.  Edgar Hoover was born on New Year's Day 1895 in Washington, D.C., to Anna Marie (née

Edgar Hoover was born on New Year's Day 1895 in Washington, D.C., to Anna Marie (née  Scheitlin; 1860–1938), who was ofGerman Swiss descent, and Dickerson Naylor Hoover, Sr. (1856–1921), of English and German ancestry. The uncle of Hoover's mother was a Swiss honorary consul general to the United States. Hoover did not have a birth certificate filed,

Scheitlin; 1860–1938), who was ofGerman Swiss descent, and Dickerson Naylor Hoover, Sr. (1856–1921), of English and German ancestry. The uncle of Hoover's mother was a Swiss honorary consul general to the United States. Hoover did not have a birth certificate filed, although it was required in 1895 Washington. Two siblings had certificates. Hoover's was not filed until 1938, when he was 43.

although it was required in 1895 Washington. Two siblings had certificates. Hoover's was not filed until 1938, when he was 43.

One man made the G-men legendary, turned a bumbling FBI into what was perceived to be an army of truth and justice known the world over, and made himself a towering American legend: J. Edgar Hoover. For nearly 50 years, he ran the FBI. As the gatekeeper of its secrets, its power and its image, Hoover kept the keys to a kingdom called Washington.

For nearly 50 years, he ran the FBI. As the gatekeeper of its secrets, its power and its image, Hoover kept the keys to a kingdom called Washington.

Of course today, the Hoover legend is not just about crime fighting. It has as much to do with playing fast and loose with civil liberties, with collecting vast secret files on innocent people — a powerful man with secrets of his own, including rumors of bizarre sexual behavior. Finding the real J. Edgar Hoover has been the passion of author Richard Hack for nearly two decades, leading him to write the book, “Puppet Master: The Secret life of J. Edgar Hoover."His towering profile in Washington was based in part on nobody calling his bluff, just like the Bush family at the moment Hoover played his signature high stakes poker with an astounding eight presidents from 1924 until his death in 1972.

with collecting vast secret files on innocent people — a powerful man with secrets of his own, including rumors of bizarre sexual behavior. Finding the real J. Edgar Hoover has been the passion of author Richard Hack for nearly two decades, leading him to write the book, “Puppet Master: The Secret life of J. Edgar Hoover."His towering profile in Washington was based in part on nobody calling his bluff, just like the Bush family at the moment Hoover played his signature high stakes poker with an astounding eight presidents from 1924 until his death in 1972. No FBI head will ever again have the power Hoover had. The portrait that emerges is of Hoover the good, Hoover the bad, and

No FBI head will ever again have the power Hoover had. The portrait that emerges is of Hoover the good, Hoover the bad, and Hoover a man with a taste for the ugly side of power. It was the good Hoover whose experience as a clerk at the Department of Justice helped him turn a disorganized federal agency into a true crime fighting organization.When he came to the FBI — or Bureau of Investigation then —

Hoover a man with a taste for the ugly side of power. It was the good Hoover whose experience as a clerk at the Department of Justice helped him turn a disorganized federal agency into a true crime fighting organization.When he came to the FBI — or Bureau of Investigation then — his mandate was to clean it up and make it legitimate. And if there's one thing that he did was to start to catalogue everything, keep everything organized.

his mandate was to clean it up and make it legitimate. And if there's one thing that he did was to start to catalogue everything, keep everything organized.

above Exploitation auteur Larry Cohen’s unjustly forgotten labor-of-love biopic gets resurrected again this year, in honor of the release of Clint Eastwood’s Leo-for-the-Oscar! vehicle.

That organization included the introduction of fingerprint files, crime labs, and of course there were the agents themselves. Hoover insisted they be educated, dedicated to their job, and dedicated to him.All of this team of men were loyal only to him. They answered only to him. They didn't answer to the

dedicated to him.All of this team of men were loyal only to him. They answered only to him. They didn't answer to the  Attorney General. They didn't answer to the President of the United States, who had Secret Service.

Attorney General. They didn't answer to the President of the United States, who had Secret Service. They answered to Hoover, period.The insight that he had was that if you weren't elected it was far better.

They answered to Hoover, period.The insight that he had was that if you weren't elected it was far better. He created a mystique about himself that the people would not allow him to leave.Hoover's mystique came from a mastery of modern public relations long before official Washington even knew what that was.

He created a mystique about himself that the people would not allow him to leave.Hoover's mystique came from a mastery of modern public relations long before official Washington even knew what that was. Hoover brought Madison Avenue to Pennsylvania Avenue. Hoover ran the FBI, but he managed its image everywhere,

Hoover brought Madison Avenue to Pennsylvania Avenue. Hoover ran the FBI, but he managed its image everywhere,  He dictated to Hollywood. And the studios followed Hoover's orders of how crime and punishment should be portrayed.He looked at everything.

He dictated to Hollywood. And the studios followed Hoover's orders of how crime and punishment should be portrayed.He looked at everything. He looked at every movie, every reference, every scene, every actor. He approved it all. And he did. In the ‘FBI Story’ that starred Jimmy Stewart, he cleared Jimmy Stewart for instance. He interviewed him, gave his okay.And then there was James Cagney.

He looked at every movie, every reference, every scene, every actor. He approved it all. And he did. In the ‘FBI Story’ that starred Jimmy Stewart, he cleared Jimmy Stewart for instance. He interviewed him, gave his okay.And then there was James Cagney. Hack says Hoover was not thrilled that Cagney portrayed criminals in movies like “Public Enemy.His only advice to

Hack says Hoover was not thrilled that Cagney portrayed criminals in movies like “Public Enemy.His only advice to  Cagney was always, ‘Get killed by the end, make sure you're dead because I don’t want to see any crooks living.Hoover more than got his way as Cagney went clean

Cagney was always, ‘Get killed by the end, make sure you're dead because I don’t want to see any crooks living.Hoover more than got his way as Cagney went clean , switching from playing gangsters to playing G-Men. Hoover even cast himself in films. Hoover was perhaps most controlling of his own image.

, switching from playing gangsters to playing G-Men. Hoover even cast himself in films. Hoover was perhaps most controlling of his own image. A life-long bachelor, his immunity to personal scandal while in office, came, says Hack, from sacrificing his own personal life.But still, there was gossip.

A life-long bachelor, his immunity to personal scandal while in office, came, says Hack, from sacrificing his own personal life.But still, there was gossip. Hoover's only companion seemed to be his second in command at the Bureau, Clyde Tolson.

Hoover's only companion seemed to be his second in command at the Bureau, Clyde Tolson.

Hoover felt insulted by the civil rights leader. King dared to ignore a Hoover phone call.From that one unanswered phone call, the rest of King's life, Dr. King did not have a free moment from the specter of J. Edgar Hoover, ever. He tapped him, he followed him.Hoover collected intimate details on King's private life, details that would haunt and embarrass King's family for years to come. Hoover in some sense was jealous of Martin Luther King.

He tapped him, he followed him.Hoover collected intimate details on King's private life, details that would haunt and embarrass King's family for years to come. Hoover in some sense was jealous of Martin Luther King.

He had a wife, he had a family, he had authority, he had respect. He had everything and Hoover was definitely jealous.

Robert Kennedy made Hoover turn his attention away from fighting communism to organized crime, which Hoover, at that time, believed was much less of a threat.

Hoover's career nearly came to an end with Kennedy but He didn't fire Hoover because he didn't know what Hoover really knew. The same reason no one else fired Hoover. When it really came down to it.When it came to the Kennedy clan, Hoover perhaps felt the most contempt for Attorney General Robert Kennedy.He considered him an outrage. He thought he was a loose cannon he could not control and he loved being in control.He had nudes of many people. There was an obscene file that he kept himself.”

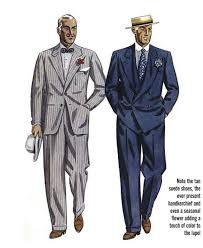

World War II spurred a number of trends in casual jacket styles. The Eisenhower/battle jacket (pictured above in the left image) was a short, waist-length bloused jacket with an attached band or belt of the same fabric. Worn by Dwight D. Eisenhower during the war, versions of this jacket turn up in both men's and women's wear.Other overcoat styles worn during the 1920s, 30s and 40s included: pea coats (double breasted, dark, boxy jackets worn by American sailors), raccoon coats (the mark of a "successful" collegian), Chesterfields (wool overcoats with velvet upper collars),English guard's coats (dark-blue coats with wide lapels, an inverted pleat at center back and a half belt), polo coats (tan camel's hair coats initially worn by the English polo team playing matches in the US. Generally double breasted with a six button closure) andbush jackets (short sleeved tan cotton jackets with four large flapped pockets made to imitate styles worn by hunters and explorers in Africa).

World War II spurred a number of trends in casual jacket styles. The Eisenhower/battle jacket (pictured above in the left image) was a short, waist-length bloused jacket with an attached band or belt of the same fabric. Worn by Dwight D. Eisenhower during the war, versions of this jacket turn up in both men's and women's wear.Other overcoat styles worn during the 1920s, 30s and 40s included: pea coats (double breasted, dark, boxy jackets worn by American sailors), raccoon coats (the mark of a "successful" collegian), Chesterfields (wool overcoats with velvet upper collars),English guard's coats (dark-blue coats with wide lapels, an inverted pleat at center back and a half belt), polo coats (tan camel's hair coats initially worn by the English polo team playing matches in the US. Generally double breasted with a six button closure) andbush jackets (short sleeved tan cotton jackets with four large flapped pockets made to imitate styles worn by hunters and explorers in Africa).

He had things no one else could have, knew things no one else could know. For him ordinary rules did not apply. Until the end, Hoover actually believed he was America's ultimate protector, something America believed for awhile.Will there ever be another J. Edgar Hoover? Of course , America is based on people like Hoover, Cross dreesers not only but traitors .In Schaumburg, Illinois,

a grade school was named after Hoover. In 1994, after personal information about Hoover was released, the school's name was changed to reflect Herbert Hoover instead of J. Edgar Hoover. John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was the first Director of the Federal Bureau of

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was the first Director of the Federal Bureau of  Investigation (FBI) of the United States. Appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation

Investigation (FBI) of the United States. Appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation —predecessor to the FBI—in 1924, he was instrumental in founding the FBI in 1935, where he remained director until his

—predecessor to the FBI—in 1924, he was instrumental in founding the FBI in 1935, where he remained director until his death in 1972 at age 77. Hoover is credited with building the FBI into a large and efficient crime-fighting agency, and with instituting a

death in 1972 at age 77. Hoover is credited with building the FBI into a large and efficient crime-fighting agency, and with instituting a  number of modernizations to police technology, such as a centralized fingerprint file and forensic laboratories.

number of modernizations to police technology, such as a centralized fingerprint file and forensic laboratories.

Late in life and after his death Hoover became a controversial figure, as evidence of his secretive actions became known. His critics have accused him of exceeding the jurisdiction of the FBI.

actions became known. His critics have accused him of exceeding the jurisdiction of the FBI.  He used the FBI to harass political dissenters and activists, to amass secret files on political leaders, and to collect evidence using illegal methods.

He used the FBI to harass political dissenters and activists, to amass secret files on political leaders, and to collect evidence using illegal methods. Hoover consequently amassed a great deal of power and was in a position to intimidate and threaten sitting Presidents. According to President Harry S Truman,

Hoover consequently amassed a great deal of power and was in a position to intimidate and threaten sitting Presidents. According to President Harry S Truman, The szuit worn by the man who shot Dillinger

The szuit worn by the man who shot Dillinger

Hoover transformed the FBI into his private secret police force; Truman stated that "we want no Gestapo or secret police. FBI is tending in that direction. They are dabbling in sex-life scandals and plain blackmail...Edgar Hoover would give his right eye to take over, and all congressmen and senators are afraid of him".

They are dabbling in sex-life scandals and plain blackmail...Edgar Hoover would give his right eye to take over, and all congressmen and senators are afraid of him".

J. Edgar Hoover was born on New Year's Day 1895 in Washington, D.C., to Anna Marie (née Scheitlin; 1860–1938),

J. Edgar Hoover was born on New Year's Day 1895 in Washington, D.C., to Anna Marie (née Scheitlin; 1860–1938),  who was of German Swiss descent, and Dickerson Naylor Hoover, Sr. (1856–1921), of English and German ancestry.

who was of German Swiss descent, and Dickerson Naylor Hoover, Sr. (1856–1921), of English and German ancestry. The uncle of Hoover's mother was a Swiss honorary consul general to the United States. Hoover did not have a birth certificate filed, although it was required in 1895 Washington.

The uncle of Hoover's mother was a Swiss honorary consul general to the United States. Hoover did not have a birth certificate filed, although it was required in 1895 Washington. Two siblings had certificates. Hoover's was not filed until 1938, when he was 43.

Two siblings had certificates. Hoover's was not filed until 1938, when he was 43.

Hoover grew up near the Eastern Market in Washington's Capitol Hill neighborhood. At Central High, he sang in the school choir, participated in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps program, and competed on the debate team, where he argued against women getting the right to vote and against the abolition of the death penalty.The school newspaper applauded his "cool, relentless logic".

in Washington's Capitol Hill neighborhood. At Central High, he sang in the school choir, participated in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps program, and competed on the debate team, where he argued against women getting the right to vote and against the abolition of the death penalty.The school newspaper applauded his "cool, relentless logic".

He obtained a law degree from George Washington University Law School in 1916 where he was a member of the Alpha Nu Chapter of the Kappa Alpha Order and an LL.M., a Master of Laws degree, in 1917 from the same university. While a law student, Hoover became interested in the career of Anthony Comstock,

While a law student, Hoover became interested in the career of Anthony Comstock, the New York City United States Postal Inspector, who waged prolonged campaigns against fraud and vice, and also was against pornography and birth control.

the New York City United States Postal Inspector, who waged prolonged campaigns against fraud and vice, and also was against pornography and birth control.

Hoover lived in Washington, D.C., for his entire life.

Immediately after getting his degree, Hoover was hired by the Justice Department to work in the War Emergency Division. He soon became the head of the Division's Alien Enemy Bureau , authorized by President Wilson at the beginning of World War I to arrest and jail disloyal foreigners

, authorized by President Wilson at the beginning of World War I to arrest and jail disloyal foreigners  without trial. He received additional authority from the 1917 Espionage Act. Out of a list of 1400 suspicious Germans living in the U.S., the Bureau arrested 98 and designated 1,172 as arrestable.

without trial. He received additional authority from the 1917 Espionage Act. Out of a list of 1400 suspicious Germans living in the U.S., the Bureau arrested 98 and designated 1,172 as arrestable.

In August 1919, Hoover became head of the Bureau of Investigation's new General Intelligence Division—also known as the Radical Division because its goal was to monitor and disrupt the work of domestic radicals.

Hoover became head of the Bureau of Investigation's new General Intelligence Division—also known as the Radical Division because its goal was to monitor and disrupt the work of domestic radicals.

America's First Red Scare was beginning, and one of Hoover's first assignments was to carry out the Palmer Raids.

The Palmer Raids were attempts by the United States Department of Justice to arrest and deport radical leftists, especially anarchists, from the United States. DOROTHY LAMOUR interested Hoover for some reason

DOROTHY LAMOUR interested Hoover for some reason

The raids and arrests occurred in November 1919 and January 1920 under the leadership of Attorney

1920 under the leadership of Attorney  General A. Mitchell Palmer. Though more than 500 foreign citizens were deported, including a number of prominent leftist

General A. Mitchell Palmer. Though more than 500 foreign citizens were deported, including a number of prominent leftist  leaders, Palmer's efforts were largely frustrated by officials at the U.S. Department of Labor who had responsibility for deportations and who objected to Palmer's methods. The Palmer Raids occurred in the larger context of the Red Scare, the term given to fear of and reaction against political radicals in the U.S. in the years immediately following World War I.

leaders, Palmer's efforts were largely frustrated by officials at the U.S. Department of Labor who had responsibility for deportations and who objected to Palmer's methods. The Palmer Raids occurred in the larger context of the Red Scare, the term given to fear of and reaction against political radicals in the U.S. in the years immediately following World War I.

Hoover and his chosen assistant, George Ruch monitored a variety of U.S. radicals with the intent to punish, arrest, or deport them. Targets during this period included Marcus Garvey ; Rose Pastor Stokes

; Rose Pastor Stokes and Cyril Briggs; Emma Goldman

and Cyril Briggs; Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman;

and Alexander Berkman;  and future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter

and future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter , whom Hoover maintained was "the most dangerous man in the United States".

, whom Hoover maintained was "the most dangerous man in the United States".

In 1921, he rose in the Bureau of Investigation to deputy head, and in 1924, the Attorney General made him the acting director. On May 10, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge appointed Hoover as the sixth director of the Bureau of Investigation, following President Warren Harding's

President Calvin Coolidge appointed Hoover as the sixth director of the Bureau of Investigation, following President Warren Harding's death and in response to allegations that the prior director, William J. Burns, was involved in the Teapot Dome scandal. When Hoover took over the Bureau of Investigation, it had approximately 650 employees, including 441 Special Agents.

death and in response to allegations that the prior director, William J. Burns, was involved in the Teapot Dome scandal. When Hoover took over the Bureau of Investigation, it had approximately 650 employees, including 441 Special Agents.

Hoover was noted as sometimes being capricious in his leadership; he frequently fired FBI agents, singling out those who he thought "looked stupid like truck drivers" or he considered to be "pinheads". He also relocated agents who had displeased him to career-ending assignments and locations. Melvin Purvis

or he considered to be "pinheads". He also relocated agents who had displeased him to career-ending assignments and locations. Melvin Purvis  was a prime example; he was one of the most effective agents in capturing and breaking up 1930s gangs

was a prime example; he was one of the most effective agents in capturing and breaking up 1930s gangs  and received substantial public recognition, but a jealous Hoover maneuvered him out of the FBI.

and received substantial public recognition, but a jealous Hoover maneuvered him out of the FBI.

Hoover often hailed local law-enforcement officers around the country and built up a national network of supporters and admirers in the process. One that he often commended was the conservative sheriff of Caddo Parish , Louisiana, J. Howell Flournoy,

, Louisiana, J. Howell Flournoy, for particular effectiveness.

for particular effectiveness.

In the early 1930s, criminal gangs carried out large numbers of bank robberies in the Midwest. They used their superior firepower and fast getaway cars to elude local law enforcement agencies and avoid arrest. Many of these criminals, particularly John Dillinger, who became famous for leaping over bank cages and repeatedly escaping from jails and police traps, frequently made newspaper headlines across the United States.

who became famous for leaping over bank cages and repeatedly escaping from jails and police traps, frequently made newspaper headlines across the United States. Since the robbers operated across state lines, their crimes became federal offenses, giving Hoover and his men the authority to pursue them. Initially, the FBI suffered some embarrassing foul-ups, in particular with

Since the robbers operated across state lines, their crimes became federal offenses, giving Hoover and his men the authority to pursue them. Initially, the FBI suffered some embarrassing foul-ups, in particular with  Dillinger and his conspirators. A raid on a summer lodge named "Little Bohemia"

Dillinger and his conspirators. A raid on a summer lodge named "Little Bohemia" in Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin

in Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin , left an FBI agent and a civilian bystander dead, and others wounded. All the gangsters escaped.

, left an FBI agent and a civilian bystander dead, and others wounded. All the gangsters escaped.  Hoover realized that his job was now on the line, and he pulled out all stops to capture the culprits. In late July 1934, Special Agent Melvin Purvis,

Hoover realized that his job was now on the line, and he pulled out all stops to capture the culprits. In late July 1934, Special Agent Melvin Purvis, the Director of Operations in the Chicago office, received a tip on Dillinger's whereabouts which paid off when Dillinger was located,

the Director of Operations in the Chicago office, received a tip on Dillinger's whereabouts which paid off when Dillinger was located, ambushed and killed by FBI agents outside the Biograph Theater.

ambushed and killed by FBI agents outside the Biograph Theater.

In the same period, there were numerous Mafia shootings as a result of Prohibition, while Hoover continued to deny the very existence of organized crime. Frank Costello helped encourage this view by feeding Hoover, "an inveterate horseplayer" known to send Special Agents to place $100 bets for him, tips on sure winners through their mutual friend, gossip columnist Walter

to deny the very existence of organized crime. Frank Costello helped encourage this view by feeding Hoover, "an inveterate horseplayer" known to send Special Agents to place $100 bets for him, tips on sure winners through their mutual friend, gossip columnist Walter  Winchell. Hoover said the Bureau had "much more important functions" than arresting bookmakers and gamblers.

Winchell. Hoover said the Bureau had "much more important functions" than arresting bookmakers and gamblers.

Even though he was not there, Hoover was credited with several highly publicized captures or shootings of outlaws and bank robbers. These included that of Dillinger, Alvin Karpis , and Machine Gun Kelly,

, and Machine Gun Kelly, which led to the Bureau's powers being broadened and it was given its new name in 1935: the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In 1939, the FBI became pre-eminent in the field of domestic intelligence.

which led to the Bureau's powers being broadened and it was given its new name in 1935: the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In 1939, the FBI became pre-eminent in the field of domestic intelligence.  made changes, such as expanding and combining fingerprint files in the Identification Division to compile the largest collection of fingerprints to date Hoover also helped to expand the FBI's recruitment and create the FBI Laboratory, a division established in 1932 to examine evidence found by the FBI.

made changes, such as expanding and combining fingerprint files in the Identification Division to compile the largest collection of fingerprints to date Hoover also helped to expand the FBI's recruitment and create the FBI Laboratory, a division established in 1932 to examine evidence found by the FBI.

Hoover, perhaps at the behest of Richard Nixon, investigated ex-Beatle John Lennon by putting the singer under surveillance, and Hoover wrote this letter to the Attorney General in 1972. A 25-year battle by historian Jon Wiener under the Freedom of Information Act eventually resulted in the release of documents like this one.

Hoover was concerned about subversion, and under his leadership, the FBI spied upon tens of thousands of suspected subversives and radicals. According to critics,  tended to exaggerate the dangers of these alleged subversives and many times overstepped his bounds in his pursuit of eliminating that perceived threat.

tended to exaggerate the dangers of these alleged subversives and many times overstepped his bounds in his pursuit of eliminating that perceived threat.

The FBI investigated rings of German saboteurs and spies starting in the late 1930s, and had primary responsibility for counterespionage. The first arrests of German agents were made in 1938, and continued throughout World War II. In the Quirin affair during World War II, German U-boats set two small groups of Nazi agents ashore in Florida and Long Island

affair during World War II, German U-boats set two small groups of Nazi agents ashore in Florida and Long Island to cause acts of sabotage within the country. The two teams were apprehended after one of the men contacted the FBI, and told them everything. He was also charged and convicted.

to cause acts of sabotage within the country. The two teams were apprehended after one of the men contacted the FBI, and told them everything. He was also charged and convicted.

During the war and for many years afterward, the FBI maintained a fictionalized version of the story in which it had preempted and caught the saboteurs solely by its own investigations and had even infiltrated the

During the war and for many years afterward, the FBI maintained a fictionalized version of the story in which it had preempted and caught the saboteurs solely by its own investigations and had even infiltrated the

clydes hat

German government. This story was useful during the war to discourage the Germans by making the FBI seem more invincible than it really was, and perhaps afterward to similarly mislead the Soviets; but it also served Hoover himself in his efforts to maintain a superhero-style image for the FBI in American minds.

The FBI participated in the Venona Project, a pre–World War II joint project with the British to eavesdrop on Soviet spies in the UK and the United States. It was not initially realized that espionage was being committed, but due to multiple wartime Soviet use of one-time pad ciphers, which are normally unbreakable,

a pre–World War II joint project with the British to eavesdrop on Soviet spies in the UK and the United States. It was not initially realized that espionage was being committed, but due to multiple wartime Soviet use of one-time pad ciphers, which are normally unbreakable, redundancies were created, enabling some intercepts to be decoded, which established the espionage. Hoover kept the intercepts—America's greatest counterintelligence secret—in a locked safe in his office, choosing not to inform President Truman, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath,

redundancies were created, enabling some intercepts to be decoded, which established the espionage. Hoover kept the intercepts—America's greatest counterintelligence secret—in a locked safe in his office, choosing not to inform President Truman, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath, or two Secretaries of State—Dean Acheson and General George Marshall—while they held office. He informed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the Venona Project in 1952.

or two Secretaries of State—Dean Acheson and General George Marshall—while they held office. He informed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the Venona Project in 1952.

In 1946, U.S. Attorney General Tom C. Clark Hoover to compile a list of potentially disloyal Americans who might be detained during a wartime national emergency. In 1950, at the outbreak of the Korean War, Hoover submitted to President Truman a plan to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and detain 12,000 Americans suspected of disloyalty. Truman did not act on the plan.

Hoover to compile a list of potentially disloyal Americans who might be detained during a wartime national emergency. In 1950, at the outbreak of the Korean War, Hoover submitted to President Truman a plan to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and detain 12,000 Americans suspected of disloyalty. Truman did not act on the plan.

In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by Supreme Court decisions that limited the Justice Department's ability to prosecute people for their political opinions, most notably communists. At this time he formalized a covert "dirty tricks" program under the name COINTELPRO.

This program remained in place until it was revealed to the public in 1971, after the theft of many internal documents stolen from an office in Media, Pennsylvania, and was the cause of some of the harshest criticism of Hoover and the FBI. COINTELPRO was first used to disrupt the Communist Party, where Hoover went after targets that ranged from suspected everyday spies to larger celebrity figures such as Charlie Chaplin who were seen as spreading Communist Party propaganda,and later organizations such as the Black Panther Party, Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference and others. Its methods included infiltration, burglaries, illegal wiretaps, planting forged documents and spreading false rumors about key members of target organizations.

Some authors have charged that COINTELPRO methods also included inciting violence and arranging murders. In 1975, the activities of COINTELPRO were investigated by the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, called the Church Committee after its chairman, Senator Frank Church -Idaho), and these activities were declared illegal and contrary to the Constitution.

Hoover amassed significant power by collecting files containing large amounts of compromising and potentially embarrassing information on many powerful people, especially politicians. According to Laurence Silberman, appointed Deputy Attorney General in early 1974, FBI Director Clarence M. Kelley thought such files either did not exist or had been destroyed.

thought such files either did not exist or had been destroyed.

After The Washington Post broke a story in January 1975, Kelley searched and found them in his outer office. The House Judiciary Committee then demanded that Silberman testify about them.

Kelley searched and found them in his outer office. The House Judiciary Committee then demanded that Silberman testify about them.

In 1956, several years before he targeted King, Hoover had a public showdown with T.R.M. Howard, a civil rights leader from Mound Bayou, Mississippi. During a national speaking tour, Howard had criticized the FBI's failure to thoroughly investigate the racially motivated murders of George W. Lee, Lamar Smith, and Emmett Till. Hoover wrote an open letter to the press singling out these statements as "irresponsible."

During a national speaking tour, Howard had criticized the FBI's failure to thoroughly investigate the racially motivated murders of George W. Lee, Lamar Smith, and Emmett Till. Hoover wrote an open letter to the press singling out these statements as "irresponsible."

The Apalachin Meeting of late 1957 changed this; it embarrassed the FBI by proving on newspaper front pages that a nationwide mafia syndicate thrived unimpeded by the nation's "top cops". Hoover immediately changed tack, and during the next five years, the FBI investigated organized crime heavily. Its concentration on the topic fluctuated in subsequent decades, but it never again merely ignored this category of crime.

Hoover's moves against people who maintained contacts with subversive elements, some of whom were members of the civil rights movement, also led to accusations of trying to undermine their reputations. The treatment of Martin Luther King, Jr. and actress Jean Seberg are two examples

.In late August 1979, Seberg disappeared. Her partner, Ahmed Hasni, told police that they had gone to a movie the night of August 30 and when he awoke the next morning, Seberg was gone. After Seberg went missing, Hasni told police that he knew she was suicidal for some time. He claimed that she had attempted suicide in July 1979 by jumping in front of a Paris subway train.

Paris, France. Jacqueline Kennedy recalled that Hoover told President John F. Kennedy that King tried to arrange a sex party while in the capital for the March on Washington and told Robert Kennedy that King made derogatory comments during the President's funeral. Hoover, despite maintaining a public persona of a noble man, was privately racist and was not enthused about racial integration. After trying for a while to trump up evidence that would smear King as being influenced by communists, he discovered that King had a weakness for extramarital sex, and switched to this topic for further smears.

Paris, France. Jacqueline Kennedy recalled that Hoover told President John F. Kennedy that King tried to arrange a sex party while in the capital for the March on Washington and told Robert Kennedy that King made derogatory comments during the President's funeral. Hoover, despite maintaining a public persona of a noble man, was privately racist and was not enthused about racial integration. After trying for a while to trump up evidence that would smear King as being influenced by communists, he discovered that King had a weakness for extramarital sex, and switched to this topic for further smears.

Hoover personally directed the FBI investigation into the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. In 1964, just days before Hoover testified in the earliest stages of the Warren Commission hearings, President Lyndon B. Johnson waived the then-mandatory U.S. Government Service Retirement Age of seventy, allowing Hoover to remain the FBI Director "for an indefinite period of time." The House Select Committee on Assassinations issued a report in 1979 critical of the performance by the FBI, the Warren Commission, and other agencies. The report also criticized what it characterized as the FBI's reluctance to thoroughly investigate the possibility of a conspiracy to assassinate the President.

Hoover's FBI investigated Hollywood lobbyist Jack Valenti, a special assistant and confidant to President Lyndon Johnson, in 1964. Despite Valenti's two-year marriage to Johnson's personal secretary, the investigation focused on rumors that he was having a gay relationship with a commercial photographer friend.

Hoover maintained strong support in Congress until his death at his Washington, D.C., home on May 2, 1972, from a heart attack attributed to cardio-vascular disease.

His body lay in state in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, where Chief Justice Warren Burger eulogized him. President Richard Nixon delivered another eulogy at the funeral service in the National Presbyterian Church. Nixon called Hoover "one of the giants. His long life brimmed over with magnificent achievement and dedicated service to this country which he loved so well."[ Hoover was buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C., next to the graves of his parents and a sister who died in infancy.

where Chief Justice Warren Burger eulogized him. President Richard Nixon delivered another eulogy at the funeral service in the National Presbyterian Church. Nixon called Hoover "one of the giants. His long life brimmed over with magnificent achievement and dedicated service to this country which he loved so well."[ Hoover was buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C., next to the graves of his parents and a sister who died in infancy.

Operational command of the Bureau passed to Associate Director Clyde Tolson. On May 3, Nixon appointed L. Patrick Gray, a Justice Department official with no FBI experience, as Acting Director, with W. Mark Felt remaining as Associate Director.

In 1979, there was a large increase in conflict in the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) under Senator Richard Schweiker, which had re-opened the investigation into the assassination of President Kennedy, reported that Hoover's FBI "failed to investigate adequately the possibility of a conspiracy to assassinate the President". The HSCA further reported that Hoover's FBI "was deficient in its sharing of information with other agencies and departments".

Because Hoover's actions came to be seen as an abuse of power, FBI directors are now limited to one 10-year term,subject to extension by the United States Senate.

The FBI Headquarters in Washington, DC is named after Hoover. Because of the controversial nature of Hoover's legacy, there have been periodic proposals to rename it by legislation proposed by both Republicans and Democrats in the House and Senate. In 2001, Senator Harry Reid sponsored an amendment to strip Hoover's name from the building. "J. Edgar Hoover's name on the FBI building is a stain on the building", Reid said. However, the Senate never adopted the amendment.

President Lyndon B. Johnson at the signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964. White House East Room. People watching include Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Senator Hubert Humphrey, First Lady "Lady Bird Johnson", Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., F.B.I. Director J. Edgar Hoover, Speaker of the House John McCormack. Television cameras are broadcasting the ceremony.

Since the 1940s, rumors have circulated that Hoover was homosexual. The historians John Stuart Cox and Athan G. Theoharis speculated that Clyde Tolson, who became an associate director of the FBI and Hoover's primary heir, may have been his lover.

Hoover hunted down and threatened anyone who made insinuations about his sexuality. He also spread unsubstantiated rumors that Adlai Stevenson was gay to damage the liberal governor's 1952 presidential campaign.His extensive secret files contained surveillance material on Eleanor Roosevelt's alleged lesbian lovers, speculated to be acquired for the purpose of blackmail, as well as material on presidents' liaisons, including those of John F. Kennedy.

Some scholars have dismissed the rumors about Hoover's sexuality, and his relationship with Tolson in particular, as unlikely, while others have described them as probable or even “confirmed”. Still other scholars have reported the rumors without expressing an opinion.

Hoover described Tolson as his alter ego: the men worked closely together during the day and, both single, frequently took meals, went to night clubs and vacationed together. This closeness between the two men is often cited as evidence that they were lovers, though some FBI employees who knew them, such as W. Mark Felt, say that the relationship was “brotherly”. The former FBI official Mike Mason suggested that some of Hoover's colleagues denied that he had a sexual relationship with Tolson in an effort to protect his image

Hoover bequeathed his estate to Tolson, who moved into the house. He accepted the American flag that draped Hoover's casket. Tolson is buried a few yards away from Hoover in the Congressional Cemetery.

Hoover's biographer Richard Hack does not believe that the director was gay. Hack notes that Hoover was romantically linked to actress Dorothy Lamour in the late 1930s and early 1940s, and that after Hoover's death, Lamour did not deny rumors that she had had an affair with Hoover in the years between her two marriages.Hack reported that, during the 1940s and 1950s, Hoover so often attended social events with Lela Rogers, the divorced mother of dancer and actress Ginger Rogers, that many of their mutual friends assumed the pair would eventually marry.

In his 1993 biography Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover, the journalist Anthony Summers quoted "society divorcee" Susan Rosenstiel as claiming to have seen Hoover engaging in cross-dressing in the 1950s at homosexual parties.Summers also said that the Mafia had blackmail material on Hoover, which made Hoover reluctant to aggressively pursue organized crime. Although never corroborated, the allegation of cross-dressing has been widely repeated. In the words of author Thomas Doherty, "For American popular culture, the image of the zaftig FBI director as a Christine Jorgensen wanna-be was too delicious not to savor”

Skeptics of the cross-dressing story point to Susan Rosenstiel's poor credibility (she pled guilty for attempted perjury in a 1971 case and later served time in a New York City jail). Recklessly indiscreet behavior by Hoover would have been totally out of character, whatever his sexuality. Most biographers consider the story of Mafia blackmail to be unlikely in light of the FBI's investigations of the Mafia. Truman Capote, who helped spread salacious rumors about Hoover, once remarked that he was more interested in making Hoover angry than determining whether the rumors were true.

The attorney Roy Cohn, an associate of Hoover during the 1950s investigations of Communists and known to be a closeted homosexual, opined that Hoover was too frightened of his own sexuality to have anything approaching a normal sexual or romantic relationship.In his 2004 study of the Lavender Scare, the historian David K. Johnson attacked the speculations about Hoover's homosexuality as relying on "the kind of tactics Hoover and the security program he oversaw perfected – guilt by association, rumor, and unverified gossip”. He views Rosenstiel as a liar who was paid for her story, whose "description of Hoover in drag engaging in sex with young blond boys in leather while desecrating the Bible is clearly a homophobic fantasy”.

He views Rosenstiel as a liar who was paid for her story, whose "description of Hoover in drag engaging in sex with young blond boys in leather while desecrating the Bible is clearly a homophobic fantasy”.  He believes only those who have forgotten the virulence of the decades-long campaign against homosexuals in government can believe reports that Hoover appear in compromising situations

He believes only those who have forgotten the virulence of the decades-long campaign against homosexuals in government can believe reports that Hoover appear in compromising situations

Some people associated with Hoover have supported the assertion of his homosexual tendencies.Actress and singer Ethel Merman, who was a friend of Hoover's since 1938, said in a 1978 interview: "Some of my best friends are homosexual. Everybody knew about J. Edgar Hoover, but he was the best chief the FBI ever had”. An FBI agent who had gone on fishing trips with Hoover and Tolson said that the director liked to "sunbathe all day in the nude”. Hoover often frequented New York City's Stork Club. Luisa Stuart, a model who was 18 or 19 at the time, told Summers that she had seen Hoover holding hands with Tolson as they all rode in a limo uptown to the Cotton Club in 1936.

The novelist William Styron told Summers that he once saw Hoover and Tolson in a California beach house, where the director was painting his friend's toenails Harry Hay, founder of the Mattachine Society, one of the first gay rights organizations, said that Hoover and Tolson sat in boxes owned by and used exclusively by gay men at the Del Mar racetrack in California. One medical expert told Summers that Hoover was of "strongly predominant homosexual orientation", while another medical expert categorized him as a "bisexual with failed heterosexuality”.

Hoover was a devoted Freemason, being raised a Master Mason on 9 November 1920, in Federal Lodge No. 1, Washington, DC, just two months before his 26th birthday. During his 52 years with the Masons, he received many medals, awards and decorations. Eventually in 1955, he was coroneted a Thirty-Third Degree Inspector General Honorary in the Southern Scottish Rite Jurisdiction. He was also awarded the Scottish Rite's highest recognition, the Grand Cross of Honor, in 1965. Today a J. Edgar Hoover room exists within the House of the Temple. The room contains many of Hoover's personal papers and records.

To raise money, Cohen was able to tout a cast of Academy Awards winners, such as Jose Ferrer, Celeste Holm and Broderick Crawford, who plays Hoover, and who recently won Best Actor as populist Louisiana demagogue Willie Stark in All the King’s Men. Cohen would get $100,000 one week and spend time on the phone drumming up funds for the following. Going through official channels, Cohen was refused access to government interiors when it was discovered the movie was about the FBI. So he shot on his actors on the fly, telling officials at the Justice Department that they were only taking background shots in order to recreate the locales on a Hollywood soundstage. “We had to wheedle our way in.” Cohen finagled access to Hoover’s own house, where the crew showed up and were greeted by Annie Fields, Hoover’s longtime maid (he left her $3,000 in his will). Ms. Fields “assumed somebody said it was OK so we got away with it. Next thing I know I was in his bedroom looking in his closet.” Cohen contrasts his cavalier mode of shooting Private Files with the “more litigious” climate today. “You shoot a scene in a hotel lobby or somebody’s house, and there’re paintings on the wall, you have to get clearance…you could be sued. It makes movies nightmarishly difficult today.”

Having already been denied official access to government buildings, Cohen says “the only reason we got cooperation on this picture was a real fluke.” Cohen shot scenes at the Mayflower Hotel, where Hoover famously ate dinner each evening with Clyde Tolson, portrayed by actor Dan Dailey. A hotel publicist reported the shoot in the newspaper the next day. While despairing that any media attention would derail the surreptitious production, Cohen received a call from the White House. Betty Ford, the President’s wife, was a former chorus girl and a huge fan of 20th Century Fox musicals like Mother Wore Tights and Give My Regards to Broadway, which starred Betty Grable and…Dan Dailey. Having read Dailey was in town for a movie, the First Lady invited the actor to the White House, where Dailey and Crawford lunched with the Fords, Henry Kissinger and Vice President Nelson Rockefeller. Rockefeller even offered to lend the production use of his limo.

Cohen was not invited to the luncheon, but used the event to his advantage. He called all the government sites where he was previously forbidden, and when he casually let slip that the stars were presently having lunch at the White House, the tone would change. Suddenly, the government PR people were wholly accommodating, and Cohen gained access to such off-limits locales as the FBI training academy in Quantico, VA. In effect, “Dan Dailey saved the picture.” But only ten days before shooting was scheduled to begin, Dailey failed his physical exam (bad heart) and was refused insurance coverage. Cohen didn’t want to tell the actor he was medically incapable, since he “would never get another job if it’s official.” So he went ahead without cast insurance, “even though we had all these old actors” in the movie. “And you know something, if Dan Dailey wasn’t in it, we never would have got invited to the White House, and we never would have got all those locations.”

Cohen painted a less than flattering picture of Rip Torn, who plays FBI agent Dwight Webb. Arriving for rehearsals with the blustery attitude for which the actor is notorious, initially he and Cohen “didn’t hit it off.” “We got into a terrible argument about something,” Cohen recalled, which Torn wanted to “settle with a fist fight in the street.” Perhaps testing Cohen, who claims to have gamely followed the actor outside, Torn relented and said he wanted to do the movie without any problems, and the to men went back to work. Cohen describes Torn as “psychopathic about his hairpiece,” or hairpieces, one for each for the side of his head. “He wouldn’t let the makeup people handle the hair, and hid the pieces in his dressing room, often later forgetting where he hid them.” At one point Torn refused to work, after someone broke into his car and stole his hair, an incident which baffled Cohen. (“Why anyone would steal such a clump of fuzzy stuff?”) So Cohen put a baseball cap on Torn’s head and resumed the shoot.

“No matter what the catastrophe, there was always some way out of it. Whatever situation comes up there’s a way out of it. Some people close down and send everyone home. If you don’t freeze up and don’t give up.”

THE CHIEF FINANCING came from American International Pictures, headed by Sam Arkoff, who made a career producing shoe-string midnight flicks like High School Hellcats and Blacula, and who Cohen “conned into giving up the money.” Arkhoff invested on the belief that J. Edgar Hoover would be played by Rod Steiger, but when Steiger opted to play W. C. Fields in WC Fields & Me, Cohen tried first for Albert Finney, who wasn’t available, then George C Scott, who had not too long ago won an Oscar for his leading role in Patton. Cohen saw a parallel between Direcrot Hoover and General Patton, who was also “widely thought of as an awful person” yet “had such charisma that they transcended the bad feeling about them.” Though Hoover’s severe abuses of justice weren’t exactly state secrets, he still was invited to social affairs like Truman Capote’s Black & White Masquerade Ball in 1966, where the Director hobnobbed in a black mask with Gloria Vanderbilt, Andy Warhol and Sammy Davis Jr. Cohen wasn’t the first bohemian to take an interest in the image of J. Edgar Hoover. The maverick film director Samuel Fuller had once expressed his desire to make a picture about Hoover, whom he thought was “sick, cruel, dogmatic, stupid, racist… everything I like in a character.”

Private Files invents composite characters and provides the motivation behind historically indeterminate episodes, but Cohen abides by his extensive source material. “I read every book that was out about Hoover.” Cohen interviewed top FBI executives and spent time with William Sullivan, at one time Deputy Associate Director (“the number three man in the Bureau”). After a devoted career with the FBI, Sullivan had a falling-out with the Director over the issue of civil rights. In 1970, on a panel before the UPI, Sullivan denied that communists were responsible for race riots and campus violence. Such an idea defied Hoover’s crusade against as black nationalists as subversive rabble-rousers and a threat to domestic security. Sullivan, however, was no radical, and admitted to Cohen that “he was the one who actually wrote the letter to Martin Luther King, Jr. suggesting he commit suicide. He told me he did it. He was proud he did it.”

Cohen explained that Sullivan had hoped to succeed Hoover as Director and sought favor with President Nixon. There was tension between Hoover and Nixon, who ordered the FBI to wiretap a series of government and press figures after a 1969 New York Times article exposed Nixon’s secret bombing campaign in Cambodia. Hoover performed the illegal surveillance, created logs of the recordings, and destroyed the tapes. The logs were not filed with the Bureau’s central records, and were instead entrusted to the D.C. office of William Sullivan. Nixon grew paranoid that Hoover might exploit the wiretap logs. “Hoover was holding that over Nixon.” Sullivan secretly furnished Nixon with the logs, and was forced out of the Bureau after a resulting blowout with Hoover.

The logs, however, never gave much of an advantage to Nixon, who described their contents as “gobs and gobs [of] gossip and bullshitting.” In light of such subterfuge, Sullivan was willing to talk to Larry Cohen, hoping he would come out good and “Hoover and Tolson not as saintly.” In Private Files, Cohen dramatizes these events between Hoover and Nixon, and William Sullivan shows up as fictional character Lionel McCoy, played by Jose Ferrer. But much of Cohen’s primary research was too sensitive to include in the movie, especially the events involving the Watergate scandal. “What we found out, so many of these things, if you put them in the movie the lawyers would jump in, it’ll cause too much trouble.” William Sullivan had told Cohen that W. Mark Felt, who had replaced Sullivan as the number three man in the Bureau, was the mysterious informant Deep Throat. After Hoover’s death, Nixon had appointed L. Patrick Gray as FBI Director, “a lost soul,” who “didn’t know his way around the Bureau at all” and was simply a “functionary of the Nixon administration.” Gray was soon fired after getting caught destroying FBI files for Nixon. Meanwhile, Mark Felt was “really running the entire Bureau,” and when he tipped off journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, says Cohen:

At the time the Watergate story broke, rumors abounded of Felt’s role as Deep Throat, which Felt denied in interviews. Cohen insists that if the FBI, which was “despised,” had been publicly revealed as the leak, the story would not have garnered the sensationalist liberal angle which made Pulitzer Prize-winning heroes of Woodward and Bernstein, who wrote for The Washington Post. The Post was a pro-Kennedy and anti-Nixon newspaper, especially after Nixon’s success in opening China, ending the draft and winning an election “with the highest plurality in modern times.” Cohen claims the Post inflated the Watergate break-in, which was “not a major crime,” and minimized the 1969 Chappaquiddick incident, where Senator Edward Kennedy was behind “a conspiracy that involved killing somebody.” Watergate was “practically a misdemeanor” which “became the biggest hullabaloo in the country,” while ample evidence in Chappaquiddick revealed Kennedy “leaving a girl to die in a car and drown, and getting away with it and moving all the witnesses out of Massachusetts before they could be questioned by the local authorities.” Cohen cites the comparison as “how they can throw the focus from one thing onto another thing.” In Private Files, the character J. Edgar Hoover is shown huffing that “nobody prints anything bad about the Kennedys.”

COHEN TAKES ISSUE with the 1976 movie All the President’s Men. “It’s so dishonest.” The reporters meet Deep Throat in a spooky garage, with footsteps and shadows insinuating that Nixon is tracking them and their lives are in danger. “Never happened!” Cohen insists “they were never in danger, and they never thought they were in danger. That was all bullshit… they put that in the movie to make the picture more dramatic.” The FBI would not have undermined Nixon unless instructed by J. Edgar Hoover. “That’s what my movie said in 1976, but nobody paid any attention to it.”

When asked about how Private Files fits into his oeuvre as a filmmaker, Cohen argues that “there is a semblance of reason behind all these movies.” Cohen finds a pattern of melodrama by “taking symbols of benevolence and turning them into something negative.” He has made movies “about a monster baby [It’s Alive], then ice cream [The Stuff], then an ambulance [The Ambulance], which is supposed to be a vehicle of mercy, but the ambulance is evil.” In a segment for the “Masters of Horror” series on Showtime, Cohen’s script portrays Uncle Sam as a psychopathic killer, as he likewise twists the image of the police in Maniac Cop, written by Cohen. “The FBI fits right into it.” The Bureau was “sold to us for years as perfect guys… straight-shooting American boys,” and was never thought of committing such abuses as ”wiretapping black people or sabotaging the black movement, or whatever… but as American good old-fashion patriots.”

The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover opened at the Kennedy Center in D.C., which was “a terrible mistake.” Because both the Kennedys and Richard Nixon “don’t come off so well” in the movie, neither Democrats nor Republicans reacted positively. “You gotta have one side or the other.” Cohen again cites All the Presidents Men, which was a success because it was conformed to a left-wing agenda and was “definitely pro-Democrat.”

In England, where there was “no ax to grind, the reviews were fabulous, you really thought it was Lawrence of Arabia,” and the movie played a “first run of seven or eight weeks.” Private Files premiered well at The Public Theater in New York, and was hailed as one of the ten best films of the year by Village Voice film critic J. Hoberman. But after dismal distribution, Sam Arkoff pulled the picture and sold it to a tax shelter where the investment could be written off. “From my point of view,” says Cohen, this move “put the picture in profits,” since “they paid for the entire negative cost of the picture, and all the money that came in were profits.” Cohen estimates making “maybe $300,000 or $400,000 off this movie. That’s not bad.”

In 1976, Broderick Crawford hosted Saturday Night Live. “I arranged that,” explains Larry. “In fact I wrote part of that sketch myself.” Cohen had organized a press conference in the ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel to announce the making of the movie. Broderick Crawford showed up in a 1930’s car and hammed-up in the role of Hoover, and the stunt was mentioned in the Sunday Times. Soon SNL producer Jean Doumanian called to invite Crawford as host. During rehearsals, Doumanian contacted Cohen in Los Angeles over problems they were having with Crawford, who “keeps disappearing,” only to be found later drinking in some midtown cocktail lounge. The cast and crew were forced into “babysitting him all day long.” Dan Ackroyd would keep an eye on Crawford for an hour, and then pass the duty to John Belushi, and so on. “You gotta come back” pleaded Doumanian, “and get this guy under control.” Cohen showed up at Studio 8H, maintaining that Crawford will “get you crazy but then when the show goes on the air he’ll know every line of dialogue – you’ll be falling apart but he’ll be cool as a cucumber. Don’t worry about it.” The show included a sketch where Crawford parodies Hoover, but Cohen found it lacking and “rewrote some material.” Because the SNL writers were “very protective” and “would go nuts if someone else wrote for the show,” they credited Jean Doumanian instead with the idea. The sketch ends with Hoover cuddling in bed next to a teddy bear, saying “Goodnight Clyde,” in reference to gay rumors surrounding his intimate relationship with Clyde Tolson. Ultimately, the SNL publicity “didn’t hurt or help us, since the movie wasn’t released until six months later.”

For all these reasons, Private Files quickly fell into obscurity. Though once released on VHS, it was only recently made available on DVD through MGM Archives. The movie screened in 2010 as part of Anthology Film Archives’ “William Lustig Series,” curated by the director of Maniac Cop. This year, interest in the film resurfaced relating to an upcoming Hoover biopic directed by Clint Eastwood and starring Leonardo DiCaprio. DiCaprio’s company, Appian Way, contacted Cohen requesting a copy of Private Files, and provided Cohen with a working script, by Dustin Lance Black, who won an Oscar for Milk. Cohen read the script, spoke briefly with Eastwood’s producing partner, but nothing further materialized.

It might be supposed that J. Edgar Hoover would have approved Dirty Harry to tell his life story. Given Hoover’s supreme vanity and skewed take on reality, the Director might also have been pleased by the choice of clench-browed heartthrob Leonard DiCaprio in the title role. After reading Black’s manuscript, Cohen signed off on a fifteen-page memo that included a lively and provocative rundown of J. Edgar Hoover and the exploitative culture of the FBI, as well as a sustained critique of the script’s distortion and poorly evidences specualtion about Hoover’s alleged homosexuality and cross-dressing habits. “Don’t get me wrong,” Cohen opens, “I’m a great fan of Clint Eastwood’s, and I happen to like the guy…”

Cohen faults the script as a misrepresentation of Hoover both public and private, citing Hoover’s exaggerated role in capturing the kidnapper of “the Lindbergh baby,” as well as scenes of Hoover dressing up in his mother’s clothing after attending her funeral. For Cohen, it is less the subject matter at hand than the corrupting effect on the record of public memory. “The problem,” Cohen argued, “is that whatever Eastwood puts in this movie, that’s what everybody’s going to take as gospel, that will be the history people will accept for the next 50 years.” At a recent dinner with Quentin Tarantino, he told the younger filmmaker that because of Inglourious Basterds “a whole generation of young people will swear to you Hitler was killed in a Paris movie theater by Jewish commandos. Forget about what really happened. Cause they saw it in a movie.” Cohen moralizes that films about history are often a problem because “people don’t like going to movies that make them feel stupid.”

A FANATICALLY PRIVATE man, Hoover nonetheless enjoyed the company of spotlight celebrities like Shirley Temple and Dorothy Lamour, and even went on a few dates with Lelee Rogers, mother of Ginger. But his life-long bachelorhood and puritanical zealousness regarding the bedroom practices of others, whether Martin Luther King Jr. or Eleanor Roosevelt, triggered rampant speculation about his own sex life. Early in his career as FBI Director, Hoover kept the company of young, strapping agents with whom he regularly went to the movies and invited to dine at his home with his mother. But these young bucks were transient companions. In 1928 Hoover recruited Clyde Tolson, a law graduate from Hoover’s alma mater, George Washington University, and described by fellow agents as comporting himself “with icewater in his veins.” Tolson would remain the second in power under Hoover at the FBI until Hoover’s death in 1972. Because Tolson was also Hoover’s sole lifelong personal companion, the dirt-circuit was ripe with word that the twosome were lovers. Yet, besides the rickety allegations set forth in a 1990’s hack biography regarding Hoover giving blowjobs at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel, evidence of the Director’s active sexuality remains speculative. Edgar and Clyde were intimate male friends. Hoover referred to Tolson as “Junior,” while Tolson had affectionately gave Hoover the nickname “Speed.” Sometimes, “Eddie.” Because of Tolson, Hoover was known infamously as “The Boss.”

The documented source of Hoover’s alleged transvestism was Susan Rosenstiel, the ex-wife of millionaire whiskey magnate Lewis Rosenstiel, who was formerly involved in providing substantial funds for the J. Edgar Hoover Foundation, incorporated in 1965 to promote the “American Way of Life.” Cohen describes Mrs. Rosenstiel as a source of scant accountability, “an alcoholic and convicted perjurer” who blamed Hoover for her break-up with Lewis Rosenstiel after Rosenstiel hired Hoover to investigate his wife in support of the couple’s divorce actions. According to Mrs. Rosenstiel, Hoover showed up at a party at the Waldorf-Astoria in women’s dress clothes and was introduced to the guests as “Mary.”

In Private Files, Hoover’s understanding of privacy and justice is depicted less as sexual secrecy than self-loathing. When Ronee Blakely, as Carrie DeWitt, is innocently attracted to young Hoover and moves in for seduction, Hoover is at first shy. “I have to do everything, I understand,” she says, “I don’t mind.” Then Hoover grows suspicious of the girl. His lack of self-esteem bursts forth and instead of returning her advances he accuses her of being a spy. “Who out you up to this!” Hoover cannot believe there would be any other reason for her interest in him. A woman’s seduction is portrayed as deception. The FBI were routinely referred to as “boy scouts,”

“Who out you up to this!” Hoover cannot believe there would be any other reason for her interest in him. A woman’s seduction is portrayed as deception. The FBI were routinely referred to as “boy scouts,” and Hoover’s self-image is of a lone little boy afraid and intimidated by the girls. The same thing often recurred in the short stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald, but these boys never ended up spying on Hollywood communists and persecuting civil rights leaders.

and Hoover’s self-image is of a lone little boy afraid and intimidated by the girls. The same thing often recurred in the short stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald, but these boys never ended up spying on Hollywood communists and persecuting civil rights leaders.

Later in the movie, Hoover discovers Ms. DeWitt has died, and he sits alone at his table at the Stork Club, a schmancy hangout for mobsters and showgirls and gossip-page yammerheads. Hoover is melancholy, and served drinks by his favorite waiter. After casually confiding to the waiter that he knows the man’s daughter belongs to a Communist club, and that his son’s girlfriend is pregnant, Hoover recites his favorite poem, Rudyard Kipling’s “If.” Cohen says it was the poem Hoover always recited to his mother as a boy.

J Edgar Hoover was one of the worst people ever to have risen to power in the United States. He made the FBI into something approximating a secret police. He is responsible for a lot of the hysteria surrounding leftist political movements in the 20's, 30's 40's, 50's and 60's, linking them with communism. The Mafia had photographic evidence of Hoover in drag. He slept in the same bed with Clyde Tolson, his constant companion. The Mafia threatened to expose him if he didn't leave them alone, so Hoover turned to hunting down communists and the mafia flourished from the end of WWII to the Kennedy administration when RFK launched some 95 inverstigations into Mafia activities. And he had racketeering statutes to make his investigations a real threat to the Mafia bosses, men in their 50's or older. Conviction would mean a life sentence. We know what happened to the Kennedys. Hoover, Hoover... a first class son of a bitch.

Hoover had enemies such as the KKK, communists, nazis, mobsters and general liberals. That is why there has been so many lies against him.

One man made the G-men legendary, turned a bumbling FBI into what was perceived to be an army of truth and justice known the world over, and made himself a towering American legend: J. Edgar Hoover.

Of course today, the Hoover legend is not just about crime fighting. It has as much to do with playing fast and loose with civil liberties,

above Exploitation auteur Larry Cohen’s unjustly forgotten labor-of-love biopic gets resurrected again this year, in honor of the release of Clint Eastwood’s Leo-for-the-Oscar! vehicle.

That organization included the introduction of fingerprint files, crime labs, and of course there were the agents themselves. Hoover insisted they be educated, dedicated to their job, and

He created a mystique about himself that the people would not allow him to leave.Hoover's mystique came from a mastery of modern public relations long before official Washington even knew what that was.

He created a mystique about himself that the people would not allow him to leave.Hoover's mystique came from a mastery of modern public relations long before official Washington even knew what that was. Hoover brought Madison Avenue to Pennsylvania Avenue. Hoover ran the FBI, but he managed its image everywhere,

Hoover brought Madison Avenue to Pennsylvania Avenue. Hoover ran the FBI, but he managed its image everywhere,  He looked at every movie, every reference, every scene, every actor. He approved it all. And he did. In the ‘FBI Story’ that starred Jimmy Stewart, he cleared Jimmy Stewart for instance. He interviewed him, gave his okay.And then there was James Cagney.

He looked at every movie, every reference, every scene, every actor. He approved it all. And he did. In the ‘FBI Story’ that starred Jimmy Stewart, he cleared Jimmy Stewart for instance. He interviewed him, gave his okay.And then there was James Cagney.Hoover felt insulted by the civil rights leader. King dared to ignore a Hoover phone call.From that one unanswered phone call, the rest of King's life, Dr. King did not have a free moment from the specter of J. Edgar Hoover, ever.

He tapped him, he followed him.Hoover collected intimate details on King's private life, details that would haunt and embarrass King's family for years to come. Hoover in some sense was jealous of Martin Luther King.

He tapped him, he followed him.Hoover collected intimate details on King's private life, details that would haunt and embarrass King's family for years to come. Hoover in some sense was jealous of Martin Luther King.He had a wife, he had a family, he had authority, he had respect. He had everything and Hoover was definitely jealous.

Robert Kennedy made Hoover turn his attention away from fighting communism to organized crime, which Hoover, at that time, believed was much less of a threat.

Hoover's career nearly came to an end with Kennedy but He didn't fire Hoover because he didn't know what Hoover really knew. The same reason no one else fired Hoover. When it really came down to it.When it came to the Kennedy clan, Hoover perhaps felt the most contempt for Attorney General Robert Kennedy.He considered him an outrage. He thought he was a loose cannon he could not control and he loved being in control.He had nudes of many people. There was an obscene file that he kept himself.”

He was interested in pornography.

he was definitely interested in pornography. He would say from an intellectual standpoint of course to know what was out there so he could fight it.

And whose nude pictures did Hoover have ,Well, Marilyn Monroe, perhaps no big surprise, but there was also another.

Eleanor Roosevelt

HOW does one go about getting and why would one even want naked pictures of Eleanor Roosevelt?

W.C. Fields happened to have a set of pictures, what was purported to be Eleanor Roosevelt. I have not seen these myself because they were subsequently destroyed

Suits of the 1920s and 1930s are marked a bit by excess. Throughout the 1920s pant legs grow steadily in width. The widest pants were worn by students at Oxford College to conceal their knickers while attending classes. Oxford Bags could be up to 32 inches in width. While most men never wore this fad, trousers became fuller through their influence. Pant legs narrow slightly during the 1930s, but as seen in the images to the right, hem lengths are still on the wider side. A 1930s innovation was the addition of a zipper in the trouser fly. First worn by the youthful Prince of Wales (AKA the Duke of Windsor), popular fashion quickly jumped on the bandwagon.

By the 1930s even the torso of the jackets are cut with extra boxiness for added comfort. When these coats were buttoned the extra fullness fell softly with a slight drape or wrinkle through the chest and shoulders. Referred to as the English Drape Suit, this style is the prominent suit cut of the 1930s. Shoulder padding also becomes sharper and wider during these decades.

A typical man's suit consisted of a jacket, vest, and two pair of trousers. All of the pieces were tailored out of the same fabric. Sack suits remained the basis of a man's wardrobe. However as we move toward the war years, they become increasingly confined to work in offices, going to church, and formal/fancy occasions. White suits for summer were available for those who could afford variety in their wardrobe. As a result, the white linen or flannel suit became symbolic of an upper-class life style.

. But Hoover had heard the story and asked W.C. Fields to see the pictures and W.C. Fields sent him the pictures. And there in lies the power and play of the man

The oddity in Hoover's collection of secrets is perhaps the key to his power. In Washington Hoover himself was an oddity, receiving special treatment wherever he went.He had things no one else could have, knew things no one else could know. For him ordinary rules did not apply. Until the end, Hoover actually believed he was America's ultimate protector, something America believed for awhile.Will there ever be another J. Edgar Hoover? Of course , America is based on people like Hoover, Cross dreesers not only but traitors .In Schaumburg, Illinois,

a grade school was named after Hoover. In 1994, after personal information about Hoover was released, the school's name was changed to reflect Herbert Hoover instead of J. Edgar Hoover.

death in 1972 at age 77. Hoover is credited with building the FBI into a large and efficient crime-fighting agency, and with instituting a

death in 1972 at age 77. Hoover is credited with building the FBI into a large and efficient crime-fighting agency, and with instituting a Late in life and after his death Hoover became a controversial figure, as evidence of his secretive

The szuit worn by the man who shot Dillinger

The szuit worn by the man who shot DillingerHoover transformed the FBI into his private secret police force; Truman stated that "we want no Gestapo or secret police. FBI is tending in that direction.

above the man Dillinger killed by another man sent by Hoover a shadow |

Two siblings had certificates. Hoover's was not filed until 1938, when he was 43.

Two siblings had certificates. Hoover's was not filed until 1938, when he was 43.Hoover grew up near the Eastern Market

He obtained a law degree from George Washington University Law School in 1916 where he was a member of the Alpha Nu Chapter of the Kappa Alpha Order and an LL.M., a Master of Laws degree, in 1917 from the same university.

While a law student, Hoover became interested in the career of Anthony Comstock,

While a law student, Hoover became interested in the career of Anthony Comstock,Hoover lived in Washington, D.C., for his entire life.

, authorized by President Wilson at the beginning of World War I to arrest and jail disloyal foreigners

, authorized by President Wilson at the beginning of World War I to arrest and jail disloyal foreigners In August 1919,

Hoover became head of the Bureau of Investigation's new General Intelligence Division—also known as the Radical Division because its goal was to monitor and disrupt the work of domestic radicals.

Hoover became head of the Bureau of Investigation's new General Intelligence Division—also known as the Radical Division because its goal was to monitor and disrupt the work of domestic radicals.America's First Red Scare was beginning, and one of Hoover's first assignments was to carry out the Palmer Raids.

The Palmer Raids were attempts by the United States Department of Justice to arrest and deport radical leftists, especially anarchists, from the United States.

The raids and arrests occurred in November 1919 and January

Hoover and his chosen assistant, George Ruch monitored a variety of U.S. radicals with the intent to punish, arrest, or deport them. Targets during this period included Marcus Garvey

In 1921, he rose in the Bureau of Investigation to deputy head, and in 1924, the Attorney General made him the acting director. On May 10, 1924,

Hoover was noted as sometimes being capricious in his leadership; he frequently fired FBI agents, singling out those who he thought "looked stupid like truck drivers"

Hoover often hailed local law-enforcement officers around the country and built up a national network of supporters and admirers in the process. One that he often commended was the conservative sheriff of Caddo Parish

.

who became famous for leaping over bank cages and repeatedly escaping from jails and police traps, frequently made newspaper headlines across the United States.

who became famous for leaping over bank cages and repeatedly escaping from jails and police traps, frequently made newspaper headlines across the United States.In the same period, there were numerous Mafia shootings as a result of Prohibition, while Hoover continued

to deny the very existence of organized crime. Frank Costello helped encourage this view by feeding Hoover, "an inveterate horseplayer" known to send Special Agents to place $100 bets for him, tips on sure winners through their mutual friend, gossip columnist Walter