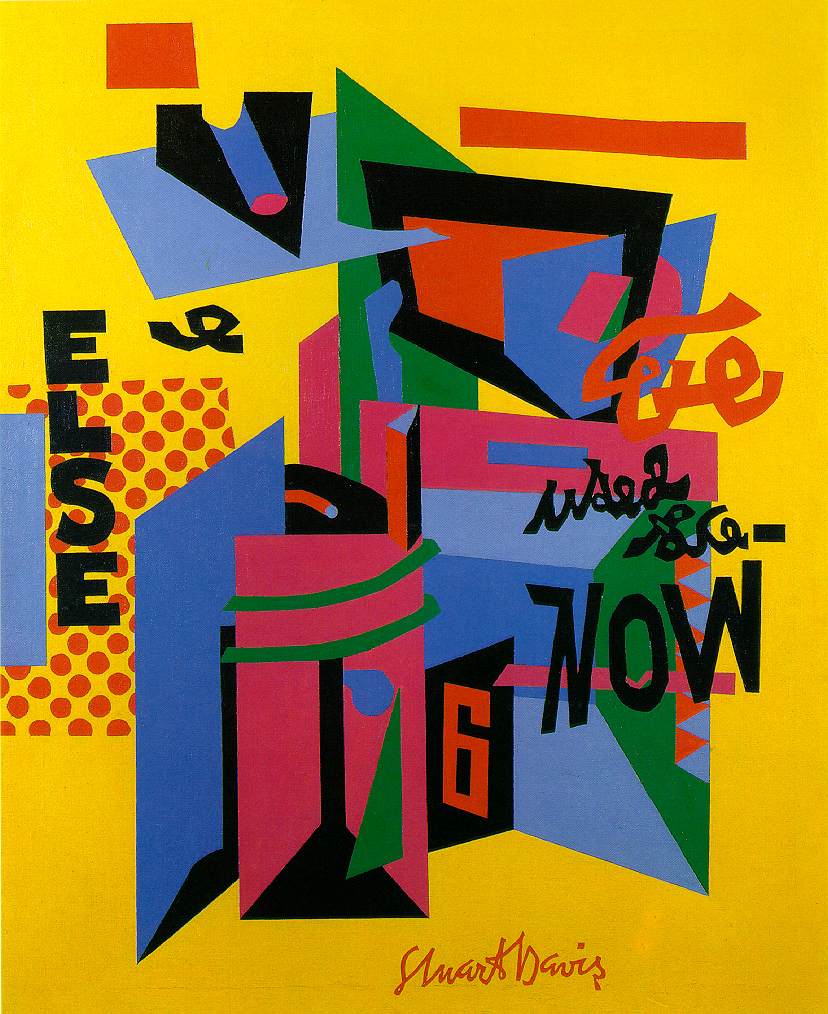

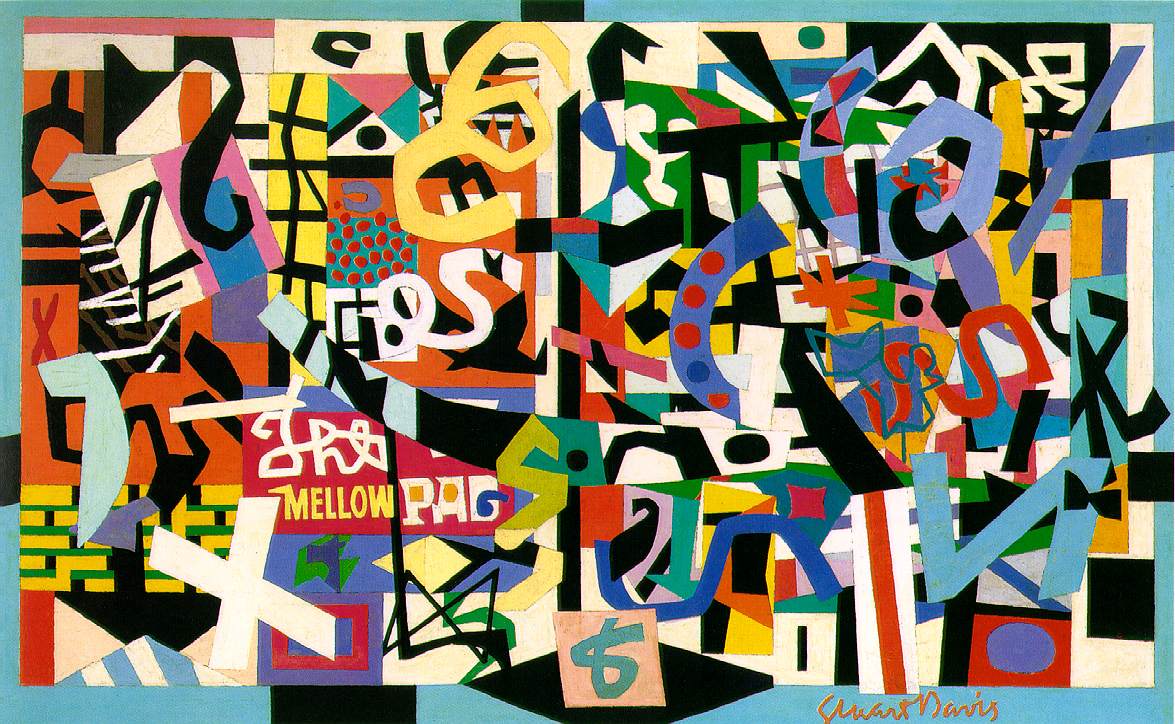

Stuart Davis (December 7, 1892–June 24, 1964), was an early American modernist painter. He was well known for his jazz-influenced, proto pop art paintings of the 1940s and 1950s,

Stuart Davis (December 7, 1892–June 24, 1964), was an early American modernist painter. He was well known for his jazz-influenced, proto pop art paintings of the 1940s and 1950s, bold, brash, and colorful, as well as his Ashcan School pictures in the early years of the 20th century. With the belief that his work could influence the sociopolitical environment of America,

bold, brash, and colorful, as well as his Ashcan School pictures in the early years of the 20th century. With the belief that his work could influence the sociopolitical environment of America, Davis’ political message was apparent in all of his pieces from the most abstract to the clearest.[1] Contrary to most modernist artists, Davis was aware of his political objectives and allegiances and did not waver in loyalty via artwork during the course of his career.[2] By the 1930s, Davis was already a famous American painter, but that did not save him from feeling the negative affects of the Great Depression. No one was exempt from the effects of the Great Depression and led to Stuart Davis being one of the first artists to apply for the Federal Art Project. Under the project, Davis created some seemingly Marxist works; however, Davis was too much of an independent person and thinker to fully support Marxist ideals and philosophies.[2] Despite several works that appear to be nondemocratic or push Marxist views, Davis’ roots in American optimism is apparent throughout his lifetime

Davis’ political message was apparent in all of his pieces from the most abstract to the clearest.[1] Contrary to most modernist artists, Davis was aware of his political objectives and allegiances and did not waver in loyalty via artwork during the course of his career.[2] By the 1930s, Davis was already a famous American painter, but that did not save him from feeling the negative affects of the Great Depression. No one was exempt from the effects of the Great Depression and led to Stuart Davis being one of the first artists to apply for the Federal Art Project. Under the project, Davis created some seemingly Marxist works; however, Davis was too much of an independent person and thinker to fully support Marxist ideals and philosophies.[2] Despite several works that appear to be nondemocratic or push Marxist views, Davis’ roots in American optimism is apparent throughout his lifetimeStuart Davis was born on December 7, 1892, in Philadelphia to Edward Wyatt Davis, art editor of the Philadelphia Press, and Helen Stuart Davis, sculptor.[3] Starting in 1909, Davis begun his formal art training under Robert Henri, the leader of the Ashcan School, at the Robert Henri School of Art in New York under 1912.[3][4] During this time, Davis befriended painters John Sloan, Glenn Coleman and Henry Glintenkamp.[5]

In 1913, Davis was one of the youngest painters to exhibit in the Armory Show, where he displayed five watercolor paintings in the Ashcan school style.[6][7] In the show, Davis was exposed to the works of a number of artists including Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. Davis became a committed "modern" artist and a major exponent of cubism and modernism in America.[6] He spent summers painting in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and made painting trips to Havana in 1918 and New Mexico in 1923.[6]

In the 1920s he began his development into his mature style; painting abstract still lifes and landscapes. His use of contemporary subject matter such as cigarette packages and spark plug advertisements suggests a proto-Pop art element to his work.[8]

In 1928, he visited Paris, France, where he painted street scenes. In the 1930s, he became increasingly politically engaged; according to Cécile Whiting, Davis' goal was to "reconcile abstract art with Marxism and modern industrial society".[6] In 1934 he joined the Artists' Union; he was later elected its President.[6] In 1936 the American Artists' Congress elected him National Secretary. He painted murals for Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration that are influenced by his love of jazz.[6]

In 1938 Davis married Roselle Springer and spent his late life teaching at the New York School for Social Research and at Yale University.[3]

He was represented by Edith Gregor Halpert at the Downtown Gallery in New York City.

Davis died of a stroke in New York on June 24, 1964, aged 71.

Davis’ interactions with European modernist works in 1913 had a significant impact on his growth as an artist. The realist Robert Henri had trained Davis to paint in a realist fashion since Davis’ youth, however Davis’ excursion with European modernist caused him to raise the modernist flag instead. Stuart Davis did not switch to modernism out of spite for Henri, but rather out of appreciation for the many forms of art that exist. The love and adoption of European modernism morphed into political and social isolationism that was a staple of American in the 1920s and 1930s. Davis never joined an art group during the 1920s and became the sole author of Cubism which used abstract colors and shapes to show various dynamics of the American cultural and political environment. From 1915 to 1919, Davis spent summers in Massachusetts where his art work had intense color pallets paired with simple designs, trademarks of several artists that Davis admired at the Armory Show.[2] The early 1920s saw many American artist abandon modern art, but Davis continued to try to discover ways to implement his knowledge of shapes and colors into his art work. By the end of the 1920s, Davis was done more work and research into Cubism and its various levels of sophistication than any other American artist at the time.[2] During the 1930s and 1940s, Davis attempted to make is work with Cubism altered and more original. While working on several murals for the Federal Art Project, Davis tried to find alternatives to traditional Cubist structure. The emergence of Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s made some question whether Davis was still the greatest modernist in the country, however, this test did not shake his resolve as he continued to develop his own painting style.

Davis was first professionally trained by Robert Henri, who was an American realist. Henri began teaching Davis in 1909. Henri did not look highly upon American art institutions at the time, which led to him joining John Sloan and six other anti-institutional artists (known as “the Eight”) to put on an exhibit at the Macbeth Gallery in 1908. Through his vocal rejection of academic norms in painting, Henri encouraged Davis and his other students to find new forms and ways to express their art and to draw on their daily lives for inspiration.

Davis was born during the Progressive Era, a time when America had a growing sense of optimism about itself as a nation through its technologies and management in the material and social realm. Through this, Davis had a great sense of pride in being American and led to him creating several works centered around a “Great America.” After his training from Henri, Davis would walk around the streets of New York City for inspiration for his works. His time amongst the public caused him to develop a strong social conscience which was strengthened through his friendship with John Sloan, another anti-institutional artist. Additionally, Davis frequented the 1913 Armory Show (in which he exhibited his work), to further educate himself on modernism and its evolving trends. Davis acquired an appreciation and knowledge on how to implement the formal and color advancements of European modernism, something Henri did not focus on, to his art.[2] In 1925, the Société Anonyme put on an exhibit in New York with several pieces by the French artist Fernand Léger. Davis had a large amount of respect for Léger because like Davis, Léger sought the utmost formal clarity in his work. Davis also appreciated Léger’s work for the subject matter: storefronts, billboard and other man-made objects. In the early 1930s after returning from a trip to Europe to visit several art studios, Davis was re-energized in his identity in his specific work. Previously, he saw Europe as a place bursting at the seams with talented artists, but now he felt as if he was of the same caliber if not greater than his European counterparts. According to Davis, his trip “allowed me to observe the enormous vitality of the American atmosphere as compared to Europe and made me regard the necessity of working in New York as a positive advantage.”

“The act of painting is not a duplication of experience, but the extension experience on the plane of formal invention.”

“[Modern art] is a reflection of the positive progressive fact of modern industrial technology.”

“I don't want people to copy Matisse or Picasso, although it is entirely proper to admit their influence. I don't make paintings like theirs. I make paintings like mine.”

No comments:

Post a Comment