a major, but attrition has reduced his famed South Essex regiment to half. strength, and no replacements are being sent to the regiment's Spanish bivouac. What's worse, news is that his South Essex regiment soon will be disbanded and his battle-seasoned troops drawn off into other regiments.

Wellington, invaded France in mid-1813. Sharpe is now a major, but attrition has reduced his famed South Essex regiment to half. strength, and no replacements are being sent to the regiment's Spanish bivouac. What's worse, news is that his South Essex regiment soon will be disbanded and his battle-seasoned troops drawn off into other regiments.  This is too much for Sharpe to bear, especially since his regiment was distinguished for capturing the first eagle insigne from a French flag in the war against Napoleon. Accompanied by his faithful Irish giant Sergeant Harper, Sharpe sails to England to find out for himself the best way to snatch his regiment from the jaws of bureaucracy. A companion regiment stationed in England, from which he had hoped to draw troops, suddenly doesn't exist - except on paper. Everywhere that Sharpe hunts for it proves a blind alley. Somebody is carrying on a tremendous cover up and milking the War Office for gold to support a literally invisible regiment. To find out where this hidden pool of troops might be, Sharpe and Harper strip themselves of their uniforms and pass themselves off as old soldiers ready to reenlist in the missing regiment. A recruiting sergeant, in a dreadfully oppressive scene, indeed signs them up along with other recruits and ships them off to boot camp, This turns out to be a hidden mudhole on Foulness island,

This is too much for Sharpe to bear, especially since his regiment was distinguished for capturing the first eagle insigne from a French flag in the war against Napoleon. Accompanied by his faithful Irish giant Sergeant Harper, Sharpe sails to England to find out for himself the best way to snatch his regiment from the jaws of bureaucracy. A companion regiment stationed in England, from which he had hoped to draw troops, suddenly doesn't exist - except on paper. Everywhere that Sharpe hunts for it proves a blind alley. Somebody is carrying on a tremendous cover up and milking the War Office for gold to support a literally invisible regiment. To find out where this hidden pool of troops might be, Sharpe and Harper strip themselves of their uniforms and pass themselves off as old soldiers ready to reenlist in the missing regiment. A recruiting sergeant, in a dreadfully oppressive scene, indeed signs them up along with other recruits and ships them off to boot camp, This turns out to be a hidden mudhole on Foulness island, where Sharpe and Harper go through weeks of brutal training as recruits. Eventually, they escape from the island and pursue the trail of graft into the highest levels of the court before returning to their regiment with the needed troops and gearing up for the invasion of France. Livelier than usual, in fact quite original in that Sharpe gives up his command and finds himself in the foulest, pest-ridden depths of army life.

where Sharpe and Harper go through weeks of brutal training as recruits. Eventually, they escape from the island and pursue the trail of graft into the highest levels of the court before returning to their regiment with the needed troops and gearing up for the invasion of France. Livelier than usual, in fact quite original in that Sharpe gives up his command and finds himself in the foulest, pest-ridden depths of army life.

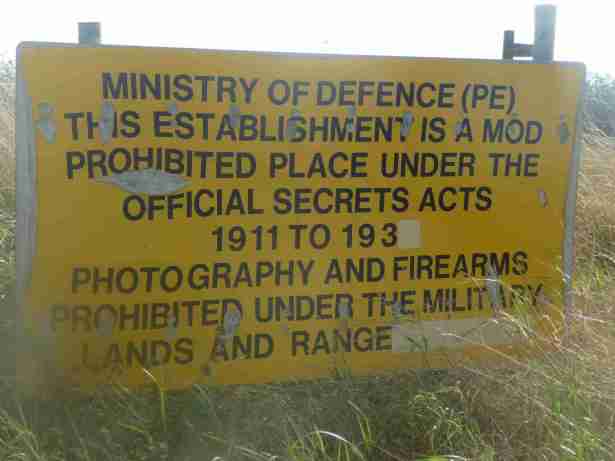

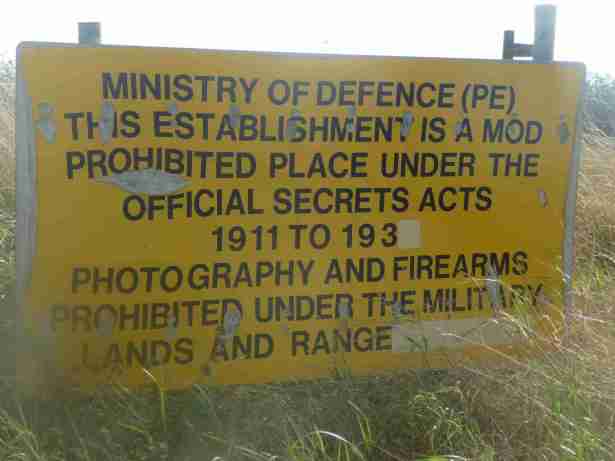

From 1855, the Shoebury Sands, which are a continuation of the Maplin Sands to the south of the island, had been used as an artillery testing site, and the War Office sought to extend this at the end of the 19th century, by buying the island and its offshore sands, to act as a research and development centre for new weapons. They bought some of the sands above Fisherman's Head in 1900, but the rest belonged to Alan Finch, the Lord of the Manor, and he refused to grant shooting rights over them. In 1912, the War Office also discovered that large areas of the sands were leased to tenants, who used them for fishing kiddles.

A kiddle was a large V-shaped or square net, which formed an enclosure in which fish were trapped as the tide receded.

Attempts to buy the lordship were also refused by Finch, but he died in 1914, and his half-brother Wilfred Henry Montgomery Finch sold it on 13 July 1915, resulting in the War Office owning around two-thirds of the island. They had also been buying any farms that were not part of the manor, and by the end of the First World War

the only buildings which they did not own were the church and rectory, the school, and a mission hall at Courts End. They demolished the post mill

towards the beginning of the war, and the parish poor-house and a wooden lock-up which was located near the church were also demolished.

towards the beginning of the war, and the parish poor-house and a wooden lock-up which was located near the church were also demolished.

Ian Yearsley, in

Islands of Essex opens the chapter on Foulness with a portentous quote from James Wentworth Day who describes “…that strange island where no stranger is welcome, where all unknown faces are suspect…”.Our experience is rather the opposite, although, with a time-frame of only four hours, it would be hard to outstay your welcome. A tractor pulls up outside the centre, towing a contraption that is something between a bathing machine and a very small

railway carriage, out of which about a dozen people emerge. It turns out that they have just travelled the B

to get here, and we submit a couple of the guys to a friendly interrogation. It has taken them about an hour to travel from Wakering Stairs,

and they enthuse about the experience of travelling over the Maplin sands,

a mile or so from the shoreline.

They are only half the party, the other half are doing it on foot. We meet Brian and the local farmer who organise the trip, and they too are incredibly enthusiastic about their project, Foulness is, Brian asserts, his favourite place in Essex. The tractor is normally used for fishing. The farmer takes it onto the sands, sets it in a slow automatic gear so that it retreats at the same speed as the tide whilst he fishes from a trailer on the back. We talk about the dangers of walking the Broomway. Despite Robert Macfarlane describing it as a ‘cakewalk’ (retrospectively) in his book

The Old Ways, I feel it needs to be approached with respect. They are more than happy to regale us with tales of the path; of the fisherman who, recently, was so intent on digging for ragworm on the sands that he didn’t notice the sea mist roll in until it was too late, and found himself in a complete white-out. Fortunately, he had followed the traditional local advice of dragging his fork behind him to leave a trail that he could follow back to safety. Then, going back some years, there was the vicar who, returning late from a visit to a colleague in London with a rucksack full of books for the island school, set out upon the path in the dark, missed his bearings, and had to summon all his knowledge of the local lights and topography to find his way back the shore, but nearly died of hypothermia. The books remained safe, but from then on, the vicar advised all travelling to Foulness to go via Burnham and catch a ferry to the north of the island. The apparent flatness of the Maplin Sand when viewed from the shore is deceptive; It can form dunes tall enough that you would lose sight of the horizon and be invisible from the shore. The pockets of quicksand that border the path are known locally as ‘coffins'; “The quicksand won’t kill you”, Brian informs us cheerfully, “you’ll only sink up to your waist, it’s the incoming tide that will get you.”

We head back to the security gate, check out and turn on to the public road that leads to Wakering Stairs, the start of the Broomway. Having looked at many photos and film clips of the Broomway, the ramp to the seawall, with an empty watchtower next to it, feels familiar. A family is picnicking on the wall and when we reach the top of the ramp, the Maplin Sands shimmer before us, stretching out to where the Thames heads for the sea a couple of miles away, and beyond that,

the Kent Coast, presumably Sheppey and Whitstable Bay.

We walk over the semi-made causeway, which peters out after a hundred yards or so. There are a couple of cyclists out on the mud ahead of us, and tractor tracks, presumably left by the vehicle we had met at Churchend, so we proceed with confidence. Sound behaves oddly. The voices of the people on the shore carry clearly and invisible geese honk from a distance over the mudflats. The best account of the Broomway that I have read appears in The Old Ways in which Macfarlane describes the ‘soft lunacy’ of the walk across the ‘mirror world’ of this seascape, and the lure of the horizon, with “as potent a pull upon the mind as a mountain’s summit”. He and his companion stray from the notional safety of the path and walk two miles out across the sands. We have come barely a half mile from the stairs, although Ebb Tide appears to be in thrall to the potent pull and has struck off a couple of hundred yards ahead of the four of us. The tide is due to be flowing in: Master F. notices some of the pools covering the sand have an incoming, trickling mini-current in them, and mindful of advice that the tide here can move faster than a person can run,and not being runners, we hail Ebb Tide and head for the shore.

towards the beginning of the war, and the parish poor-house and a wooden lock-up which was located near the church were also demolished.

towards the beginning of the war, and the parish poor-house and a wooden lock-up which was located near the church were also demolished. railway carriage, out of which about a dozen people emerge. It turns out that they have just travelled the B

railway carriage, out of which about a dozen people emerge. It turns out that they have just travelled the B to get here, and we submit a couple of the guys to a friendly interrogation. It has taken them about an hour to travel from Wakering Stairs,

to get here, and we submit a couple of the guys to a friendly interrogation. It has taken them about an hour to travel from Wakering Stairs,  and they enthuse about the experience of travelling over the Maplin sands,

and they enthuse about the experience of travelling over the Maplin sands, a mile or so from the shoreline.

a mile or so from the shoreline.  to get here, and we submit a couple of the guys to a friendly interrogation. It has taken them about an hour to travel from Wakering Stairs,

to get here, and we submit a couple of the guys to a friendly interrogation. It has taken them about an hour to travel from Wakering Stairs,  the Kent Coast, presumably Sheppey and Whitstable Bay.

the Kent Coast, presumably Sheppey and Whitstable Bay.

No comments:

Post a Comment